This article is more than 1 year old

The life and times of Steven Paul Jobs, Part One

From grade-school hellion to iMac redemption

From babysitter to billionaire

Nineteen ninety-four began as a lost year for Steve Jobs – though not for two-year-old Reed Paul Jobs nor, presumably, for Laurene Powell Jobs, Steve's wife of three years. According to numerous sources, Jobs spent a lot of time at home during that period – especially during the beginning of the year.

In February, however, he received good news. After Disney halted the Toy Story project in its tracks, Pixar's creative genius John Lasseter and his staff had taken Katzenberg's criticism to heart, and had rewritten the script. When they took it back to Disney, Katzenberg green-lighted it. Pixar was back in the movie-making business.

At first, Jobs was less than excited about the project, and tried to peddle Pixar to a few potential buyers, including Microsoft.

The turnaround of Jobs' opinion of Pixar came when he attended a lavish Disney event in New York's Central Park in January of 1995 to showcase clips from two of that year's blockbuster animations: Pocahontas, scheduled for summer, and Toy Story, scheduled for the lucrative Thanksgiving time slot.

The three men who made Steve Jobs a billionaire: Buzz Lightyear, Toy Story writer/director John Lasseter, and Woody

Ralph Guggenheim, Toy Story's coproducer, told Alan Deutschman that "Steve went bonkers" at the attention that the Pixar film received at the event, which was attended not only by Disney's top execs, including CEO Michael Eisner, but also New York mayor and celeb Rudi Guliani, plus assorted other VIPs.

"This was the moment when Steve realized the Disney deal would materialize into something much bigger than he had ever imagined," Guggenheim recalled, "and that Pixar was the way out of his morass with NeXT."

After that event, Jobs became more involved with the day-to-day workings of Pixar. In February, he hired away EFI's CFO Lawrence Levy to take the same position at Pixar, with the goal of taking the company public – and, audaciously, to schedule the IPO for immediately after the Thanksgiving debut of Toy Story.

If the movie were to be a success, the buzz surrounding it would fluff the IPO. If it flopped, so would the IPO.

Toy Story debuted on November 22; the IPO was held on November 29. Toy Story was the number one movie in the US on its opening weekend, and went on to be number one for its first three weekends, then number one again during the Christmas/New Years holiday break.

Pixar's first feature was the number one grossing film of 1995, and went on to eventually gross exactly $361,958,736 worldwide, according to Box Office Mojo.

And the IPO? Shares of Pixar – a company that had lost money each year beginning in 1992 – had been pegged to be offered at $12 to $14 in a preparatory SEC filing, but opened at $22 during the first day of trading on the NASDAQ exchange. Shares rose as high as $49.50 during that day before settling back to $39.

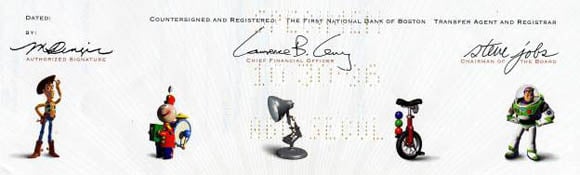

Specimen Pixar IPO certificate with Steve Jobs' signature (source: Scripophily.com)

Jobs held 80.2 per cent of Pixar's shares. The IPO made him a very wealthy man. As David Price put it in The Pixar Touch, "Following the IPO, his shares of Pixar were valued at more than $1.1 billion – and the rounding error on that figure was almost as much as the entire value of his Apple holdings when he left Apple a decade earlier."