This article is more than 1 year old

Cyberwarriors on the Eastern Front: In the line of fire packet floods

Former senior Estonian defence official talks cyberwar

Interview Estonian government ministers and officials deep in a crisis meeting about riots on the street in April 2007 were nonplussed when a press officer interrupted them to say that he was unable to post a press release.

The initial reaction was "why are you bothering us with this" Lauri Almann, permanent undersecretary at the Estonian Ministry of Defence at the time told El Reg. "It was only when he said 'No you don't understand, I think we are under cyberattack' that anybody took notice," he explained.

Estonia, a small country of around 1.3 million people bordering Russia and the Baltic Sea, has moved swiftly since independence in 1991 to develop an advanced network infrastructure for the delivery of government and financial services. The country completely skipped the phase of banking involving cheques, for example, so that the vast majority of its citizens use online banking to pay bills and carry out other day-to-day tasks. The disruption when these facilities abruptly ceased to work was therefore all the more severe.

Cyberblitz

Both government and private sector systems in Estonia came under fierce cyber-assault in April 2007. This coincided with street-level riots that accompanied the relocation of World War II (Soviet era) memorials. The riots pitted ethnic Russians in the country against ethnic Estonians and the police.

The denial of service attacks that kicked in around two days after the street protests began left important government, banking and news media websites unavailable. The unavailability of government and news media websites was important because it prevented the government getting information out at a time of crisis. Estonia does not have BBC and CNN bureaus and the culture of using the radio to get news, if all else fails, isn't as ingrained there as it would be in the UK, for example. More Estonians rely on the web for news so the attacks left them deprived of updates.

The first wave of "brute force" packet flooding assaults was followed by more sophisticated attacks, including website defacement, and site takeovers. For example, a fake apology over the relocation of the monuments was posted on the website of one political party.

In total the attacks lasted around three weeks. "It could have been much worse," Almann explained. "We thought they might go on for up to three months. Technically the attacks we faced were nothing special," he added.

In the line of fire

Estonia responded to the cyberattacks, in part, by increasing bandwidth and organising backup hosting for government websites. The process of replicating content in the midst of the ongoing attack was unsurprisingly difficult. "Many countries refused to take our sites because they said that would put them in the line of fire," Almann said.

Speculation since the attacks, a landmark event in computer security, suggest they were fermented in the "Russian blogosphere" and may have involved criminal hackers turned patriots.

Some have suggested that the Russian government may have played a role in encouraging these attacks, a charge dismissed by the Kremlin. Estonian Foreign Minister Urmas Paet, for example, pointed the finger of blame directly at the Kremlin.

A question of attribution

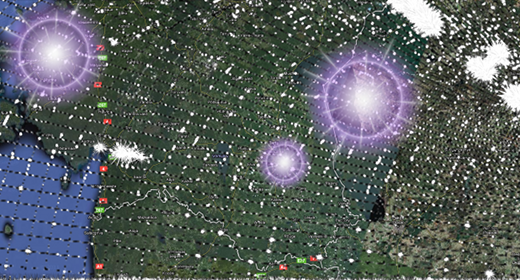

Almann was more circumspect. An estimated one to two million compromised machines in 100 different jurisdictions, including the Vatican, were used in the cyberattacks against Estonia. The use of botnets, which can be rented and paid for anonymously on the digital underground, makes tracing the real source of attacks difficult, maybe impossible.

Instead of relying on purely technical attribution to find a "smoking gun" political and legal attribution also has a role to play.

Almann said that many countries helped Estonia at the time of the attacks with one important exception – Russia. "Russia failed to help put out the attacks. Repeated requests for assistance were denied, sometimes for obscure legal reasons," he told El Reg.

For example, Estonia and Russia have an agreement covering the investigation of cross-border crime which covers the exchange of info as well as the extradition of suspects who might decide to skip over the border to avoid justice. "Treaty requests for information at the time of the cyberattack were repeatedly refused or not acted upon. This refusal to co-operate provides political attribution for the attacks," Almann said.