This article is more than 1 year old

Curiosity snapped mid-flight by Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter

Rover reports as ready for duty

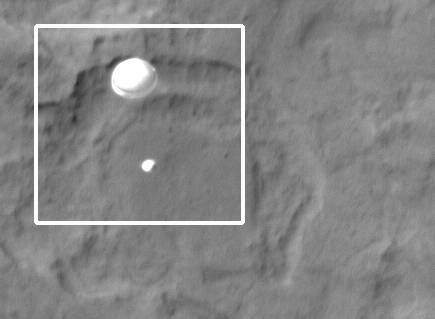

Curiosity Mars mission NASA has released the first photo of the Curiosity rover in flight, after the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter's (MRO) HiRISE camera snapped a shot of the spacecraft parachuting down to the Martian surface.

The MRO was 340km away from Curiosity as its parachute was deployed, slowing the craft from around 900mph to 180mph, before being jettisoned, allowing the craft to land under its own power. The HiRISE camera, which operates at 33cm per pixel, snapped the shot six minutes after the craft's decent into the Martian atmosphere.

Curiosity snapped slowing for landing

At a press conference on Monday NASA engineers said they were slightly shocked by how successful the landing was. Curiosity touched down within a couple of kilometers of its intended position and the Sky Crane assembly lowered the rover to the surface at its intended speed of 0.75 meters per second with just 4cm per second lateral drift. The rover is pointed east-southeast at around 110 degrees, with the front facing down slightly with 3.6 degrees of negative pitch and a two degree lean to the left.

"The landing went really well, so well that we're having to look at the data again to check it's accurate," said Miguel San Martin, the team's chief engineer for guidance and control. "Even in our simulations it never worked that well."

Curiosity is now in nominal mode, meaning it's ready to begin the process of checking and testing its scientific and power systems. With the latest pass of the Mars Odyssey satellite it was able to upload more data, albeit it can only transmit at pitifully slow speeds – bits per second – until it has raised its main antenna. Once the antenna is deployed it should be able to upload a couple of megabytes per second.

Meanwhile, the Sky Crane delivery unit, complete with 140kg of highly toxic hydrazine fuel, headed north immediately after dropping Curiosity onto the surface. The team estimate it would have traveled about 400m away from the rover and then crashed, and due to the nature of the fuel, NASA said it has no plans to take Curiosity anywhere near the crash site.

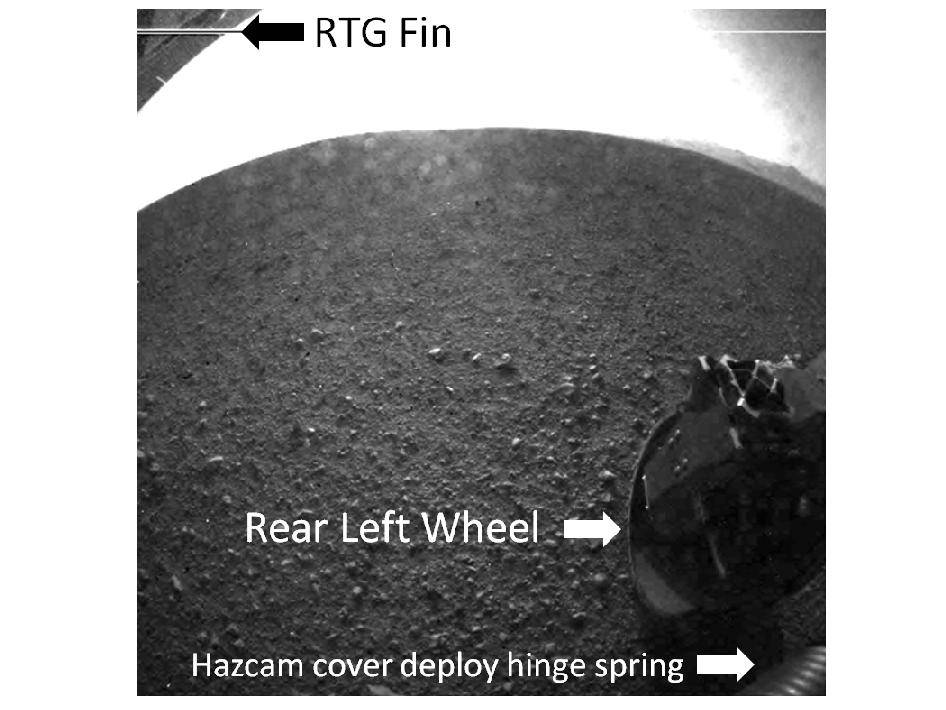

So far Curiosity has sent back four thumbnail images, two sample images of 256x256 and one 512x512 shot from the rear hazcam – cameras designed to watch the rover's wheels and their path ahead and behind. The hazcam shot (below) shows a fisheye lens shot from the back of the rover, with the wheel in the bottom right and a radiator fin in the top left of the picture. Color pictures are expected in two days.

While it's very early days, Curiosity is already collecting data, indeed has been doing so for the whole trip. The rover's Radiation Assessment Detector (RAD) has been operating through the flight to let NASA monitor the potential hazards astronauts making the trip would have to face, and it's also sampling the Martian atmosphere now.

