This article is more than 1 year old

Curiosity finds organics on Mars, but possibly not of Mars

Mission director vows to hold his tongue in future

NASA says that no, it hasn't found definite proof that Mars has its own organic compounds, but that it has found some very interesting indications that need to be checked.

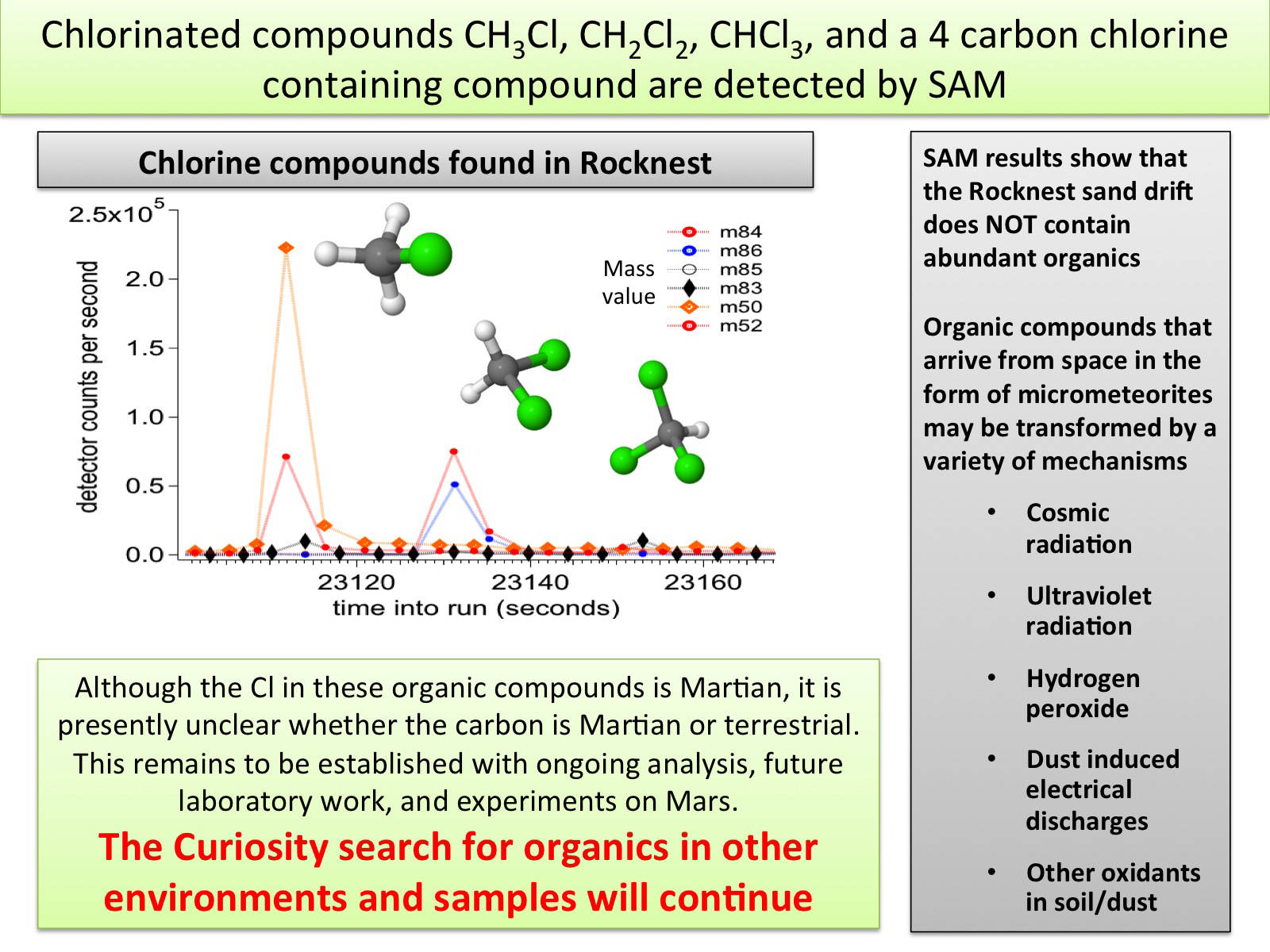

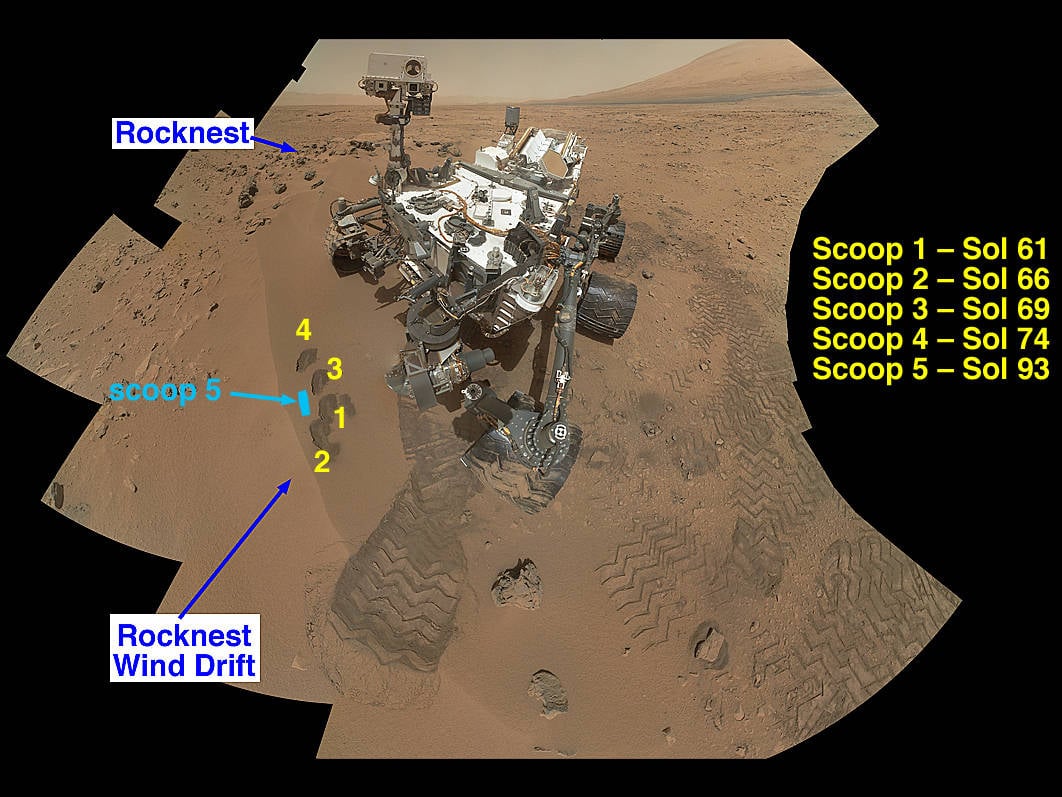

At a press conference on Monday morning at a meeting of the American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco, NASA said that so far Curiosity's Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) tool has taken five scoops from the Rocksnest sand dune and analyzed them using the rover's Chemistry and Mineralogy (CheMin) instrument. In those samples it found a significant amount of water vapor and a range of chlorinated hydrocarbons that might suggest the discovery of organics, but they're far from claiming definitive proof.

"SAM is working perfectly well and it has made a detection of organic compounds, but we don't know if they are native to Mars or not," said Curiosity project scientist John Grotzinger. "Curiosity's middle name is patience, and we all have to have a healthy dose of that."

To begin, the team is checking to make sure that the substances detected aren't a case of sample contamination from Earth, like the plastic found by the rover. Another possibility is that they arrived from comets of meteorites that fell on the Martian soil.

Another explanation is that the hydrocarbons were possibly formed in the heating process the sample underwent for testing. It'll be a long time before anyone at NASA might be ready to confirm the existence of native Martian organics.

A chance comment to a journalist by Grotzinger last month caused a welter of speculation that native organic compounds had been found. Such was the fuss that NASA was forced to release a statement denying this, and Grotzinger said that the overall enthusiasm of the science team at getting good baseline sampling of Martian soil was the cause for the initial excitement.

