This article is more than 1 year old

The GUI that almost conquered the pocket

Farewell then, UIQ

The death of UIQ deserves a footnote for posterity – and a chance to take look back at a decade in which almost everything that everyone predicted for mobile data proved to be wrong. Given the way the market turned out, it didn't stand a chance.

In case you missed the news, the adventure is over. While much of UIQ survived the summer acquisition of Symbian by Nokia, the venture lived on until the start of the month, thanks to joint-owner Motorola. Motorola had 11 UIQ phones (or variants) planned for release next year, and now all have been cancelled in the most recent company reorganisation. It will be cold comfort for Sony Ericsson staff in Warrington (for example) that Motorola's huge Linux effort is also being sidelined, as both are losers in the latest game of musical chairs. With Motorola ending its Symbian investment, most UIQ staff have been given notice.

But why poke this particular corpse while it’s still warm? Indeed, why celebrate an obscure phone UI at all? The number of devotees on the fan boards must be measured in the low hundreds, if not dozens.

Well, it's not because it leaves the world bereft of mobile user interfaces. In the past year, two more rich mobile UIs have appeared on the market with Apple's iPhone and Google's Android. Nor is it because UIQ leaves a technical vacuum - sure, it was good, and is well-liked by Symbian developers. Markedly so, in comparison to Nokia's S60. (As one Nokia marketing staffer admitted recently: "Pretty much the only community around S60 is the community we pay to be there".)

No, UIQ deserves a mention for posterity because for a little while, it brought high-end functionality to a genuinely cheap, easy-to-use mass market device, and it sold by the million. It was a kind of Trojan Horse, and held the a reward for the winner of the smartphone wars. For much of the Noughties, the conventional wisdom maintained that smartphones would dominate computing and electronic commerce.

How wrong we were. Today, the rich mobile device business is dominated by two "appliances": Blackberry and the iPhone. Of the 100 million-odd Symbian phones sold by Nokia so far, these are general purposes devices whose primary purpose is voice. No one disputes their capabilities - Nokia's hardware engineers regularly perform miracles. But today, only a small part of the market chooses smartphones, and a very small number of people use the capabilities of S60 phones in particular. Once you had a P900 and P910, it was harder not to tap into this.

So UIQ's fate mirrors the fate of the general-purpose smartphone. Instead of shipping half a billion, numbers fell way short.

A brief history of UIQ

UIQ had already put years of development and parental turmoil behind it by the time the P900 phone appeared five years ago. Ericsson originally designed the UI in its Ronneby Soft Center lab as a response to the success of the Palm Pilot. Back then, Ericsson boasted 100,000 staff worldwide (it's now around 20,000). It wasn't going to let the success of what in 1996 became the fastest-selling consumer electronics item in the US go without a response. But it needed an OS, and that was some way of being mature enough to use in a phone.

Quartz, now UIQ, took shape in the lab

Symbian acquired the lab from Ericsson in 1999, but for years couldn't decide whether it wanted to keep it or not. A spin out into a joint venture was signed, but not delivered. The first three UIQ phones never made it to market - including Psion's breakthrough Odin communicator, resulting in the engineers producing a slimmer version, and this became the first UIQ phone to make it to market: the Sony Ericsson P800.

Ericsson's unreleased "Pamela" phone: Quartz was subsequently slimmed down

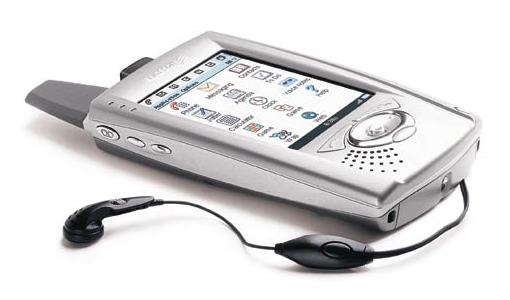

In some ways, the P800 was the iPhone of its day: it raised the bar for what you could put in a handheld device, and it did so by making the competition look Neanderthal. The user experience had its rough edges [2003 Reg review], but most of these were ironed out when the more corporate-looking P900 appeared six months later.

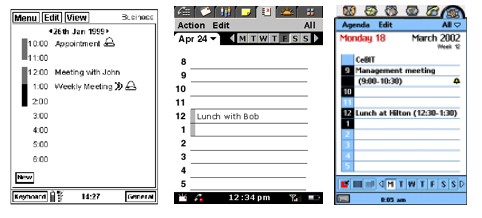

Remember that in 2002, almost all phones and PDAs in use had monochrome displays. High-end Pocket PCs were bulky, and when weighed down with "sleds", required a very strong coat pocket. If you were perverse enough to want to "browse the web", you found yourself staring at a four-line character mode display. How can we forget WAP? Then, along comes a tiny gadget that can render the web in all its all its HTML finery - including certificate management. There was a Palm in there too, although it didn't have the grace or economy of Palm's UI.

The P series was very easy to use one-handed, flexible and reliable. It was a great platform on which Sony Ericsson would build.

The rise of the feature phone

But by 2004 it was clear that the biggest threat to Symbian and would-be Symbians (including Microsoft and Linux) was the competitor the executives had feared all along - dumbphones. The demand for features that justified the complexity and expense of a smartphone simply wasn't there. After one notorious quarter in which market leader Nokia lost six market share points, no manufacturer ever neglected their midrange feature phones again. And the ODMs (original device manufacturers) weren't exactly queuing up to spend money on a smartphone OS.

As Jean-Louis Gassée described it this summer, when Nokia took over Symbian and announced it was giving away the code:

"Handset makers don’t (or didn’t) actually care for software and don’t want to pay anything of significance for it. They (and their masters, the carriers) spend much more money on the nicely printed cardboard box than on the software inside," he wrote.

So smartphone development became a classic chicken-and-egg dilemma. The demand didn't justify the investment. Extra investment didn't stimulate demand.

Smartphones just got dumber

The exception to this stalemate was the shining success of the P-series. But Sony Ericsson was unable to update the phone quickly enough, and it quickly lost its lustre as a technology leader. When Sony Ericsson eventually did give the hardware a long overdue refresh, (with UIQ based on Symbian OS9) it badly hurt the perception of the flagship.