This article is more than 1 year old

Critical Windows zero-day bug exploited by Duqu

Trojan used booby-trapped Word file to spread

The Duqu malware used to steal sensitive data from manufacturers of industrial systems exploits at least one previously unknown vulnerability in the kernel of Microsoft Windows, Hungarian researchers said.

The zero-day vulnerability was triggered by a booby-trapped Word document that was recently discovered by researchers from the Laboratory of Cryptography and System Security, or CrySyS. The security consultancy provided bare-bones facts on its homepage, and researchers from Symantec elaborated on them here. The Word document was phrased in a way to “definitively target the intended receiving organization,” Symantec researchers said.

Duqu generated intrigue almost immediately after its discovery was announced two weeks ago because, according to CrySyS and Symantec, its source code was directly derived from the Stuxnet worm used to sabotage Iran's nuclear program. Tuesday's update begins to answer some of the key gaps contained in the initial reports, including how the malware infected computer networks, whom it targeted, and exactly what it was programmed to do.

It also provides new details that reinforce claims that it's a highly sophisticated piece of malware that was designed for a very specific purpose.

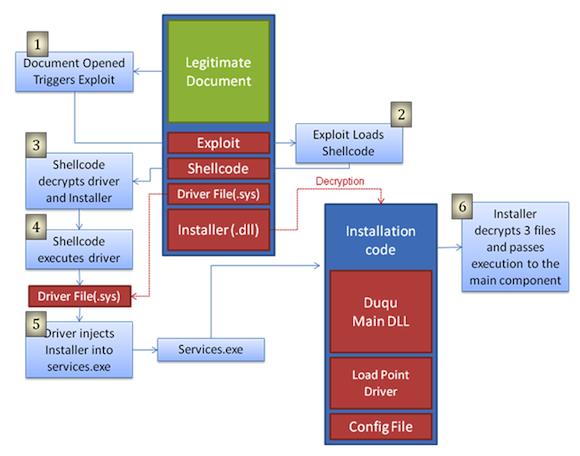

According to Symantec, the Duqu installer file is a Microsoft Word document that exploits a previously unknown kernel vulnerability that allows code execution. Opening the file installs the Duqu remote access trojan that conducts surveillance on the infected networks.

This graphic published by Symantec shows how the Word document exploited Windows systems

Microsoft researchers are working with partners to protect Windows users against the attack, including through the release of a security update, the company said in a statement. There are currently no workarounds users can follow to insulate themselves against the threat, other than to follow standard safe practices, such as not opening suspicious files attached to emails.

Interestingly, the code contained in the Word document ensured that Duqu would be installed during a single eight-day window in August, most likely in a bid to conceal the attack or to minimize the damage it might cause. As previously reported, the main binaries of the trojan were configured to run for 36 days and then automatically remove it from the infected system.

In at least one organization that was infected, evidence suggests Duqu was able to spread across networks through SMB connections used to share files from machine to machine. Even when some of the newly infected computers had no access to the internet, the malware on them was still able to communicate with attacker-controlled servers by using file-sharing code to route the connection through an infected computer that did have internet access.

“This allowed the attackers to access Duqu infections in secure zones with the help of computers outside the secure zone being used as proxies,” Symantec researchers wrote.

The researchers also said Duqu appears to have infected six organizations in eight countries, including France, Netherlands, Switzerland, Ukraine, India, Iran, Sudan, and Vietnam. It's possible the number may be smaller. Some of the organizations were traceable only to the ISP they used, so some of the six organizations counted in fact may not be separate.

Symantec researchers also discovered a second command and control server that some versions of Duqu used to communicate with their operators. It was located in Belgium and used the IP address 77.241.93.160. Previously, Duqu was known to use only a control server located in India. Both servers have been taken offline.

While CrySyS and Symantec researchers both say Duqu contains technical signatures proving it was designed by the same developers who spawned Stuxnet, investigators from Dell SecureWorks disagree. All of the perceived similarities are contained only in the component used to inject code into the Windows kernel, they said in a report published last week. The actual payloads, they concluded, are “significantly different and unrelated.”

Their ultimate conclusion: “The facts observed through software analysis are inconclusive at publication time in terms of proving a direct relationship between Duqu and Stuxnet at any other level.”

Symantec has revised one key detail since publishing its findings last week. Previously, it said Duqu infected organizations involved in the manufacture of industrial control systems, such as those used in gasoline refineries, nuclear power plants, and other industrial facilities. In an update, the researchers said that term, and the previous use of the term SCADA (short for supervisory control and data acquisition) wasn't technically accurate. The firm now says Duqu targeted “industrial industry manufacturers.”

Researchers continue to search for files that might have been used to install Duqu on infected machines, so it's possible the attackers may have exploited other zero-day vulnerabilities. Stuxnet targeted at least four zero day bugs. ®