This article is more than 1 year old

Ofcom: 4G won't knock out granny's personal alarm

LTE's lack of power and spectral capacity will save her

Ofcom has been looking at how 4G networks will interfere with the short-range devices next door, and concludes that LTE handsets haven't the power or capacity to generate significant interference.

According to the study carried out by the regulator (PDF, surprisingly readable) LTE devices are too conscientious in their power consumption, and the bands will be too crowded with other users, for the full potential of LTE transmission to be unleashed, thus mitigating the interference risk almost entirely.

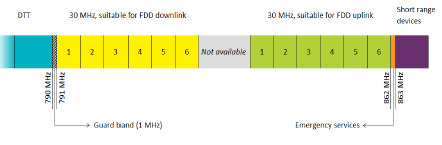

When the 800MHz blocks are sold off next year as part of the 4G auctions, one of the uplink bands (handset to base station) will be right beside the spectrum reserved for short-range devices. These devices include unlicensed wireless microphones, personal alarms and amplified headphones for the hard of hearing, and concerns have been raised that LTE handsets could knock out those users – concerns Ofcom would like to put to rest.

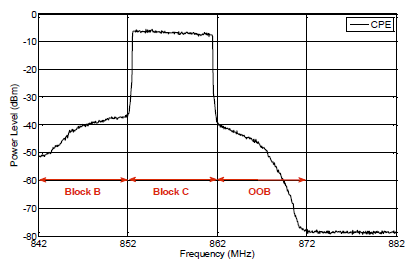

We talk about radio transmission existing within a band – 853-862MHz in this specific instance – but signals aren't as square as we'd like and leak into neighbouring bands in what's often described as a bell shape. That leakage is known as "out of band", or OOB, but as Ofcom's work shows, the device manufacturers have done sterling work squaring the signal for LTE.

Less of a bell, more of a ... erm ...

This shows the signal from an LTE device operating between 852 and 862MHz, which is where the only live network available for testing was running, but Ofcom has extrapolated that data to work out how a network in the upper band would operate - particularly important as that upper band is the one which comes with a national-coverage requirement.

Mobile phones don't transmit at full power all the time, in fact they very rarely rack up the watts in the interest of saving battery life. Both the handset and the base station measure each other's signals and let each other know when it's OK to reduce the power, which is almost all the time. Phones also don't transmit continuously, as mobile telephony is time-sliced as well as code-divided, so each user only transmits at specific moments in time (again to save battery life), further reducing the potential for interference.

The emergency users directly above the 4G band are already being cleared out, so it’s the audio devices running from 863 to 865MHz which are most at risk. That includes low-end wireless mics such as one might pick up in Maplin or similar, which would amplify any interference. Above 865MHz are RFID tags, very short range but reliant on sensitive receivers, while above that are some smart meters and grannies pendant with the red button in case she falls.

Ofcom's work assumes the bands are filled with LTE signals, and that the upper portion is only used for the uplink (handset to base station) which is unlikely to be filled to capacity. Any network hoping for international roaming will need to follow that plan, so it’s a fair assumption, though the licences are technology-neutral.

So it seems that 4G won't knock out the neighbours, but as we pack ever more signals into the overcrowded radio spectrum, dealing with noisy neighbours is going to become increasingly important. We should expect to see a lot more work of this kind in the next few years. ®