This article is more than 1 year old

Doctor Who nicked my plot and all I got was a mention in this lousy feature

How writers plundered sci-fi, literature, films and more

Doctor Who @ 50 There’s no question: blocked Doctor Who writers and Script Editors - or Story Editors as they were in the very early days - frequently turned to movies and books for inspiration. They regularly resorted to, ahem, "borrowing" plots and ideas from famous flicks and notorious novels for the basis for their Doctor Who stories.

Sherlock Holmes and the Butcher of Brisbane: ”Perhaps you’ve read my monograph on the many varieties of Chinese bath soap?”

Source: BBC

Heck, the show itself was brought into being on the back of H G Wells’ The Time Machine and the works of Jules Verne, and later contributors were no less keen to plunder the lands of science fiction, literature and mythology in order to meet script deadlines.

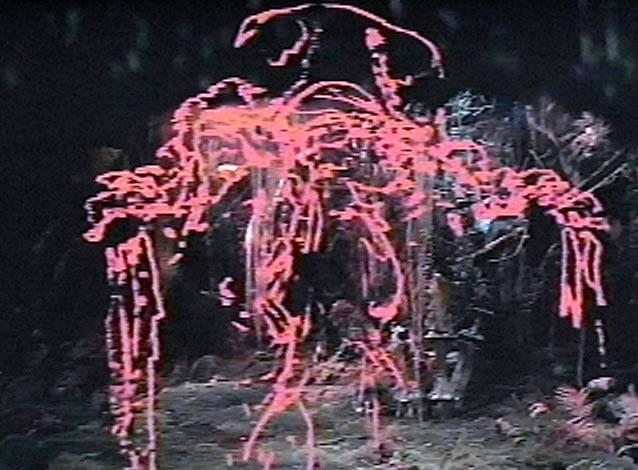

Often the designers and special effects guys went along too, taking visual cues from the source. Consider the invisible-then-red-outline anti-matter beast that attacks Tom Baker in 1974’s Planet of Evil in almost direct imitation of the invisible-then-red-outline Monster of the Id that attacks Leslie Nielsen in 1956 film Forbidden Planet. The villain in both is an unhinged scientist; the protagonists in both cases are crews of military starships. Planet of Evil, written by Louis Marks, lacks the vast city of the Krell but makes up for it with one of the best-realised alien jungle sets in television sci-fi history.

And all that’s before you remember the other half of the story is a futuristic take on The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, with Freddie Jaeger’s Professor Sorenson mutating in a moment from tired anti-matter boffin to the shaggy beast within. A nice twist: here the Prof takes an archetypical smoking medicinal draught to prevent the transmogrification rather than trigger it.

From the Forbidden Planet of Evil: a red, semi-visible monster

Source: BBC

In the years before home video players, it was easier to get away with this kind of thing, of course. But now writers’ plundering is exposed for all to see. Here, then, are some of the more egregious examples.

Writer Robert Holmes was perhaps the most shameless of Doctor Who’s rip-off merchants. Many of his stories appear in our list, and a few of the others were commissioned and heavily rewritten by him during his time as the programme’s Script Editor in the mid-1970s. That said, it’s surely no coincidence that Holmes was also one of the best Doctor Who writers to contribute to the show’s initial 25-year run and possibly, some would argue, the best writer the classic series ever had.

Holmes’ secret was to grab the essence of his source material but cleverly wrap it enough new stuff that the story that followed felt totally Doctor Who. Yes, you might recognise a character, a situation, a milieu or an entire genre from one of his stories, but the revelation wouldn’t kill the adventure stone dead. Rather than making it suddenly impossible for the viewer to willingly suspend his or her disbelief, Holmes’ borrowings and the way they were woven into the script actually made the story more enjoyable.

‘The World shall hear from me again. Not Fu Manchu but mad magician Li-Hsen Chang. And Mr Sin

Source: BBC

Take The Talons of Weng-Chiang, Holmes’ distillation of so much cod Victoriana. It’s primarily flavoured with allusions to Sherlock Holmes, though he character as it existed in the popular imagination rather than Conan Doyle’s creation. Likewise popular culture impressions of Jack the Ripper and the fog-bound pea-souper London of Ripper mythology. There’s a hint of Edgar Allen Poe in there too and a soupçon of Bram Stoker. There’s even a comical nod to popular 1970s variety show The Good Old Days.

And not just Leonard Sachs, but Sax Rohmer. You might detect in Talons a whiff of Rohmer’s Chinese fiend Fu Manchu, who surely inspired Robert Holmes’ Oriental magician Li-Hsen Chang and his gang of Chinese martial artist henchmench, the Tong of the Black Scorpion. Rohmer’s tales derive from the early 20th Century rather than the nineteenth. So does villain Magnus Greel’s subterranean lair. Located beneath a theatre and served with sewer highways and byways, it comes straight out of Gaston Leroux’s 1909 novel The Phantom of the Opera.

A more recent steal: the 1974 movie version of Ian Fleming’s The Man with the Golden Gun features a giant laser gun and a fight with a midget, here represented by the Dragon Ray Gun and Mr Sin, the ”pig-brained Peking Homonculous” - played, as all characters of diminutive stature were back then, by Deep Roy, better known to cinema goers as Princess Aura’s pet in Flash Gordon and every single Umpa Lumpas in Tim Burton’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

The Linx effect: Sontaran kidnaps Earth boffins... just like Exeter the Metallunian does in This Island Earth

Source: BBC

Holmes made a habit of this kind of thing. The Time Warrior, Holmes’ story that introduced the Doctor Who audience to the Sontarans, then a harsher, more brutal race of clone warriors than the comedy martinets of today, lifts one of its central premises - alien kidnaps Earth scientists to make use of their brain power - from 1957 sci-fi flick This Island Earth, though Holmes made the abduction happen through time rather than across space, and passes water on the source material from a great height with his trademark deadpan dialogue: “So you have a primary and secondary reproductive system. It is inefficient. You should change it.”