This article is more than 1 year old

Red Hat: Keep clouds open, like Linux

You'd expect Shadowman to say that – again

Red Hat Summit At last year's Red Hat Summit, it was CEO Jim Whitehurst who preached to the open source choir about the need to keep virtualization and the cloudy extensions of it open. And at this year's event in Boston, it was Paul Cormier, president of products at the billion-dollar commercial open source software powerhouse, who banged on the open drum as he and the Red Hat team fleshed out the latest cloudy tools, launched this week.

In the opening keynote, Cormier talked a bit about open, hybrid clouds, and that doesn't mean just mashing up anything and everything and putting a price tag on it. Well, maybe a little.

Red Hat products prez Paul Cormier

When Red Hat talks about clouds, open means using its open source tools: Enterprise Virtualization (RHEV) to slice up physical hardware, the new clustered Storage Server (based on Gluster) to feed VMs and physical machines, and the CloudForms cloud fabric and the OpenShift platform cloud. Red Hat has been talking about the latter two for years now, and they are beginning to come to market.

Open also means supporting VMware's ESXi hypervisor, by far the dominant server slicer in the enterprise, with CloudForms management tools as well as being able to run the entire Red Hat cloud stack and the OpenShift platform cloud on Amazon Web Services' EC2 compute cloud. And don't forget JBoss middleware, please, that's in there, too, in some cases. And of course, it all starts with Enterprise Linux (RHEL) as the guest operating system and the underpinning of clouds.

"Apps run in OSes, despite what some people would have you believe," quipped Cormier. And it is not a coincidence that VMware does not have one of those.

Open means having this stack of Red Hat cloudy code all open source, and it means adopting as many open standards as exist as well as driving them when they don't. VMware can do the latter, but like Microsoft and IBM and Hewlett-Packard and unlike Oracle (ironically enough), VMware will never do the former.

All this talk of openness also means that Red Hat is finally open for business and feels ready to compete with VMware, Microsoft, and any other company that wants to hitch their fortunes to the clouds. And in typical Linux fashion, Cormier explained that Red Hat was going to be able to do cloud and clustered, scalable storage at the fraction of the cost of other suppliers of similar – and often closed source and vendor-developed – software. But money is not the only issue. The complexity is a biggie, which turns into money one way or the other.

"We need to make it simple for our customers to get to the cloud," explained Cormier, stating the obvious but also something that is not trivial given the differences among server hypervisors, cloud fabrics, and other layers in a cloud like their management APIs. To keep it simple, or at least as simple as is reasonably possible, Red Hat has done a number of acquisitions and also rolled new code to create its OpenShift platform cloud, which rolled out this week with pricing and what looks like its final commercial packaging after a year of beta testing. The CloudForms cloud orchestration and self-service portal is also now generally available, Cormier announced.

This year's Summit is also the big coming out party for the Red Hatted version of the Gluster open source clustered file system, which begins shipping now as Red Hat Storage Server 2.0. In the past decade, Linux and x86 servers "really transformed the server market," said Cormier, and now open source clustered file systems running on x86 server iron would do the same thing for the storage racket. In both cases, customers get "more choice, more open, and more capability."

Not so fast, there.

Linux servers represent about 20-ish per cent of revenues, with Windows comprising north of 50 per cent and the remaining 30-ish coming from mainframes, proprietary boxes, and Unix iron. Linux is by no means dominant, but it has become the safe alternative to Unix and the only credible alternative to the ascended Windows, which is about as closed as any operating system has ever been.

The open source community has not taken over the server market by any stretch, and VMware, again proprietary to the core (excepting that Linux kernel it used to have at the heart of the ESXi hypervisor), is by far the juggernaut of x86 server virtualization in the enterprise because it was the safe bet when Windows machines needed to be virtualized and the KVM-based RHEV was not ready for primetime.

And not to pick too many bones, but the server racket has fewer choices today than it did a decade ago, and even fewer compared to two decades ago. There is not more choice, but less.

The good news is, you have a couple of pretty decent choices these days, in Linux and Windows and a few Unixes and a few proprietary platforms that are still kicking. And, by the way, there is no reason to believe that there won't be multiple cloud environments, just like there are multiple operating systems and hypervisors today and there will likely continue to be.

But on the whole, the number of options will be relatively small given the cost of building and supporting these software layers. And there will be incompatibilities, no matter how boldly Red Hat paints its bits with the words "open" and "hybrid."

What is really important is that Red Hat is more open than VMware or Microsoft, and that it continues to deliver enterprise-grade software and support, as it has done for the past decade.

"The world is open. Keep it open. It's up to us," Cormier admonished the crowd at the Summit.

This is a good mantra for Red Hat and perhaps even a good thing for the IT industry to aspire to, but it only reflects a Red Hatter's reality, not the market at large.

The real world of virtualization and clouds is somewhat closed, often incompatible, usually complex, and always costly. It is hard to imagine that the tens of millions of organizations worldwide using Windows will suddenly convert to a Red Hat stack, any more than the reverse is any more likely.

