This article is more than 1 year old

WTF is... 802.11ac?

Next-gen Wi-Fi beamforms in

Wireless networks are never fast enough, but for the moment at least they are generally quicker at shifting packets of data than the broadband connections they're typically linked to.

That's changing. Broadband speeds are rising, especially those fed through fibre-optic lines. Fortunately, Wi-Fi is keeping up. A number of chip and networking kit makers used the recent Consumer Electronics Show (CES) to tout their support for IEEE 802.11ac, a new wireless standard.

The technology uses the 5GHz band already utilised by the old 802.11a - big with corporates, but never a favourite of consumers - and the more recent 802.11n.

The 'n' standard can use 5GHz for speedier operation. The 5GHz band not only runs at a higher frequency than the more commonly used 2.4GHz section of the spectrum - also able to be utilised by 802.11n and its predecessors - but is also far less crowded, not only free from many a neighbour's wireless network but also from noise generated by microwave ovens and other electrical appliances.

Unfortunately, 802.11n is something of a mongrel, an attempt not only to up Wi-Fi's throughput but also to combine all the earlier 802.11 versions. Alas it doesn't mandate including them all, and numerous low-cost 802.11n chips operate only in the 2.4GHz band.

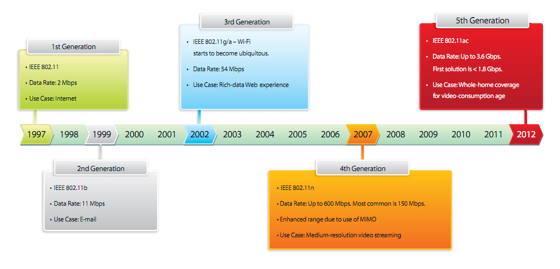

Source: Broadcom

Worse, they deliver a throughput barely quicker than the old 802.11g's 54Mbps. One of 802.11n's innovations was the ability to hook up more than two antennae, one for transmission and one for reception, a technique called 'MIMO' - Multiple Input, Multiple Output. But too many cheap 'n' adaptors stick to that '1x1' aerial configuration. That delivers peak throughput of just 72Mbps. Want more speed? Go to 2x2 and get 150Mb/s, or 3x3 and reach 300Mbps. Recent, 4x4 adaptors will take you to 480Mbps.

802.11ac supports even more antennae, up to eight of them, and it allows devices to negotiate dedicated links through specific groups of aerials to manage multi-client networks more efficiently.

One device may also be set to transmit to multiple others, but not receive. That's handy for beaming one HD video stream from a source to multiple screens throughout the home, say.

The standard has other tricks up its sleeve to boost throughput. It widens the 5GHz band's sub-channels from 802.11n's 40MHz to 80MHz and 160MHz, reducing the data-slowing impact of interference from other networks on other channels.

QAM, QAM, thank you, ma'am

Like 802.11n, 802.11ac uses quadrature amplitude modulation (QAM) to encode binary data into the radio signal. The 'n' standard maps bits onto 64 'constellation points' - effectively wave phase values that are used to represent sequences of bits. The more points you use, the more possible phase values can be selected and so the more groups of bits can be generated at the receiver. 802.11ac uses 256 constellation points.

The upshot: faster data transmission, at a cost of a reduced resilience to noise. That can be countered with better error checking, but that reduces the overall data transmission rate.

Range is a problem in the 5GHz band too. The faster frequency means a lower wavelength than 2.4GHz communications, and that has an impact on the distance over which the signal attenuates. However, 802.11ac mandates 'beamforming' techniques to map the wireless environment it's operating in and so steer clear of inefficient signal paths.

Put all these together and you're looking at raw data speeds of up to 3.47Gbps of one, eight-antenna access point and one, four-antenna client. More realistic scenarios with fewer antennae in the access point and in multiple clients call for speeds of between 433Mbps and 1.73Gbps.

Buffalo's WZR-1750H 802.11ac router

As yet, the IEEE has not formally approved 802.11ac, but the wireless industry, having been caught out before by the often overlong IEEE ratification process, are gearing up to provide 'draft' 802.11ac spec support, betting that the final standard will not changed much - at least nothing that can't be sorted with a firmware fix - and that interoperability testing will ensure firms' own take on the draft will align with others'.

Chip maker Broadcom is leading the way, outing four 802.11ac chipsets at CES, but its rivals are working on the technology too. Broadcom marketing them as '5G Wi-Fi'. Router makers Buffalo, D-Link and TrendNet had 802.11ac compatible kit on show.

Savvy Wi-Fi users have already hopped into the 5GHz band with 802.11n, and they're likely to grab 802.11ac kit when it becomes available later this year for even faster data throughput. UK-based market watcher IMS Research reckons these folk will buy more than 3m 802.11ac devices this year.

Initially, they'll be routers and add-on adaptors for existing 802.11n machines. Laptops and tablets with 802.11ac on board will follow in due course. But it's though that smartphones will stick with 802.11n for the time being. "We believe it might be 2014 before we see the first 802.11ac-enabled smartphone," says IMS' Filomena Berardi. ®