This article is more than 1 year old

NASA: checking out the sun in Stereo

New solar observatory ready for August launch

Next month, NASA is to launch a new solar observatory that will make it possible for scientists to observe the sun in three dimensions for the first time. This should lead to better forecasting of space weather and a clearer understanding of the processes at work in our local star.

The Stereo mission (Solar TErrestrial RElations Observatory) is composed of two near-identical space craft with a battery of detectors on each. They will record data in Ultra Violet, and will also use a coronagraph, which creates an artificial eclipse, to study the outer atmosphere of the sun.

They will both be launched into solar orbits, but set in different directions so they gradually drift further and further apart, sending back data on solar activity from two angles at once.

Currently, even using the SOHO observatory we can only really see the sun from the Earth's point of view, which gives scientists a pretty one dimensional picture of our star. It gives us great images of material being ejected from the solar limb (the side of the sun) but it is still impossible to tell whether or not ejections are heading towards or away from the Earth until the material hits SOHO itself. This gives us just an hour's notice.

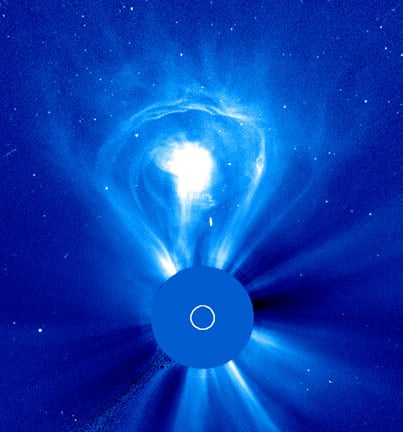

Stereo will allow scientists to make observations of the sun from side on, so they can better track material from coronal mass ejections (CMEs) as it is flung into space.

The progress of the CMEs will be monitored by a groundbreaking new device called a Heliospheric Imager, built at Birmingham University in the UK. It tracks the material using only the sunlight reflected from the plasma particles. This light is so much fainter than the solar glare that the detector has specially designed "baffles" that reject the stray light and allow it to pick out the solar storms.

The observatories should give us more warning when this solar material is heading our way: up to two and a half days. This is good news for satellite owners, power companies and mobile phone operators, as big CMEs can disrupt all of these, as well as forming the Auroras Borealis and Australis.

To coordinate the cameras over the roughly 500,000km separation, mission scientists will have to take the speed of light into account. This means that the two craft will take their snapshots at different times, in order to record the same event.

The mission is nominally expected to last for two and a half years, but could go for as long as four years. At this point, the two craft will be on opposite sides of the sun from each other and Earth will only be able to receive data from one of the satellites at that point. The distances involved also mean data will take longer and longer to get through as the mission progresses.

The craft was originally scheduled to launch on 1 August. However, a series of small problems meant that the date was becoming unrealistic. Last week, a problem with a crane meant that loading the rocket took longer than expected. Then, this week, engineers spotted a small leak in the rocket's fuel tank.

"It isn't anything serious, and has probably already been fixed," a spokeswoman told us. "But it meant things would have been rushed, so they moved things to the next launch window."

Barring any further "small problems", the rocket will now lift off sometime between 20 August 20 and 6 September. ®