This article is more than 1 year old

Space probe in orbit above Mercury sees signs of polar ice

First rock from the Sun yields secrets at last

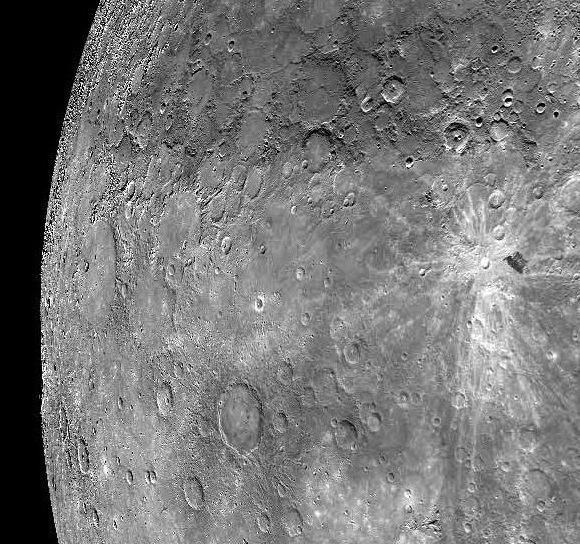

Space boffins reviewing data from a probe craft orbiting Mercury, innermost planet of the solar system, say they have seen signs of glaciers lurking within shadowed craters at the poles.

Gad, it's a barren, heavily cratered desert out there. Except for the icebergs.

The revelations come from NASA's MErcury Surface, Space Environment, GEochemistry, and Ranging (MESSENGER) spacecraft, which is only the second machine of humanity to visit the mysterious world (the first was Mariner 10 back in the '70s). MESSENGER has now been circling Mercury for a year, and has upset many applecarts in the world of planetology.

"The first year of MESSENGER orbital observations has revealed many surprises," says chief probecraft boffin Sean C Solomon, of the Carnegie Institution. "From Mercury's extraordinarily dynamic magnetosphere and exosphere to the unexpectedly volatile-rich composition of its surface and interior, our inner planetary neighbor is now seen to be very different from what we imagined just a few years ago. The number and diversity of new findings being presented this week to the scientific community in papers and presentations provide a striking measure of how much we have learned."

The headliner among the new knowledge is that previously-spotted bright radar reflections near the Mercurian poles have been found to map onto areas inside impact craters which are permanently in shadow. Despite Mercury being so much closer to the Sun than Earth, and thus hotter, the eternal darkness of the crater deeps is thought to make them cold enough that icebergs might lurk there.

"We've never had the imagery available before to see the surface where these radar-bright features are located," says Nancy L Chabot of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab (APL), who is in charge of scrying efforts using MESSENGER's Mercury Dual Imaging System (MDIS). "MDIS images show that all the radar-bright features near Mercury's south pole are located in areas of permanent shadow, and near Mercury's north pole such deposits are also seen only in shadowed regions, results consistent with the water-ice hypothesis."

Us humans always like to find water elsewhere in the universe, as it would make the sustainment of manned bases much easier (furnishing not only drinking liquid but also breathing oxygen and rocket fuel). Nobody's particularly suggesting the colonisation of Mercury, but it's nice to see water there anyway.

If people did go to live on Mercury, it seems they'd also never be short of sulphur: there's tons of the stuff about there, far more than there should be under some previous theories of planetary formation - hence the MESSENGER readings have led to many an arm-waving argument in front of blackboards.

"We didn't expect so much sulfur," admits senior boffin Stanton Peale of California uni in Santa Barbara. Peale says that the sulphurous abundance, coupled with a near-total absence of iron, indicates that the planet's formation was much more disorderly than the boffinry community had believed before MESSENGER arrived.

"Mercury is composed of material that had condensed over a wide range from the Sun," he contends, pugnaciously.

Other revelations include the fact that Mercury's core is huge as these things go, making up fully 85 per cent of the planet, and that its surface is comparatively flat and featureless compared to the mountainous terrain of Earth or Mars.

The new Mercurian boffinry is being presented to an astonished Earth in a flurry of papers and various presentations at the 43rd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (LPSC) in Texas this week, much of which is being streamed live on the internet. ®