This article is more than 1 year old

The Google Review, explained...

Immense wealth awaits. Email Ian Hargreaves with bank details, statute book

Now we know why what was widely called the "Google Review" into intellectual property came to the conclusions it did. And we have it from the horse's mouth: not Google, but Professor Ian Hargreaves and his team at the IPO, who "guided" him.

If you recall, a year ago the Prime Minister David Cameron revealed that the Google founders that they could never have founded Google in the UK, because of its copyright law. Even Google could never substantiate the quote, or provide a citation. Rather than getting a public inquiry, and shaming, of a foreign corporation for misleading our PM so badly – Google got the government to explore how the law could be altered... to benefit companies like Google.

So the review began with a mistake, and its guiding philosophical idea was a naive, simplified, and fantastical version of the world. This set the tone for what followed.

Hargreaves came across as wry and likeable, as he always does, but his words revealed the bien pensant view of the internet, its potential, and its commercial challenges.

Ian Hargreaves

"Politicians are afraid to address [copyright] because of fear of damaging the entirely legitimate and desirable wishes of musicians and other creators to have a fair level of protection, so they can make a return on their own work. I do disagree how this machinery has spread, and become an undesirable regulatory restraint on the internet [our emphasis] and the internet's effects on the economy.

He continued:

"That is a very, very big risk for an advanced knowledge economy like the UK to run. In my view we can't afford to run it. It's urgent; the government has to take the action I have recommended it take".

The sky was falling, he'd felt a piece of it land on his head. And he hammered home this urgency in his conclusion, in case you missed it:

"The digital revolution is not one-third complete, based on the penetration of the internet around the world. If we don't 'Get with the Pace', we will pay a significant economic price."

There are several flaws to this approach.

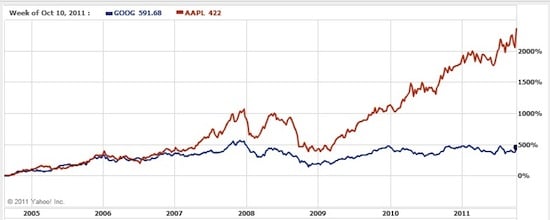

The graph below illustrates the recent commercial fortunes of two technology companies. One of these has negotiated with incumbents and innovated to establish platforms that create new markets. It didn't lobby for the rules to be changed. It worked with what rules there were. It created an explosion of economic value.

Fortune favours the brave: not the lobbyists

The other company, by contrast, lobbies intensively for the rules to change (one of the recipients of its cash shared the stage with Hargreaves), so its costs can be lowered. It's why we were here. The first is Apple, and the second is Google.

Now, what this shows that there is more than one approach to dealing with incumbents and the legal and regulatory status quo. The empirical data here clearly tells us that platform creation within the rules is not only possible, but actually far more lucrative than the slightly sleazy backroom business of lobbying for the rules to be changed. It also demolishes the "pace" argument – which is an appeal to the Precautionary Principle: that if we don't do something drastic very soon, we'll face a far greater cost. (See Iraq, WMDs). By creating markets for digital content, Apple ran counter to the perceived wisdom of internet gurus that people would never pay for it. Newspapers have followed suit with paywalls, with some success. Apple killed Free.

Hargreaves' view of internet growth is based on one particular view of the world – and it happens to be one one that isn't very good at producing growth. Hargreaves is evidently a decent and intelligent man, he is just basing his judgments on a view of the world that is Utopian, and feels very dated. This leads to the other problem, which is that his argument is based on exceptionalism, and makes demands of groups that it shouldn't.

Viewed sociologically, the argument is that one group needs to become weaker, just so another can prosper. History shows that time and again, technological innovation allows many parties to prosper – no technology content market has yet done otherwise, or removed rights. If I was an internet guru, I would call this the Orlowski Principle, and Tweet it like mad. But it's actually the way good policy is conducted since the Enlightenment.

Yet for some reason, Google prefers to seek to change the rules rather than create new markets. Your speculation on why they adopt this approach might be is as good as mine.

This Google isn't working

Google isn't very good at consumer products, as the late Steve Jobs told Larry Page, but it should be able to do large scale platforms. Maybe it isn't very good at doing the negotiations – with finance and creative industries – needed to push this through. Maybe all of its best ideas are invisible. Maybe it doesn't do ideas. Maybe it's innately fearful and conservative – as large record companies were for years, clinging to the CD, and failing to create digital markets or physical replacements.

Google is still a one-club golfer, and that club, its advertising brokerage, doesn't really begin to unlock the potential value – as Apple's content store has shown. Whatever the reason(s) may be, academics such as Hargreaves seem not to have really taken these developments on board: they appear only too keen to endorse Google's view as the one true way of achieving growth.

For Hargreaves, the internet creates such a unique, singular moment of historical anxiety, we can suspend traditional ideas of fairness. It shouldn't make us deaf, though.