This article is more than 1 year old

Cisco boasts of 10,000th server customer

$1.1bn in iron a year, and snowballing

The jury is still out as to whether Cisco Systems' foray into servers hasn't done more harm than good to its overall business, but one thing seems certain: the business is growing. Cisco's iron is competing and the Unified Computing System blade and rack servers cannot be called a failure.

Earlier this month, Cisco added its 10,000th server customer and the company, which has been under intense pressure in its core router and switch business in the past two years, wanted to brag a bit about how this business is growing – and about who is buying its server iron.

Cisco launched itself into the server racket with its initial UCS B Series blade servers in March 2009, which shipped in August of that year, and added its C Series rack servers in June. The machines feature converged 10 Gigabit Ethernet networking, which both links servers to each other and to external storage; an integrated UCS Manager system management tool that can hook into hypervisors; and Cisco's virtualized I/O in the UCS systems to manage the whole shebang. (Cisco will support just about any hypervisor but has partnered heavily with VMware for its ESXi hypervisor and distributed virtual switch. Cisco has also OEMed BMC's BladeLogic system and application management software as an option for the UCS iron to do some of the functions that UCS Manager cannot.)

Three years ago, server and storage networking was converging and server-makers Hewlett-Packard, IBM, Dell, Oracle, and Fujitsu were all selling their own or acquired or rebranded data center switches – and clearly looking for a convergence marketing pitch to get a bigger slice of the IT pie. Cisco's entry into the server racket was not just predictable, but inevitable and unavoidable. And more than anything else, Cisco, with its fat cash pile and credibility in the data center, shook up the server business and accelerated the networking plans of the tier one server makers. Cisco's entry into servers has been good for the industry even if it is arguable from a financial standpoint whether the business is profitable – and whether Cisco's jumping into servers didn't hurt its core networking revenues as former partners became competitors. Cisco obviously came to the conclusion that such a pivot was unavoidable, and with typical Cisco flair went at it.

As El Reg previously reported, in the most recent quarter for which data is available (Q3 2011), Gartner reckons Cisco sold 39,800 blade and rack servers and nearly tripled its revenues to $268.3m. Todd Brannon, marketing manager for unified computing at Cisco – and the former market development manager for Dell's Data Center Solutions (DCS) bespoke server business for hyperscale data center customers – tells El Reg that as Cisco ended 2011, the UCS server business was generating product orders at an annualized run rate of $1.1bn.

Cisco has not talked about aggregate revenues and shipments for UCS since its launch, and deferred to box counters at IDC to get "official" numbers. (Cisco doesn't report server shipments and sales in its financials, so it can't divulge them to press or analysts selectively.) IDC had not returned our call for comment at press time.

What is obvious is that Cisco's server business is growing very fast (as is Chinese PC-maker and now server-maker Lenovo) and is taking market share away from the incumbents in doing so. In the third quarter, Gartner said that server revenues were up 5.2 per cent to $12.97bn and shipments rose by 7.2 per cent to 2.37 million units. Cisco is growing fast, but has still not broken into the top five. The question is whether Cisco is in the position that Sun Microsystems was in when it entered the x86 server racket with affordable and respectable Opteron-based machines back in 2004. Sun's x86 server business grew very fast, and then flattened out at the same time that its UltraSparc server business tanked.

Brannon cites IDC data he had on hand for the blade market, where Cisco is getting most of its UCS revenues. In the third quarter, Cisco had a 12.1 per cent share of the worldwide $2bn blade server market, which was a factor of 10 revenue growth compared to figures from IDC for the third quarter of 2009.

HP still had a commanding 48.9 per cent slice of the blade pie in Q3 2011, but lost 1.4 points of share over the two years. IBM had 18.9 per cent revenue share in blades in the third quarter, a drop of 10.2 points of share. Other vendors in the blade racket wiggled up and down a little, but there are two things to note. First, Dell's revenue share in blade servers is about the same at 8.1 per cent, and second, Cisco's growth almost precisely matches the decline in IBM's sales.

In the US market where Cisco is doing best in servers, the company has 19.4 per cent revenue share, just two-tenths of a point ahead of Big Blue and a considerably larger slice than Dell's 7.4 per cent share. HP had a 50.5 per cent slice of the blade server sales pie in Q3 2011 in the States, and gained 2.7 points of share.

