This article is more than 1 year old

Canadian cyborg says Google Glass design is cracked

Bad choices could 'set the movement back years'

Wearable computing pioneer and self-proclaimed "cyborg" Steve Mann says it's fine that Google is popularizing wearable technology with its Project Glass, but he's concerned that the online giant may be making serious mistakes with its design.

"I have mixed feelings about the latest developments," Mann writes in the March issue of IEEE Spectrum. "On one hand, it's immensely satisfying to see that the wider world now values wearable computer technology. On the other hand, I worry that Google and certain other companies are neglecting some important lessons."

Mann first began experimenting with wearable tech in the late 1970s, and has continued his pursuits as a professor with the University of Toronto's Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering.

He's a daily user of what he calls "computer-mediated reality" systems, going as far as to have a custom-built set of computerized spectacles permanently attached to his head – a fact that caused him some trouble at a Parisian McDonald's restaurant last year.

That makes him something of an expert on wearable computers, how humans react to them, and how they interact with them. And he says he sees Google making some very familiar blunders – ones that could even end up doing the wearable computing movement more harm than good.

For one thing, he says, there's no getting around the fact that your eyes see things differently when you're wearing a computerized headset like Google Glass. And while it's not much trouble for your brain to adjust to new visual inputs, the problems come later, when you take the glasses off.

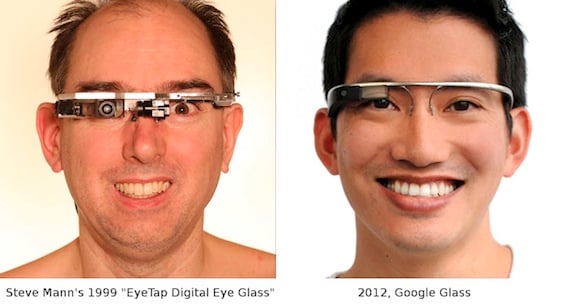

One of these men is a model*. The other is an expert in wearable computing. Can you tell which is which?

"Through experimentation, I've found that the required readjustment period is, strangely, shorter when my brain has adapted to a dramatic distortion, say, reversing things from left to right or turning them upside down," Mann says. "When the distortion is subtle – a slightly offset viewpoint, for example – it takes less time to adapt but longer to recover."

What's more, Mann says that projecting unaccustomed imagery into the eye can have disorienting effects – particularly in the case of full-motion video.

"Virtual-reality researchers have long struggled to eliminate effects that distort the brain's normal processing of visual information, and when these effects arise in equipment that augments or mediates the real world, they can be that much more disturbing," he explains.

Mann says the design of Google Glass, in which the display is positioned over only one eye, can cause problems, too. Because the human eye cannot focus on something that's so close, Glass and similar designs use fixed-focus lenses to make the display seem further away than it is. But that forces each eye to focus on a different plane, which Mann says can cause severe eyestrain.

In the worst case, Mann says, long-term use of such devices could actually damage users' eyesight – particularly in the case of young children, and particularly if the devices are misconfigured.

Mann says his own, more recent wearable computer designs use optics to ensure that the device's camera captures imagery from the exact same perspective as the eye does, and they position the computer display directly ahead of the user, rather than off to one side. Still other optical tricks allow the wearer to view the display while focusing at any distance.

Solving problems like these will be just as important to the future of wearable computing as addressing issues around privacy and surveillance, Mann says.

"It's astounding to me that Google and other companies ... haven't leapfrogged over my best design (something I call 'EyeTap Generation-4 Glass') to produce models that are even better," Mann writes. "Perhaps it's because no one else working on this sort of thing has spent years walking around with one eye that's a camera. Or maybe this is just another example of not-invented-here syndrome." ®

* Actually, the smart-looking bloke is Stephen Lau, a Google engineer.