This article is more than 1 year old

Boffins dig up prehistoric popcorn in Peru

Bit soggy now: Man wolfed down treat 6,700 years ago

Mankind was scoffing prehistoric popcorn 1,000 years earlier than previously thought, reckons a top archaeologist.

Before anyone along the arid north coast of Peru bothered crafting ceramic art or making cooking pots, let alone building cinemas and other attractions in which the crunchy snack is often wolfed down by modern Man, hungry folks were roasting corn for fun.

This is according to a new paper in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences* co-authored by Dolores Piperno, curator of New World archaeology at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and emeritus staff scientist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute.

Some of the oldest known corncobs, husks, stalks and male flowers, dating from 6,700 to 3,000 years ago, were unearthed at Paredones and Huaca Prieta, two mound sites on Peru's coast.

The boffins, led by Tom Dillehay from Vanderbilt University and Duccio Bonavia from Peru’s Academia Nacional de la Historia, say the small fossils of corn — the earliest ever discovered in South America — prove that ancient man devoured corn in several ways, including popcorn and flour corn. However, the foodstuff was not an important part of their diet, which is the scientific way of saying it was a treat.

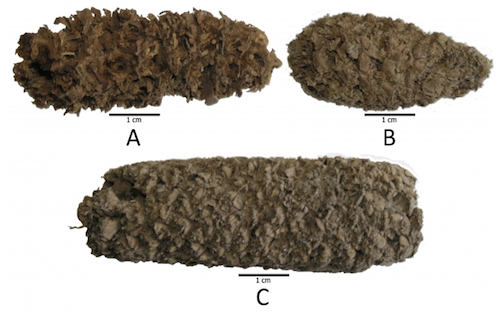

6,500-year-old cobs - tasty: A is Proto-Confite Morocho; B is Confite Chavinense maize; C is Proto-Alazan maize.

"Corn was first domesticated in Mexico nearly 9,000 years ago from a wild grass called teosinte," said Piperno.

"Our results show that only a few thousand years later corn arrived in South America where its evolution into different varieties that are now common in the Andean region began. This evidence further indicates that in many areas corn arrived before pots did and that early experimentation with corn as a food was not dependent on the presence of pottery."

"These new and unique races of corn may have developed quickly in South America, where there was no chance that they would continue to be pollinated by wild teosinte. Because there is so little data available from other places for this time period, the wealth of morphological information about the cobs and other corn remains at this early date is very important for understanding how corn became the crop we know today."

There was no word on whether or not the ancient civilisation preferred salted or sweet popcorn. ®

* Preceramic corn from Pardones and Huaca Prieta, Peru by A Grobman, D Bonavia, TD Dillehay, DR Piperno, J Iriarte, I Holst, 2012, can be found in PNAS.