Businesses today function effectively only when the organisation supports effective collaboration between its staff and external parties, wherever they may be situated. Such is the nature of routine operations that they depend on complex interactions between people and their supporting IT systems that spread far beyond the IT firewall and, indeed, the business itself. Clearly this nature of working has profound implications for those charged with securing the operations of the business and the IT systems they use.

It is also undeniable that the pressures inherent in modern business, especially the demand to respond rapidly to quickly fluctuating market conditions and customer expectations along with the need to work closely with third parties, are stressing IT security – this can manifest itself in individuals looking to circumvent security mechanisms just to get the job done. However, this is symptomatic of an increasingly visible factor that is placing further tension on securing systems, which can be summed up as the ‘expectations of people’. It took me many years of interpersonal training to use the noun ‘people’ or ‘customer’ instead of the, perhaps more pejorative ‘user’.

As has already been mentioned in an earlier article in this series, people are far more mobile than ever before and unlike in the distant past, say two or three years ago, now people expect to be able to access all IT services on which they depend from almost any location, be it the home office, hotel bedroom, airport lounge, train bus and coffee shop. With the continued existence of security threats, and indeed the active growth of economic threats, IT increasingly requires to manage all devices utilised by users, especially those who are mobile or who are working from outside of the enterprise firewalls.

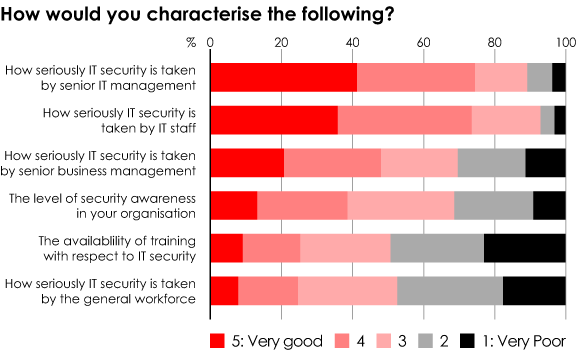

The need to manage the security of devices coupled with the inherent expectation that people have that the device ‘belongs to them’ creates challenges. This becomes very apparent when one looks at some of the results from a Register reader study we conducted last year, outlined in the figure above. Even amongst IT staff, security is by no means taken ‘seriously’ by everyone, and when we look at the general workforce it is evident that both IT security awareness and overall attitudes leave a lot to be desired. Perhaps most worryingly of all it is evident that the availability of IT security related training, usually regarded as the most effective means of raising security, is not readily available in four organisations out of five. If we are expecting the people in our organisations to become their own security administrators, can we honestly say we are giving them the knowledge and tools they need for the job?

The same can be said of how to balance opening the corporate boundary for remote/mobile staff and partners alike, whilst ensuring the security of service provision. Such efforts have seen only limited success, despite the work of more progressive industry consortia such as the Jericho Forum . It is no easy challenge of course – the current thinking is to treat the security of internal systems and networks as if they were connected directly to the Internet, which is good theory particularly given that threats are just as likely to be propagated from infected personal equipment. However, this can be very difficult to carry out in practice.

So just how can the balance between ‘locking down’ and ‘opening up’ be safely achieved? Well the first step is to ensure that the organisation has a policy in place that states, very clearly, that all corporate IT equipment will be managed by the IT department (or whosoever is providing the device management service). It should also explain why and exactly how the management of the devices will be achieved along with stating the responsibilities of the user of the device in the process.

Corporate IT security policy should also scope precisely what, if any, ‘freedom’ the user shall have to personalise a device and how this can be achieved without negatively impacting security. Such policies can work closely with procurement, to ensure maximum flexibility without increasing risk; they can also specify what minimum necessary security requirements and policies are to be imposed on corporate and employee-procured equipment, whether they are connected directly to the LAN or onto the Internet.

For routine security to be effective our research has shown that formally training the users of systems, especially those making use of mobile devices, in how to operate securely is the most effective measure that can be taken. Clearly machines need to be patched in line with the software providers’ directions and all necessary end-point security tools need to be installed and kept up to date. But it is also important that behavioural patterns be taught that reduce the potential for the machines to become compromised or for data to be lost or stolen. ‘Communication’ is the key.

In the longer term it is likely that new solutions, especially in the realm of virtual desktop systems and holding all data centrally or the routine encryption of locally held information will enhance security whilst adding more scope for individuality to be displayed. But until everyone treats security with the respect required there will be a need for ongoing education of every business user of IT systems to raise awareness of security concerns and how easily security can be compromised, either by accident or design.