This article is more than 1 year old

Bletchley Park gets personal with new Alan Turing exhibition

Steampunk speech-scrambler, a note to mum and more

Letters, academic work and personal belongings of wartime codebreaker and computer pioneer Alan Turing, including a letter to his mother explaining his role in the outcome of World War II, went on display at Bletchley Park on Monday.

James May cuts the ribbon on the new Alan Turing exhibition. Photos by Brid-Aine Parnell

The new display, which will eventually also include a rebuild of Turing's speech-scrambling machine, codenamed Delilah, was officially opened by Top Gear presenter James May.

The exhibition came about following a high-profile public campaign last year to save a bunch of Turing's papers collected by his friend Professor Max Newman, which had been put up for auction at Christie's.

Sir John Scarlett, chairman of the Bletchley Park Trust, said at the event today that the fight to save the collection was kicked off when director of museum operations Kelsey Griffin spotted the auction and tweeted for help.

That bagged the campaign some help from Google and private donations, but not quite enough to meet the collection's reserve price at auction. Bletchley then went to the National Heritage Memorial Fund, which provided the shortfall to buy the collection.

After the papers were saved, members of Turing's family came forward with some of his personal belongings from school and university days to add to the exhibition.

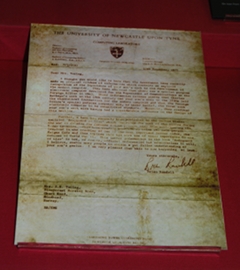

Letter to Alan Turing's mother

The letter to Turing's mother was written by Brian Randell, professor of computing science at the University of Newcastle upon Tyne, 20 years after his death and tells her for the first time the value of his contribution to the war effort and to computing as we know it.

"[The Government's] information release states that Charles Babbage's work in the 19th century and your son's work in the 1930s laid the theoretical foundations for the modern computer," the letter read, adding that a book published in the US credited Turing with breaking the German's Enigma Code, thereby having "vital importance" in the war.

The work done at Bletchley during the war remained a secret until the 1970s, despite the fact that thousands of people had worked there by the end of the war.

Lord Asa Briggs, a Bletchley Park codebreaker, told The Register that he had married his wife in 1955, but she didn't find out about his time at Bletchley until 20 years later.

"We didn't keep those secrets because we'd signed the Official Secrets Act, we kept them because we knew they were essential to winning the war," he said.

Lord Briggs said Turing was a genius, a sentiment echoed by another wartime codebreaker, Captain Jerry Roberts.

Stephen Kettle's statue of Alan Turing at work

"In the spring of 1941, Britain was losing the war," Captain Roberts said. "The German wolf packs (u-boats) were sinking the ships bringing in food and raw materials to Britain left, right and centre... and of course we didn't know where they were out there, waiting, lurking.

"At that juncture, Turing made his fantastic achievement of breaking naval Enigma ... At that juncture, there was no other salvation for Britain, there was nothing else that could have saved Britain, and of course Europe at the same time.

"Once naval Enigma was broken, the sinkings dropped by 75 per cent."

Roberts said Turing also made a vital contribution to breaking Tunny, the code for high level communications including messages sent by Hitler, and briefed Tommy Flowers, the engineer who designed the world's first programmable computer, Colossus.

Sir John Dermot Turing, Alan Turing's nephew, said that the family hoped that the personal belongings in the new exhibition would show Turing as a man, as well as one of the founding fathers of computing.

"You hear about his eccentricities, you hear about chaining mugs to the radiators and cycling around the locality with his gas mask on to ward off hay fever. It can paint a picture of somebody who is mathematically remote and is perhaps too weird to want to get to know," he said.

"What this new exhibition is trying to do is to share some of the more human side of Alan Turing's nature, perhaps to balance out the other picture."

Alan Turing's belongings from school and university days

Among his personal effects are a teddy bear named Porgy, who was the "first audience" for his lectures, English literature books given to him as prizes at school – which Turing joked still looked untouched after 80 years – and sporting trophies from when he used to row for King's College Cambridge.

These are displayed along with some of his academic papers; the already rebuilt Bombe machine, which was instrumental in breaking the Enigma code; and a sculpture of Turing at work by Stephen Kettle. Later this year, the exhibition will also house Turing's Delilah machine.

The speech-scrambling machine, codenamed Delilah

Delilah was a portable speech-scrambler. Turing started working on it in 1943 and demonstrated its mechanisms by encrypting and then decrypting one of Churchill's speeches, but the machine was never commissioned for use in the war effort.

The Bletchley Park Trust Bombe Rebuild Team, led by John Harper, is currently rebuilding the machine for display to the public later this year.

Fundraising for the restoration of the rest of the park, including the huts where Enigma was cracked, is ongoing. Phase one of the work is expected to start this year and be completed by 2014.

Bletchley Park Trust has successfully secured a Heritage Lottery Fund grant of £5m and has raised £1.3m. Phase one of the project will cost £7.4m and total costs are expected to exceed £10m. ®