The nuclear heart of the rover is functioning normally. The rover runs on batteries, but these are topped up at night by the craft's radioisotope power system, which uses plutonium-238 to generate around 100w of power via a thermocoupling unit, as well as providing enough heat to keep the rover toasty at night and reduce thermal stressing. This power source is expected to last well past the lifespan of the rover.

In a couple of weeks, after all the checks have been completed, NASA will take Curiosity out for a spin. The team says at first they just want to move the rover a meter or so and then there will follow another round of exhaustive checks before beginning to rove properly.

Round 400 scientists and 300 engineers are now going to start to work on Mars time and will practice working together to control the rover and plot a safe course for it. Once they're comfortable with the craft, and with each other, they will then go back to their stations around the world and start working on the rover's two-year scientific mission.

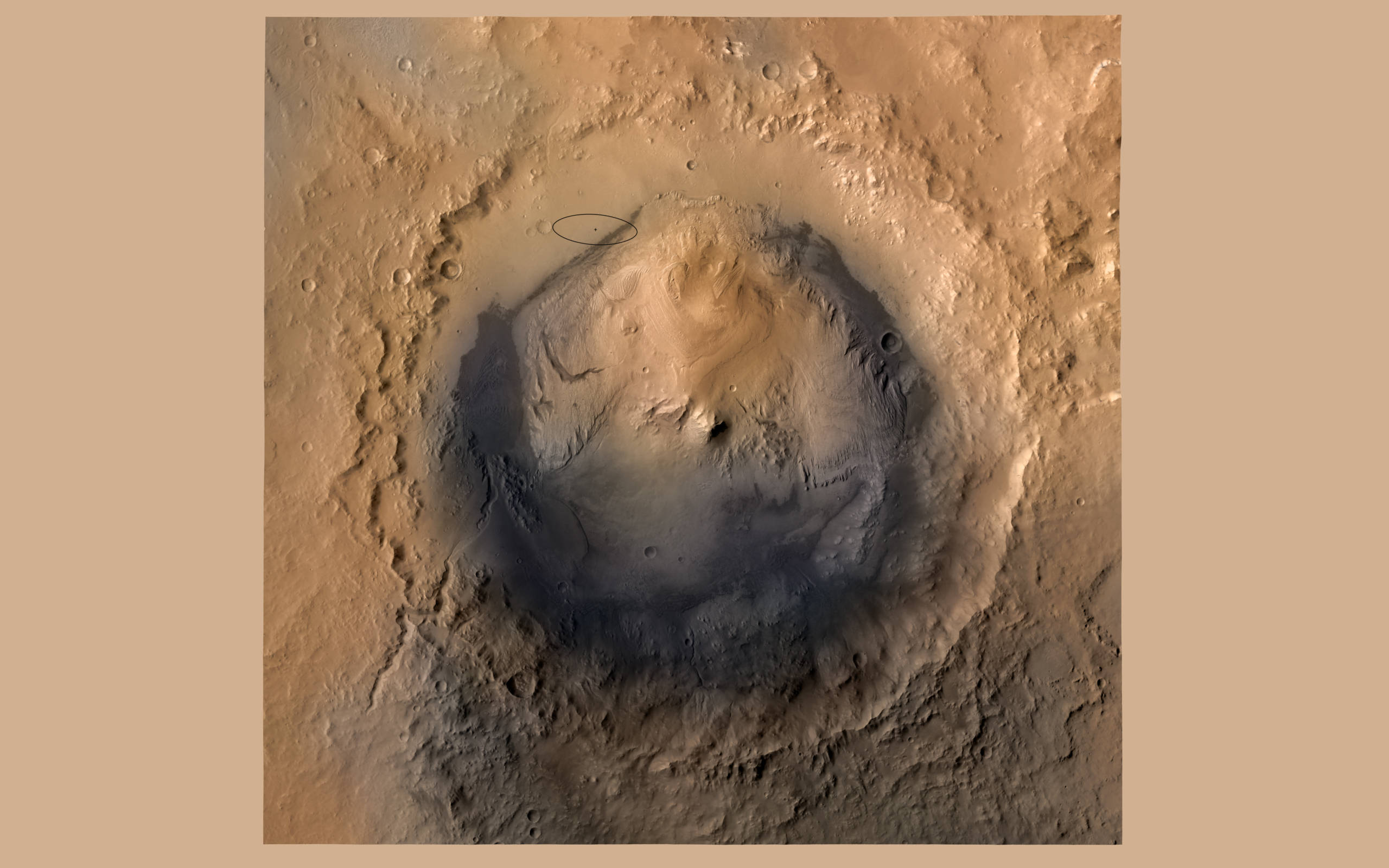

The rover is about one kilometer from a series of dunes that stretch from the north east to the south west of the area around the base of Mount Sharp. The rim of the Gale crater is about 20km from Curiosity and the entire area has been heavily mapped by the MRO to give the drivers the best possible idea of what they are facing.

Project scientist John Grotzinger said that the landing location looks firm, with no wheel sinkage, and the surrounding area shows fairly uniform rock sizes, indicating that the site should be a good sample of Martian soil rather than a site littered with meteorite ejecta. Nevertheless it is exploring an area that is totally new to science.

"We haven't even scratched the surface as yet," he said. "But it's a miracle to us that we were able to choose this place as a result of science. It's a miracle of engineering." ®