This article is more than 1 year old

Shell pulls out of Thames Estuary mega-windfarm

Project could supply a thousandth of UK's energy

Oil giant Shell has pulled out of the world's biggest windfarm project, in a move which has cast doubt over the scheme's future.

The £2bn London Array, intended to be built in the Thames Estuary, will need to find a new backer in order to proceed.

For the London Array Project, Shell was partnered with UK power operator E.ON and Dong Energy, the firm behind much of the substantial Danish windpower base. E.ON chief Paul Golby has suggested that Shell's pullout could torpedo the scheme.

"Shell has introduced a new element of risk into the project which will need to be assessed," he told the Guardian.

"The current economics of the project are marginal at best," he added, citing steel costs and supply bottlenecks - and this despite the fact the UK government renewable energy quota system is currently said to be offering a bonanza for windpower operators.

(However, it has long been suggested that the current subsidy system is biased in favour of onshore wind as opposed to offshore.)

Offshore windfarm projects like the Array are thought by renewables advocates to be the main answer to the UK's energy needs. They could allow the construction of taller windmills than would be practical ashore; and would potentially be able to reap the benefit of more predictable winds, less affected by terrain and surface phenomena.

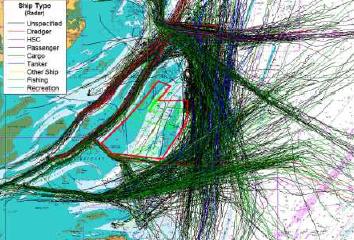

The London Array would be the biggest ever, filling the channel in the outer Thames Estuary between the Kentish Knock and Long Sands banks with up to 341 turbines. This is one of the few areas of the estuary where it wouldn't be in the middle of a heavily used shipping lane, though looking at typical vessel movement in the immediate area you'd have to say there's still some risk of collisions.

The Array site shown in red on a plot of shipping movements.

According to the Array website:

When fully operational, it would make a substantial contribution to the UK Government’s renewable energy target of providing 10 per cent of the UK’s electricity from renewable sources by 2010... it is expected that the project would represent nearly 10 per cent of this target.[The Array] would generate up to 1,000 MW of electricity ...

In summary, then, the entire Array would generate one per cent of the UK's electricity. Windfarm planners like to describe their capacity in terms of maximum possible output, assuming all turbines spinning at best speed - this is the 1,000 megawatts referred to above.

In reality, the wind is seldom blowing at just the right speed. Sometimes the turbines stop altogether, due to flat calms or strong gales; mostly they run at much less than max output.

According to this pdf (page 3) from the Array, on average the project would put out 3,100 gigawatt-hours per annum, equating to average output of 354 megawatts rather than 1,000.

Is that one per cent of the UK's leccy? Not quite. The government says Blighty used 351.4 terawatt-hours in 2006, or 351,400 gigawatt-hours. The London Array at full poke could have delivered 0.88 per cent of that; on current trends, by the time it's built you'd be looking at 0.77 or so.

Still, it sounds better to say "we will deliver nearly 10 per cent of the government's target" than "we will deliver a fraction of a percentage point of the UK's electricity".

And electricity is just one of the ways we use energy. There's also transport fuel, gas, heating oil, etc. The UK actually used a total of 2,700 terawatt hours of energy in 2006. (Full gov details in pdf here. The conversions between tons of oil and gigawatt-hours are at the back.)

That's a ballpark figure for how much we'd need in order to switch to electric or hydrogen transport, stop using gas heating, to generally stop emitting carbon and be ready for the inevitable post-fossil-energy future.

(That is, stop emitting carbon due to energy usage. We and the cows would still be puffing away, though presumably that would be OK. And all this assumes that the spikes and troughs in renewables output are being dealt with by millions of plugged-in electric car batteries or something.)

In other words, the mighty London Array, fully operational, would deliver roughly a thousandth of Blighty's energy needs. You can see why Shell doesn't view it as a critical part of its future business. ®