This article is more than 1 year old

Meet the company that wants to destroy Twitter. It's Twitter

Can we build a better FaceTwittle?

For years I've marvelled at Twitter, the most commercially and technically clueless company to ever strike it big. Twitter is now hugely popular and millions of people love to use it. They use it in very creative ways. Twitter's success, in retrospect, now looks blindingly obvious. But Twitter has been uniquely inept at taking advantage of its popularity.

Where do we begin? Twitter's technical ineptitude needs little elaboration. After the official logo, the best known Twitter brand is its out-of-service logo, which has become the global emblem for failure. Right on cue, the service seized up and croaked last week.

Now let's turn to its business acumen.

For the first few years, while a web service is gaining users, it's reasonable to cut it some slack while it figures out what to do. Google actually muddled along for even longer – five years – until borrowing somebody else's idea and finding the right mass market for it. I think astute commenters realised that confidence in Twitter's commercial prowess was misplaced round about here, in July 2009, when a hacker leaked dozens of strategy documents to a sympathetic news site. Of course the "strategy" revealed by all those personal and corporate documents raised more questions than an exam paper.

"Strategy? Don't ask us - we only work here!"

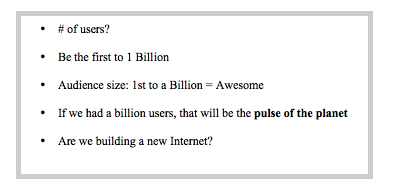

We learned that Twitter wanted to be "the pulse of the planet", but it didn't elaborate on what this meant, or how it might be achieved. The strategy gurus at Twitter must have been so pleased at coming up with this banality, they all went home. Was it going to embed itself with the world's leviathan telcos? Become a gateway? An infrastructure host for applications? Or what?

It's now quite clear what Twitter wants to do. And I can't think of a dumber corporate strategy decision ever.

Could it be Twitter doesn't understand why it's popular?

Twitter wants to be a publishing platform, not a communications network. And not just that, but a one-to-many platform in which the lucky 'ones' are hand-picked. This is not only going to annoy people who like to use it - for short, many-to-many communication - but it also requires a skillset that Twitter has never, ever demonstrated. It's a decision to make anyone doubt whether Twitter itself has even an inkling of why it's popular.

The big idea is to augment the basic messaging particle of Twitter, 140-character tweet, with a proprietary container, called a "card". The cards will host "rich content" - from hand-picked Twitter partners such as New York Times and CNet [soporific content, surely? - ed], and of course advertising.

There's a vestigal hangover from earlier indecisions when Twitter toyed with becoming a platform for applications. The card containers will in the future host applications. But not yet.

So in short, Twitter is deprecating the very thing that made it popular in an attempt to duplicate what lots of other people specialise in doing, to people who get that sort of thing quite happily somewhere else. As the saying goes: "What could possibly go wrong?"

Don't sell US, sell to us

There are some dissenters, and one is Dalton Caldwell, the founder of the ill-fated online media-sharer Imeem. Caldwell has correctly identified the confounding problem with the "internet economy" (sic) today. Real growth is shackled by the absence of markets, of real money changing hands. An "economy" based around web advertising has all kind of unpleasant side-effects, we're now realising. It's the reliance on advertising that drives Google and Facebook to become ever-more rapacious and intrusive in their demands for personal data. And then create ever more inventive sets of inferences from this data, and then package them all up to advertisers, much like subprime mortgage bonds.

Caldwell would rather see people pay real cash into services, and is trying to raise funding for a network "where users and developers come first, not advertisers". The idea, called App.net and originally advanced here, is that Twitter abandoned what it's good at - long before its latest 'Card' caper - and if people pay for their web infrastructure then it stands to prosper. Contrast, if you will, the relative fortunes of Github (which charged, and prospered), with SourceForge (which was reliant on advertising). App.net, which Caldwell says will initially look a lot like Twitter used to, will charge $50 for users and $100 for developer access.

One eternal problem, that predates the web by a few thousand years, isn't going to go away. The new media buzzword "platform" means nothing more fancy than 'wholesale marketplace', and the owners of popular marketplaces have always been tempted to bend things to their advantage. If they're using their marketplace to retail some goods of their own, then problems will ensue, for they immediately come into conflict with their 'partners'. Facebook's predatory attitude to developers today, and Microsoft's in the past, are utterly predictable.

The more immediate problem for Caldwell is the $50 sign-up fee. McKinsey estimates the consumer surplus of web giants giving away their services for free is around €100m a year. In other words, that's what people would be prepared to pay for Flickr, Gmail and Twitter and so on, either directly or indirectly. The web giants don't do this out of benevolence or a love of humanity – although many, including Facebook and Google, pretend to do so. They do so because it excludes competitors and maintains their dominant position in the market. It's a formidable barrier to entry for people like Caldwell.

It isn't insurmountable, however. Both suppliers into the broken supply chain, and end users, long for alternatives. I sketched out what a healthier internet economy could look like in this piece, and will explore some of the opportunities next time. ®