This article is more than 1 year old

Patrick Byrne: 'See, I told you America's economy was busted'

The battle beyond naked shorts

Overstock.com CEO Patrick Byrne has declared another victory in his six-year fight to expose fundamental flaws in the American financial markets.

With a piece detailing what it calls "America's dodgy financial plumbing", the latest issue of The Economist addresses the very problem Byrne has fought so hard to uncover: naked short selling and other financial trades where the seller fails to actually deliver securities to the buyer. Over the years, Byrne has roundly criticized the financial press for turning a blind eye to the problem, which reached its height amidst the 2008 Wall Street meltdown.

"Remarkably (to me), no matter how much data I had, no matter what insiders and financial experts I could present to explain how this issue was likely world-historic, the US press would not touch the story, no matter how many binders of data were held under their noses," Byrne said over the weekend in an email to friends. "Now, at last, The Economist has picked up the story, and gotten it exactly right."

Byrne tells us he played no direct role in The Economist piece – or a subsequent story along the same lines from The FT. This is hardly the first time the issue has made its way into the mainstream press, but even after the SEC tightened its rules on naked short selling after the crisis that brought down Lehman Brothers and Merrill Lynch in 2008, Bryne felt the media failed to acknowledged the depth of the problem. The Economist's piece is unequivocal.

Patrick Byrne

"The financial crisis of 2007-09 and the 'flash crash' of American stockmarkets in May 2010 revealed numerous faults in the plumbing," the publication says. "Efforts are under way to mend these, but regulators have been slow to attend to some worrying new blockages arising from today’s high-frequency and tightly coupled markets." These blockages include "fails to deliver", where the seller doesn't cough up the security in the allotted time.

The SEC may have cracked down on naked shorting, The Economist explains, but the same basic trick is still widely used in other markets. "Like squeezing a balloon, the problem has simply moved to markets where fails are not penalised."

The problem has become particularly acute with mortgage-backed funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs), investment funds that trade on exchanges much like stocks. Last year, according to The Economist, ETFs covered nine per cent of the trading volume on American equity markets – and almost two-thirds of the value of all fails to deliver.

"These funds have mushroomed of late, spawning all manner of innovations, some of which may be destabilising and worry regulators. Not the least of their concerns is the number of failed trades," The Economist says. "One suspicion is that some brokers may be using naked-shorting of ETFs as a way to get around the restrictions on the practice in plain equities (these don’t yet cover the funds)."

For years, Overstock.com was a fixture on the SEC's Regulation SHO Threshold List, which identifies companies whose stock is involved in an unusually high number of fails to deliver. Byrne believed Overstock was being targeted by traders looking to feed their fortunes by essentially creating "phantom shares" in the company, and this was the start of his very public crusade against naked short selling.

“You can destroy these companies, and when that happens, you don't have to pay the IOUs off."

With a short sale, you borrow shares from someone else and promptly sell them off, anticipating that the price will go down. Then, when the price does drop, you buy the shares back and return them to the original owner. A naked short sale works much the same way – except you don’t really borrow the shares. Three days after the sale, when it’s time to actually deliver shares to the buyer, you fail to do so. Byrne claimed that Overstock was the victim of heavy naked shorting designed to push down the value of the company's stock and ultimately drive it out of business.

"You can destroy these companies, and when that happens, you don't have to pay the IOUs off," he told us in 2007. "It's basically a system for being a serial killer of small companies."

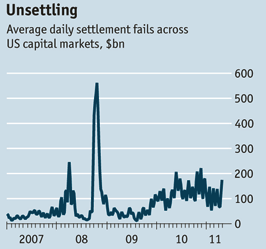

Unsettled trades in US capital markets

(courtesy of The Economist and Basis Point Group)

Many in the press argued that Byrne was merely bitter because his company's stock wasn't performing, and when he stepped up his crusade – most famously with his "Miscreant's Ball" conference call in which he claimed a "Sith Lord" was out to destroy Overstock – he only hurt the cause. At least in the short term. Byrne is the rarest of executives, a CEO unafraid to speak his mind. His methods are eccentric, and most of the press, including The Register, failed to see past those eccentricities.

Byrne claimed there was a conspiracy to discredit him, and at least on some level, he was right, as was demonstrated by the bizarre story of former BusinessWeek reporter Gary Weiss, who commandeered the relevant Wikipedia articles as part of his dogged efforts to discredit Byrne.

When the SEC tightened up its rules on naked short selling in 2008, and Byrne claimed more than a little vindication. But as The Economist points out, the problem is far from solved. And, Byrne says, the American press has never admitted how big the issue is. "At first, I put it down to indolence, conformity, and lack of intellectual horsepower, but gradually came to see it in at least some cases as an extension of regulatory capture," he says.

In his weekend email to friends, he gave a nod to The FT as well as The Economist, but his distaste for the American financial press endures. "Apparatchiks," he said. ®