This article is more than 1 year old

Space-cadet Schwartz blows chunks out of Oracle's Java suit

Thanks Jonathan. Come back any time

Analysis Google unveiled its secret weapon against Oracle this week: Jonathan Schwartz.

The first third of the IP trial, which is expected to last eight weeks, deals with copyright. Patents and trademark claims come next. This week it was Google's turn to defend itself against Oracle's copyright infringement claims, and Schwartz was the star turn. Schwartz joined Sun in 1996 and 10 years later succeeded Scott McNealy as Sun CEO. It was Schwartz who delivered the company to Oracle in 2009. All of which means he was in charge of the IP that's the subject of this case for much of the time Android was being developed, and when it was launched in late 2007.

Schwartz was on the stand for less than an hour – but managed to trample Gruffalo-sized footprints in Oracle's case.

"We didn't think they [Google] were doing anything wrong," Schwartz affirmed. He also attested that at no time during his tenure did Sun "consider APIs proprietary or protected". An Oracle attorney asked Schwartz if he had been fired by Oracle when the deal was completed in 2010. Ever quick on his feet, Schwartz replied that "They already had a CEO".

Schwartz really couldn't say anything else. One of Google's strongest arguments is that for 18 months after Google unveiled Android, Sun twiddled its thumbs and did nothing. In fact it cooed quite a lot about a "Participation Economy". Only after Ellison's Oracle acquired Sun's IP did the war drums begin.

Which doesn't mean Sun doesn't have a strong claim on its IP case. Copyright claims do not have to be asserted continuously, as trademarks do. But if the jury concludes that Sun was relaxed about how its IP was used, it may limit the damages to a figure far lower than what Oracle wants. (That figure has already been halved).

When Android was launched, Schwartz wished them well in a blog post title beginning "Congratulations Google", calling it "an incredible day".

He continued: "Needless to say, Google and the Open Handset Alliance just strapped another set of rockets to the community's momentum – and to the vision defining opportunity across our (and other) planets."

Vision defining opportunity. Rockets. Planets. We so miss the space cadet.

(Last July, Oracle deleted Schwartz's old CEO blog where these gems appeared).

Oracle rapidly tried to repair the damage Schwartz had done by bringing Scott McNealy, Sun co-founder and CEO from 1984 to 2006, to the stand. McNealy explained that Sun still thought its IP to be immensely valuable, but didn't want to push too hard. On the stand, Schwartz had rationalised his strategy like this: "We didn’t like it, but we weren’t going to stop it by complaining about it." McNealy clarified that "Open source or open standards doesn't mean 'Let's throw it over the transom. That's a big difference."

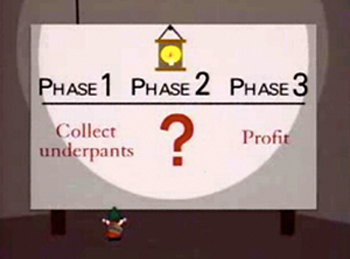

Sun's business plan for open-source software in the 2000s

Schwartz's strategy was to give away the software assets – like Java – in order to drive interest in Sun's high-margin computer hardware. It was accompanied by much hippy-happy-talk: advertising campaigns proclaimed the 'Participation Age'.

This was described as a "Underpants Gnomes strategy" by one pundit and more devastatingly by Dan Lyons, aka Fake Steve Jobs, in one particular post in 2006.

"The more Sun 'wins', the more money it loses. Ponytail Boy has just turned a non-performing asset into a friggin boat anchor," wrote Lyons/FakeSteve. "Why you’ve just turned the entire field of economics on its head! Wow! Did they teach you this at McKinsey?

"Jonathan, this is a hard truth but you have to swallow it: If you’ve got something that for whatever reason nobody is willing to pay you money for, that’s the world’s way of telling you to go do something else. "

If Google needs to jolt the jury into consciousness after all the highly technical talk and complex legal arguments about IP, this would should do the trick admirably. We'll be disappointed if it isn't entered into the docket.

"We probably got a little too aggressive near the end and probably open-sourced too much and tried too hard to appease the community and tried too hard to share," McNealy agreed in 2010, in a fascinating interview with El Reg.

Now you can see why the judge tried so hard to get the sides to agree – and stop the show coming to court. ®