"What I've learned from this is that you have to be more careful about what you say and how you say it," Grotzinger told the assembled press on Monday. "We're doing science at the speed of science and the world's moving at the speed of an Instagram."

Although there's no definitive proof of homegrown Martian organics, the analysis so far does pose some interesting questions. For example, the water samples tested shows that Martian water has five times the level of deuterium – a heavy hydrogen isotope – than is found in seawater here on Earth. This could be because the Marian atmosphere is losing lighter isotopes, something the MAVEN probe will test when it gets to Mars orbit in 2014.

The soil sampling so far has also shown that Curiosity's instruments are functioning normally and have been testing base Martian material, since a close correlation has been found between soil the rover has sampled and that tested by its predecessors Spirit and Opportunity. Ralf Gellert, principal investigator of Curiosity's Alpha Particle X-Ray Spectrometer, said this was in part deliberate to try and find what the everyday surface of the Red Planet was made of.

There was some understandable disappointment among the assembled press at Monday's conference, including with this hack. But we really should get over ourselves and remember that this entire mission is historic. NASA has lowered a nuclear-powered, laser-wielding, 1.5-ton rover onto the Martian surface using a delicate hovering-rocket descent stage, a rolling laboratory that should provide years of useful science.

The fact we can't get a quick fix of results says a lot about the strengths of NASA's careful scientific methodology, and a lot more about humanity's weakness for a good story. ®