This article is more than 1 year old

Bill Gates, Harry Evans and the smearing of a computer legend

Source code of DOS, CP/M diff'ed, expert miffed

The roots of Microsoft's success in using a clone of Gary Kildall's CP/M operating system are well-known and supported by a court ruling five years ago. But that hasn't stopped a software consultant from making claims that could smear Kildall and the late computer pioneer's legacy.

In an astonishing piece published by the IEEE's reputable publication Spectrum, a software consultant called Bob Zeidman claimed to have established "beyond doubt" that Microsoft's MS-DOS was not a derivative work of CP/M.

However Zeidman contrives to ignore the incontrovertible evidence that MS-DOS was derived from CP/M, and instead establishes a straw man. Zeidman, who pictures himself in a deerstalker hat, asserts that he can refute the allegation that "Microsoft stole the CP/M source code" - a claim that has never been made, let alone contested.

Zeidman 's article

Zeidman turns out to be a consultant who developed a tool called CodeSafe, which (like Unix's grep and diff) finds matches in source code files and is plugged several times in the Spectrum piece.

Having used CodeSafe on the source code for CP/M and an early instance of MS-DOS, and found no significant matches, Zeidman declares the job done.

Miscellaneous slurs on Kildall's character, and the origins of his work, are added for good measure.

A quick recap of history

Gary Kildall, a former Intel engineer, created a low-cost operating system that became the standard for personal computers. As such, he's recognised as an innovator, for both the idea and the "business model" were popularised by Kildall and his company, Digital Research Inc.

Kildall died in Monterey, California in 1994. His story is told lucidly and in detail by Sir Harold Evans, the former editor of the Sunday Times, in his book They Made America (2004). Evans had access to a wealth of material not previously disclosed, and his account remains the definitive one. It's also important for a reason that will soon become clear.

In 1980, IBM decided to enter the personal computer market in a move code named Project Chess. The obvious choice of operating system was the industry standard: Digital Research's CP/M. CP/M ran on hundreds of hardware configurations, and sold millions of copies. It had created the market for low-cost third-party packaged software. One of the companies selling packaged software, Microsoft, marketed a BASIC programming language and employed about 30 people. Reflecting the anarchic DIY spirit of the early microcomputer industry, dozens of companies sold systems using cloned CP/M software, but US copyright had only just been extended to cover software, and no court had yet considered a test case. IBM had already decided on an Intel processor at the heart of its first personal computer, the IBM PC.

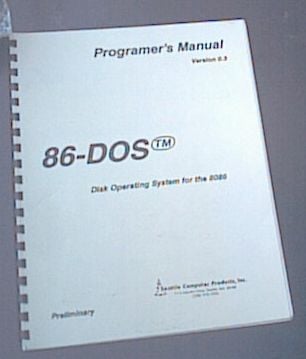

In a famous piece of opportunism, Gates offered to license IBM an operating system in addition to Microsoft BASIC. He didn't have one to sell them, and acquired a system from one of the cloners, Seattle Computer Products. SCP had beaten Digital Research to market with an Intel 8086-compatible CP/M clone called QDOS (for "Quick and Dirty Operating System"). QDOS was developed by an engineer called Tim Paterson, for use with computers fitted with an add-in board powered by the Intel processor family.

Without revealing the reason for his acquisition, Gates snapped up QDOS, which had been renamed 86-DOS, and licensed it to IBM, which would later sell it with the first IBM PC in August 1981.

What is the evidence, then, that QDOS was a derivative work – a rip-off? The answer lies in the API, which describes how software can call up the underlying operating system and make it work for the user.

The first 26 system calls of MS-DOS 1.0 are identical to the first 26 system calls of CP/M. A few of the API names, accessed through CP/M's int 21h mechanism, were altered – CP/M's "Sequential Read" became MS-DOS's "Read Sequential" but the order was preserved. Paterson has always denied using Digital Research source code to create QDOS.

“I never looked at Kildall’s code, just his manual,” Paterson told James Wallace and Jim Erickson, authors of the 1993 biography of Gates, Hard Drive.

Paterson has admitted using Digital Research's DDT debugger to explore the internals of CP/M.

Priced out of the market

IBM did not appear to be aware of the ancestry of the OS it had licensed from Microsoft, and legal considerations gave Digital Research some leverage to stick its nose in. IBM agreed to license and sell CP/M alongside DOS on the new IBM PC. However, when the IBM PC went on sale, DOS diskettes were bundled in the box, or available for $40, while a voucher entitled the buyer to acquire CP/M for $240. IBM's pricing excluded CP/M from the market. Digital Research appeared to have had a case for infringement, but declined to file suit. The market would explode after IBM's launch of the PC, and Digital Research was growing with it.

According to John Wharton, the Intel engineer tasked with doing the technical valuation of QDOS in 1980, QDOS certainly lived up to its name: just 27 of CP/M's 37 calls were supported, and some cosmetic changes had been made, the best known of which is the command prompt separator. QDOS also used a different file system to CP/M, its own one.

After the saga was published in Sir Harold's They Made America, Paterson filed a defamation lawsuit, Paterson v Little, Brown & Co, against Sir Harry in Seattle, claiming the book's assertions had caused him "great pain and mental anguish". The court heard the detailed API evidence, and rejected Paterson's suit in 2007. US federal Judge Thomas Zilly observed that Evans' description of Paterson's software as a "rip-off" was negative, but not necessarily defamatory, and said the technical evidence justified Sir Harry's characterisation of QDOS as a "rip-off". Evans had his facts right, the judge pointed out, and in the US, this is an absolute defence to defamation claims.

Knowing this, we can review Zeidman's claims published by Spectrum magazine in a better perspective.

"Until now there’s been no way to conduct a reliable examination of the software itself, to look inside MS-DOS for the fingerprints of CP/M, and settle the issue once and for all," he claims. But no such examination is required. The verdict of the Paterson lawsuit has been publicly available (on the Seattle Post-Intelligencer newspaper's website) for four years.

"If [Kildall] was not as successful as Bill Gates, it wasn’t because Microsoft stole the CP/M source code," concludes Zeidman. But nobody has ever made such a claim: not even Paterson.

"My company’s CodeSuite forensic software lets us look inside operating systems and other software for fingerprints of other programs," boasts Zeidman. In this particular case, by fingerprint he means scraps of text in the MS-DOS and CP/M source code and assembled binaries. Where a fingerprint exists in both products, Zeidman seems utterly baffled because there just isn't enough to piece together a smoking gun.

Kildall had reportedly stashed a secret command in CP/M to identify (and shame) cloners, who wouldn't have implemented the secret feature unless they found it or had seen the source code.

Zeidman can't find that hidden cookie in MS-DOS with his ASCII-matching tool, presumably because there's no "SECRET COMMAND HERE" line to search for. But we know from Paterson's own evidence that the QDOS author didn't copy the source code, but did implement the same APIs so that libraries of software remained compatible with the two rival systems.

"It is difficult to imagine [Kildall] could squeeze in an undetectable encryption routine," waffles the self-styled computer forensic expert.

The IEEE is the professional association for American engineers. With the publication of this article, it has not only managed to smear the reputation of one of the computer industry's greatest pioneers, but also insult the intelligence of its readers. ®