This lofty rhetoric is really aimed at jittery Unix shops, which have the money and the desire to move to cheaper wares, and proprietary systems users, who under normal circumstances might downshift to Unix iron but who might, if budgetary pressures are large enough, go straight to x86 iron and either Windows or Linux.

The more Red Hat can convince customers that it is both more open and cheaper than Windows plus Hyper-V or Windows plus VMware vSphere, the more money it will make. And even then, Unix and mainframe shops are still going to be around a long, long time.

Bundling up

During a press conference later in the day, Brian Stevens, Red Hat's CTO, walk through the OpenShift platform cloud announcements that red Hat actually did this week before the Summit got going.

The OpenShift platform cloud is a stack based on RHEL, RHEV, JBoss, and a bunch of other code (sometimes some components of CloudForms) that Red Hat runs on Amazon's EC2 computer cloud, and it's encouraging application developers to use as they create Java, PHP, Perl, Ruby, Python, Node.js, and other applications wacking MySQL or PostgreSQL databases or the MongoDB NoSQL data store.

"We have to get the developer just back to creating software," explains Stevens, referring to OpenShift, which will be available hosted on EC2 for free for a small setup and for a fee for larger setups, as El Reg already explained in detail. "They don't even know what cloud their software will be deployed on." And they don't, said Stevens, have to care about what software image it is created in or what cloud it is deployed on. They just write their code, compile it, load it, and run it – with autoscaling – on OpenShift, and do the "lather, rinse, and repeat" cycle to iterate that application. Red Hat can take a new set up compiled code and stand it up in about 15 seconds and autoscale it for testing across the OpenShift development cloud.

There will be three different tiers on the public OpenShift cloud, as we walked you through already, but what was not obvious is that in addition to an internally deployable variant of OpenShift, called OpenShift DevOps, which will allow companies to host their own variant of the platform cloud, there will be a variant that will run on a laptop as well so coders can work when they are disconnected from the Internet, called OpenShift Offline.

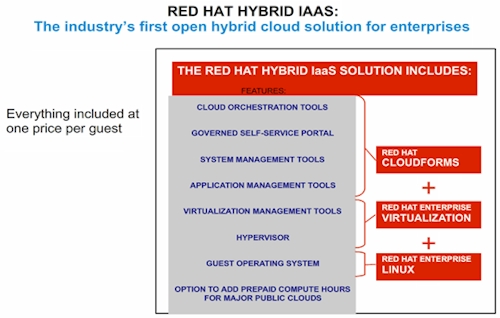

OpenShift makes cloud consumable for developers, and Red Hat has conceded that its packaging and pricing for its various operating systems, hypervisors, and cloud management tools is too complex, and that is why the company has cooked up what it calls the Red Hat Hybrid IaaS.

Red Hat's Hybrid IaaS bundle

This takes RHEL, RHEV, and CloudForms and mashes them all up into a single product with a single order number and a single – and simple – price. RHEL is the guest operating system of choice, of course, and RHEV is the hypervisor layer and virtualization management tool; CloudForms provides a self-service portal for requesting virtual machines stacked with software, orchestrates the provisioning of capacity on private or public clouds, and manages the underlying systems and applications running on this heavenly setup.

This bundle will be available in the summer. Pricing was not provided, but Red Hat will offer this on internal clouds as well as on public clouds, and presumably licenses will be portable in some fashion across the corporate firewall. That's what makes this hybrid.

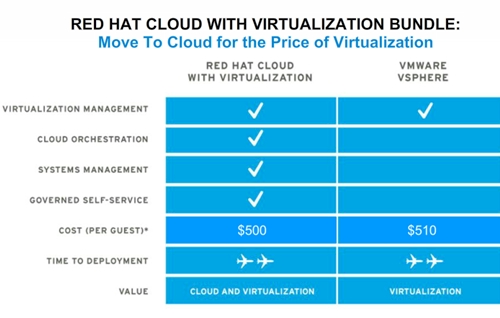

For those just getting started internally on cloud projects, Red Hat has a simpler bundle called the Red Hat Cloud with Virtualization Bundle, which just packages up RHEV and CloudForms together and offers it on a per-VM price.

Red Hat's Cloud Virtualization bundle

This bundle weaves together the RHEV hypervisor and virtualization management tools with the CloudForms cloud fabric and management tools, but does not include licenses to RHEL and does not have the ability to jump out to public clouds. And, it also has a price: $500 per guest VM on the machines you install it on. No counting licenses or cores or any of that.

"We think our customers are going to go right through virtualization to the cloud," says Stevens, adding that only about 10 per cent of RHEL workloads have been virtualized to date because of the "capital efficiency" of RHEL compared to Windows, which is at around a 50 to 60 per cent virtualization rate in the data center, and mostly on VMware's ESXi hypervisor. "You can get the cloud for the price of virtualization."

To back up that claim, Red Hat says that a typical two-socket server can support around eight VMs and if you put VMware's vSphere Enterprise Plus bundle on the machine with three years of 24x7 premium support, that works out to $510 per VM.

The cloud virtualization bundle will also be available this summer. ®