This article is more than 1 year old

Making MACH 1: Can we build a cranial computer today?

How SF gets it right by getting it (mostly) wrong

Monitor is an occasional column written at the crossroads where the arts, popular culture and technology intersect. Here, we look back at 2000AD's MACH 1 - the first secret agent with his own, in-body computer.

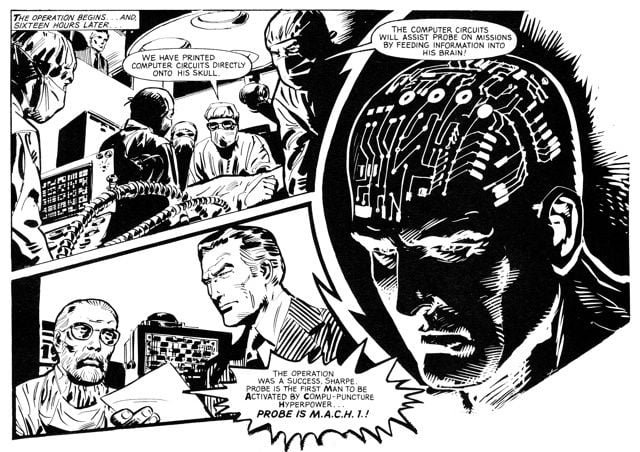

In 1977, Pat Mills, the first Editor of 2000AD comic, created MACH 1, a strip telling the story of John Probe, a super-powered cross between James Bond and the Six Million Dollar Man. These days, most fans of the strip remember the Man Activated by Compu-puncture Hyperpower for his enhanced, bionic-level strength, but Probe had another McGuffin: a computer grafted onto his skull.

Probe’s up-close-and-personal computer - known affectionately as ‘Computer’ - could hear the secret agent ask it questions and was programmed to respond with mission-relevant information.

Back in the late 1970s, this was pure sci-fi. There were desktop computers in the States, and they were starting to appear over here, but the idea that any of 2000AD’s readers would have one of their own, let along one small enough to fit inside the human body, was fanciful in the extreme.

And yet four of five years later, thanks to Sinclair, Acorn, Commodore, Dragon and co., many Earthlets did indeed own a computer at home. Now, almost 36 years on, as gadgets from the smartphones we all have in our pockets to the likes of the Raspberry Pi demonstrate, computing power can now be placed in a very small space indeed.

So could we create a MACH man’s cranial computer today?

It’s not beyond the bounds of possibility. Probe’s computer could speak and hear. Speech synthesis is a doddle to do, and if the output is fed through a tiny speaker tuned to a frequency that will make the user’s earbones resonate - a technique that’s been applied to audio output since the late 1970s - our modern day MACH man would be the only one able to hear it. Fit a tiny microphone into his voicebox and he’d be able to answer back, speech recognition software doing the hard work.

The circuits of Probe’s computer were applied directly to his skull. In at a time before World+Dog knew what a silicon chip was, 2000AD’s artists envisioned the computer as being comprised of electrical lines and bulk components. Laying down layers of flat copper circuitry onto the curved surface of the skull would be tricky, but not impossible. CAT scans would allow a precise model of the subject’s head to be prepared. The circuitry could be fitted to that before being placed on the real skull.

Getting the chips in place would be harder, not to mention leave a series of bumps and lumps under the skin. But it’s not hard to envisage removing an area of bone during surgery and replacing it with a 3D-printed unit containing circuitry, memory, solid-state storage, processor and I/O. Hook it up to the aforementioned mic and Bonefone-style resonator, and you’re away.

Well, almost. We still need power. How about a wee - and well-sealed - thin lithium polymer battery kept topped up by a gadget for converting kinetic energy from our MACH man’s movements into electricity? You know, the kind of rig that keeps watch springs tightened. Such a system was proposed for phones and music players a couple of years back.

Of course, this being a lithium battery, our hero’s bosses in the SIS - modern day equivalent of the slimy, xenophobic Dennis Sharpe - would need to ensure the power pack can be eventually removed and replaced. That said, given the kind of scrapes the original MACH 1 got into, perhaps his non-hyperpowered successor wouldn’t last long enough to need a new battery. Assorted off-the-shelf bio-sensors would allow the computer to track the state of MACH 2013’s physiology.