This article is more than 1 year old

WTF is... RF-MEMS?

Apparently, a way to make smartphones much, much better phones

Feature Smartphones nowadays come with big screens, megapixel-packed cameras and, thanks to apps, many, many more features than anyone could have dreamed of in the early days of mobile telephony. It has even reached the stage where making telephone calls is just one small part of a modern phone. And yet the need to support all the radio technologies punters expect to be able to use, for voice and for data, ensures that wireless communications is still the hardest part of a phone’s design to get right.

Just ask the guys who worked on the iPhone 4...

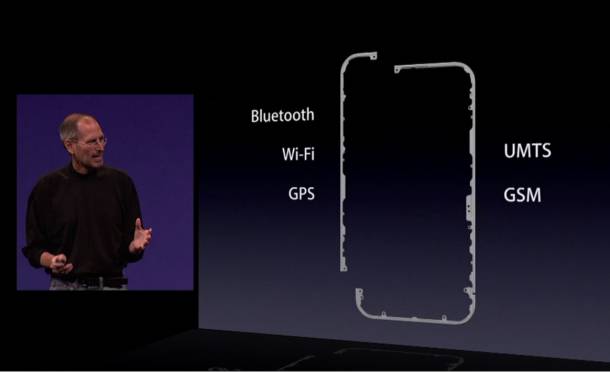

Steve Jobs explains Apple's grip-of-death iPhone 4 antenna design

That was in 2010. Today, more than two years later, your typical smartphone is even more complex, wirelessly speaking. A 2012 handset might be expected to feature Wi-Fi in two different bands: 2.4GHz and 5GHz. Bluetooth too, in the 2.4GHz band. Then there’s 4G LTE for fast data communications and 3G for voice - because 4G can’t yet do voice properly - and for data in places where 4G hasn’t been rolled out yet. Just in case the user roams into a region without 3G either, phones still have to support 2G. All this cellular goodness has to work across a range of frequency bands to support different carriers in different countries.

Oh, and don’t forget there’s more wireless goodness coming. Devices are soon going to have to start supporting 60GHz short-range, high-speed data transfer communications if they’re to continue offering the full 802.11 standard. WiGig - aka Wireless Gigabit - builds on the agreed 802.11ad 60GHz specification and it’s coming in 2013-2014, trailing new pick-up specifications in its wake.

To get the promised ever higher data transfer rates, devices need to stick to these newer radio specifications very closely. Old, broad tolerances which might have been acceptable in the GSM and GPRS days will no longer do. That means more effort needs to be put in to get each antenna turned correctly from the off.

To make it all work, today’s smartphones need multiple, pre-tuned antennae and a host of different chips to manage the signals for each of these technologies. And they all have to fit within the phone’s casing. No one, after all, wants to go back to extendible external aerials.

Were punters happy with ever-fatter phones, that would be much less of an engineering problem than it is, but they’re not - they want thin, pocket-friendly devices.

The solution might seem obvious: build in a single, universal radio able to hop across all those radio technologies and frequencies at will. It’s an answer that’s easy to state, rather harder to realise.

Back in September 2011, Samsung released a Windows Phone smartphone, the Focus Flash, which featured a little-known first: it contained a radio frequency micro-electromechanical system (RF-MEMS). This tiny chip, developed by WiSpry, a company based in Irvine, California, was capable of physically changing its impedance under the influence of a software. The upshot: it could be used to dynamically tune the Focus Flash’s antenna to meet the needs of some if not all of the radio technologies the phone uses.

WiSpry has been working on RF-MEMS chips for more than ten years. Indeed, MEMS makers have been shipping these kinds of chips since the middle of the last decade. Getting them to work with mobile phones has long been a goal, but it’s proved hard to attain. While phones were chunky and could be stuffed with all the antennae they needed, there wasn’t much need to implement RF-MEMS in handsets. There were fewer radio technologies to support too.