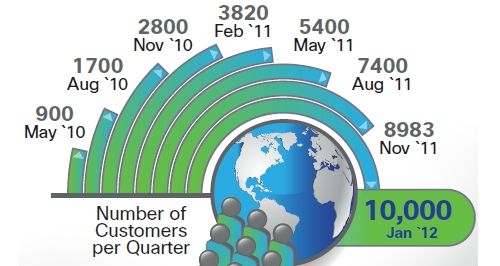

What Cisco has talked about – in addition to an occasional reference to the annualized UCS run rate since it got into the server biz – is the number of unique customers who have bought UCS iron. Here's how the base has grown over time:

Cisco's UCS customer count over time

Cool customers

If you plot those numbers on a chart, you'll see that the customer count accelerated as Cisco came out of 2010 and up through early 2011, with the company averaging about 325 new customers per month during this time. Cisco added customers at a fast rate in the spring and summer of last year, and the rate tapered off a bit in the fall. The company is now facing the limits of large numbers in its comparison, but there's another thing to consider: Cisco has very deep relationships with most of the top companies in the world with the largest data centers. The total addressable market for UCS iron is very large, even if Cisco never sells a single server to a small or medium business and does not put a dent in the general purpose server businesses of HP, Dell, IBM, and Fujitsu.

"The rapid adoption that we are seeing is a direct result of how unified computing changes the economics of the data center," Brannon tells El Reg, saying that customers are seeing as much as a 40 per cent savings in their server, storage, networking, and administration costs compared to unconverged stacks. "Customers are not interested in science experiments. They are telling their friends and neighbors, and this is snowballing."

Who are these customers? Brannon says that they reflect the makeup of the global economy at large, with a slight "pear shape" toward the United States. As you might expect, service providers are a big part of the initial UCS customer base, since they are keen on building clouds and lowering operating costs. The Cisco installed base, says Brannon, tends to be slightly more virtualized than the server market at large and tends to be skewed towards partner VMware, which rules virtualization in private data centers these days. That said, Cisco has plenty of customers deploying applications on bare metal, which UCS Manager can handle as well.

Cisco also tends to get business for greenfield installations of new applications, such as private clouds. And once customers install a bunch, they come back for more. About a third of those 10,000 customers have come back again to buy more servers, says Brannon, and in those cases, the average number of times they come back is 3.4 times.

Sometimes, you need a bigger boat

The other thing that is happening, of course, is that Cisco is now seeing more uptake of its C Series rack servers now that customers have put the B Series blades through the paces. The mix is starting to shift to a more balanced sales rate for blades and racks at Cisco, although Brannon was not at liberty to be precise with numbers. "Sometimes, it is like the movie Jaws: You are going to need a bigger boat. Sometimes you need a rack server," says Brannon, because of the memory, peripheral, and I/O expansion that a particular workload demands.

But, according to Brannon, the one thing that Cisco doesn't think its customers need is a really big boat. IBM, Oracle, Fujitsu, and NEC have eight-socket servers using Intel's Xeon 7500 and E7 processors, but Cisco and Dell do not. Brannon says that the price/performance sweet spot for the workloads that Cisco is targeting – enterprises wanting virtualized or bare-metal server instances to run database, infrastructure and applications on Windows or Linux and service providers building clouds – is two-socket and four-socket Xeon machines.

Cisco has no plans to launch Opteron-based machines (or at least any that Brannon can talk about publicly) and similarly has no plans to build ARM-based servers, although Brannon did concede that Cisco's server product team "is evaluating everything" to build out its server business. The company is not going to chase the super-low-cost, hyperscale server nodes embodied in HP's experimental "Redstone" ARM servers, which are based on a modified quad-core Cortex-A9 chip, called the EnergyCores, made by Calxeda.

"Customers are not coming here and saying that they need more compute per square inch," says Brannon. "They have management and complexity problems, particularly around physical and virtual I/O."

The one thing that Brannon will admit that Cisco is working on for this year is to expand the management domain size of the UCS Manager. This control freak at the heart of the UCS system can scale up to 20 chassis and a total of 180 server nodes in a single management domain. Some cloud providers and private enterprises want to add more servers without adding management domains. This is true for every cloudy management tool provider, by the way. ®