This article is more than 1 year old

Infinite loop: the Sinclair ZX Microdrive story

The rise and fall of a 'revolutionary' storage technology

Inside the Microdrive

Both Southward and Cheese were based at Sinclair Research’s facility in The Mill, St Ives, Cambridgeshire. In a Sinclair staff guide of 1982, Cheese is described as “currently designing the Micro Floppy electronics”. Meanwhile, over at Sinclair’s King’s Parade office in Cambridge, the company’s industrial designer, Rick Dickinson, worked on the look of the drives and the cartridges.

Dickinson, who in 1986 left Sinclair to establish his own design agency, which he is still running today, says the look of the Microdrive came directly from the Spectrum itself, the unit replicating the computer’s plastic casing with its distinctive raised rear section - there to make room for the TV modulator in the case of the computer - and even featuring a black-painted aluminium upper faceplate, as per the Spectrum. There, the metal sheet covered the rubber intra-key areas of the keyboard; on the Microdrive it was there simply for the look. As for the cartridges, says Dickinson, “once you’ve got a place for the exposed tape, a grip for when it’s being removed from the drive, a place for a label and a small case to keep it in, it’s pretty much designed itself”.

Ben Cheese in Sinclair's 1982 Staff List

The ZX Interface 1, which would connect the Microdrive to the Spectrum, was engineered by Martin Brennan, who would go on to work on Atari’s Jaguar console and, in the past decade, to design and market the Brennan JB7 digital music storage and player system. Brennan designed the Interface 1’s electronics and produced the unit’s Rom chip, writing its networking code himself. The mechanical design was handled by John Williams.

Brennan came to Sinclair Research in late 1982, having been offered an open-ended engineering role with an emphasis on artificial intelligence design by Nigel Searle on the back of his work on games software. Brennan today recalls becoming involved in the Microdrive project because, on his arrival at Sinclair, he was keen to see one of the promised ‘revolutionary’ drives and asked if he could. This was seven or eight months after the drive had been announced. It became immediately clear to him that there was still a lot of work to do. “The mechanical design had been done, as had the industrial design, by Rick Dickinson,” he remembers. “But almost nothing had been done on the electronics side and nothing on the software.” Brennan took on these tasks.

Ian Logan, a Lincolnshire-based freelance coder, author and medical doctor, was commissioned to write the extra Basic commands Spectrum users would enter to operate the Microdrive. These were built into the Interface 1’s 8KB Rom chip and patched onto the Spectrum Basic Rom when the Interface was plugged in. Bug fixes for the Spectrum Rom were added too.

Wanted: Spectrum Rom expert

Logan’s involvement arose from his work disassembling the Spectrum Rom, an effort he detailed in a hugely selling book of the time, The Complete Spectrum Rom Disassembly, which he co-authored with Frank O'Hara. Logan went through the computer’s firmware, detailing routines, jump table locations and such. The result was a reference not only much in demand among would-be machine code writers - Sinclair didn’t offer such a detailed reference itself - but with Sinclair staffers too, Martin Brennan recalls.

The Spectrum Rom had been developed by Steve Vickers on behalf of Nine Tiles, the software developed commissioned by Sinclair to produce the Spectrum’s Basic interpreter and operating system. Vickers left Nine Tiles in May 1982. Spectrum hardware designer and Sinclair employee Richard Altwasser had gone too, to join Vickers to develop a computer of their own, the Jupiter Ace. According to Brennan, they left behind all the machine code print-outs and source code listings you could want, but without them there was no one at Sinclair who knew the software intimately - the sort of people who could be called on to help tie together the Spectrum’s code to that needed by the Interface 1 and the Microdrive.

Enter, then, Ian Logan, whose work had given him that knowledge. Logan pinpointed three memory addresses Brennan could use as a jumping off point to intercept the Spectrum’s Basic interpreter and redirect the computer’s program counter to the Interface 1 Rom and the Basic commands it added.

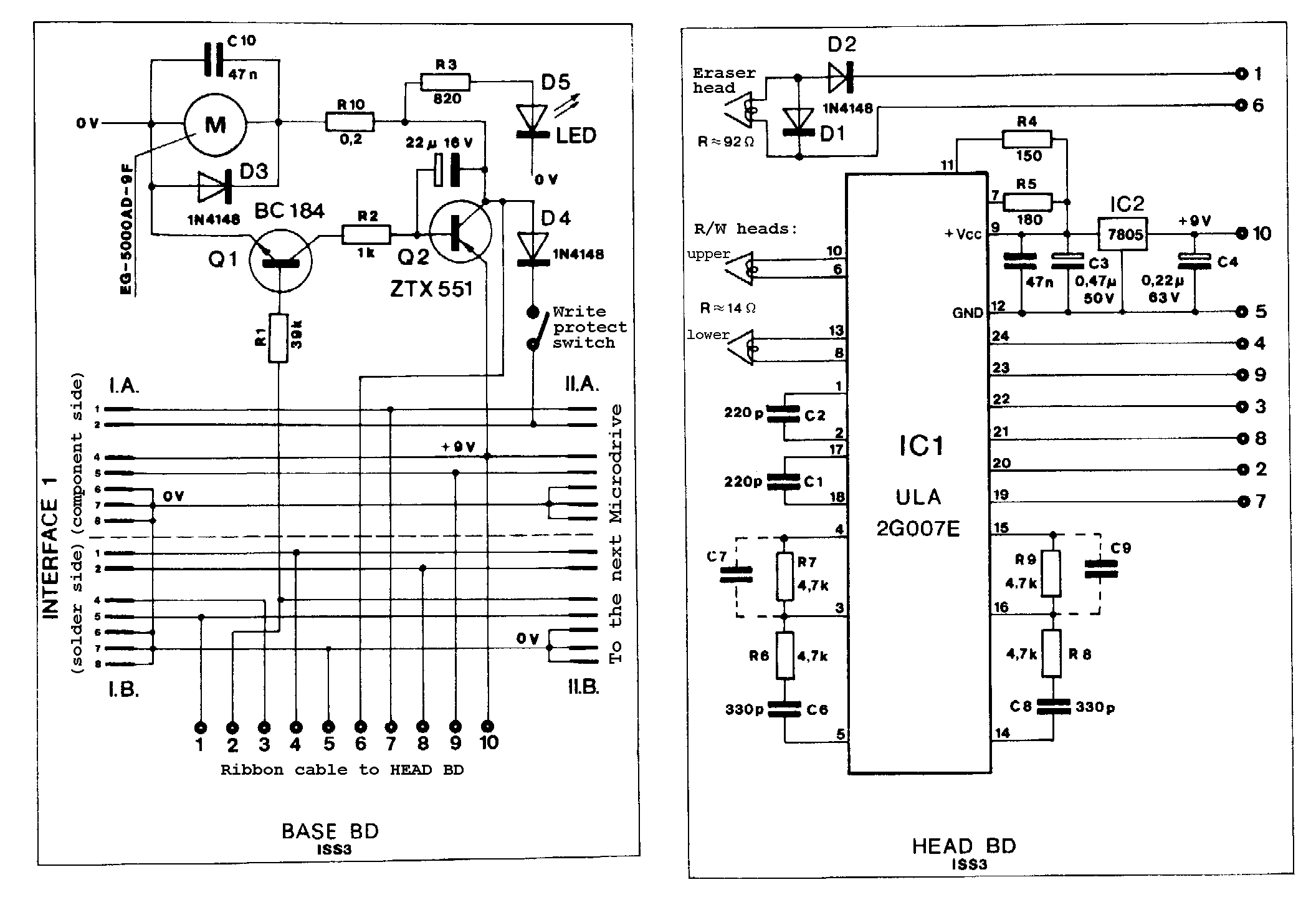

Speaking to Sinclair User magazine after the launch of the Microdrive, Logan said of the peripheral: “It was developed in a large crate with the ULA at the centre. There is very little to the insides of the Microdrive. There is one ULA and the dual heads which read the tape. The Microdrive program was developed on EPROM. If there were corrections to the program I would go to Cambridge with the alterations and we would blow a new EPROM. In the end, Martin Brennan, who was in charge of the project, said ‘Right, that’s the end’. I have no doubt that he added two extra things by the next morning.”

The ULA was designed by Ben Cheese, the internal mechanics by John Williams. Jim Westwood provided guidance on how the Microdrive should be handled in Basic.

Logan revealed that the initial 100-odd Microdrives all went out with EPROM chips, to allow them to be updated with new code because, as he put it, “Sinclair Research wants to redesign the circuit board at some stage”. Burning a final Rom would take place, he hoped, when at least two bugs in the then-current code had been squashed.

It quickly emerged that there were other problems too. While many reviewers were generally positive about the Microdrive - the speed was the main issue; it wasn’t really quick enough to be a floppy killer - only regular usage would reveal the design’s weak spots.