This article is more than 1 year old

HP's 'historic' Project Moonshot servers aim at hyperscale future

First Atom nodes, then ARM and others to 'change the server market'

HP didn't invent the rack-server business, but Compaq – the company it acquired more than a decade ago – did. HP can't buy its way into the next system era, which is why it is trying to create that era itself with its second-generation Project Moonshot servers.

The initial "Redstone" Moonshot boxes were development machines based on Calxeda's ECX-1000 ARM-based processors, and the company has had over 50 customers kicking the tires on these. The "Gemini" Moonshot machines launched on Monday are intended to be used as production machines, with initial server nodes based on Intel's "Centerton" dual-core Atom S1200 series chips. Other x86 chips from AMD, plus ARM processors from Calxeda, Texas Instruments, and Applied Micro Circuits are also expected to be used in coming months.

For companies with modest data processing needs, there is nothing wrong with a ProLiant server or any of its competitors in rack or tower form factors. But companies building managed hosting operations or virtualized clouds have scalability, cost, power, and cooling issues that a modest IT operation just doesn't have to worry about in its data closet. And as the homegrown server crowd, which have massively scaled applications that span hundreds of thousands to millions of servers, knows so well, a new application architecture and the need for higher efficiency and lower cost is driving all of the extra goodies out of servers.

The large hyperscale data center operators of the world are estimated to buy something on the order of a fifth of the servers shipped each year. Just like supercomputer technology set the stage for what commercial computing would eventually look like, these cloudy apps and their underlying minimalist architecture might be a preview of what a typical data center will look like a decade from now.

Dense, minimalist designs tuned to specific workloads are becoming more normal, and companies such as Google, Facebook, and Amazon are building their own machines, while others are going to Dell, HP, Quanta, and others to get custom iron that fits their workload down to the last bit. A $6,000 two-socket x86 server that eats up 1U or 2U of rack space just doesn't cut it anymore for these customers, and in the years ahead it probably won't cut it for the rest of us either.

"Right now, we are on a path that is not sustainable from a space, energy, and cost perspective," explained HP CEO Meg Whitman in a canned presentation that kicked off the Moonshot launch.

Whitman said that hyperscale data centers, driving the next 20 billion devices to be linked to the data center, will require somewhere on the order of 8 to 10 million new servers in the next three years. Using conventional rack or blade servers, those servers would take up around 200 football fields – about the 13.5-mile length of Manhattan. And those data centers will cost on the order of $10bn to $20bn, she said, and would require approximately ten power plants to juice them up – about the equivalent of two million American households.

"So clearly, something needs to be done," she said.

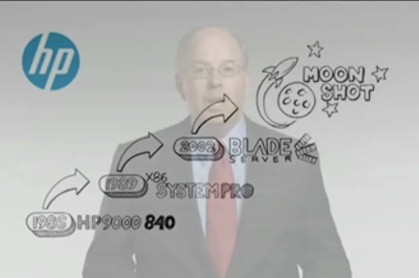

The history of HP server innovation according to Enterprise Group GM Dave Donatelli

And that something, according to HP, is its new Moonshot system, which will bring together modest and power-efficient computing elements on "cartridges" that snap into a chassis backplane using what looks like PCI-Express slots, along with storage blades and integrated switch modules to create a data-center-in-a-box.

Dave Donatelli, general manager of HP's Enterprise Group, said in the Moonshot launch webcast that many of the largest cloud operators have over one million servers today, that financial services companies have tens of thousands of servers, and that it would not be hard to imagine clusters of hundreds of thousands of servers in this big-data world.

The HP Moonshot Gemini 1500 server chassis

"One thing you can count on is that no one will want less computing power or data storage in the future," said Donatelli. "The problem is that the client/server architecture that we have had since the 1980s was not built to handle this level of computing. And you just can't make a few tweaks to the design and make the problems go away. For this level of computing, you need to dramatically rethink, in every way, how servers are built."

That is precisely what Google and Amazon have been doing secretly for years, and what Facebook and now Rackspace Hosting are doing out in the open through the Open Compute Project.

And while HP did not talk about Open Compute or the fact that its Moonshot designs are not compatible with the Facebook & Friends server and rack designs, Moonshot is absolutely about blunting the uptake of Open Compute machinery (generally built by Quanta, Wiwynn, Hive Solutions, and others) while adopting some of the same minimalist ideas.

The initial Moonshot machines look to be based on fairly wimpy-cored Atom and ARM processors, but there is every chance that in the long run HP will put beefier Xeon and Opteron processors in the Moonshot chassis. (El Reg will be following up with HP about this shortly.)

The initial Moonshot 1500 server chassis is an oddball 4.3 rack units high, so to get ten of these in a rack you need to move to a non-standard rack (in terms of height, not width). The Open Rack design is also a non-standard form factor, being wide enough so you can get five 3.5-inch drives across the front of a server chassis. The Moonshot 1500 chassis has three rows of 15 server cartridges that snap into the backplane, with two Ethernet switch modules that snap into the length of the chassis.

The first Moonshot server nodes are, as expected, based on Intel's dual-core Atom S1200 processors, but Donatelli said in his presentation that AMD, Texas Instruments, Calxeda, and Applied Micro Cicruits would work with HP to get their chips onto Gemini server cartridges. No time frame was given for this, but considering that they have had nearly a year and a half to build server nodes, you would think they would be ready today.

El Reg expects that HP has worked out a deal to let Intel go first, and that HP wanted to be ready with the Gemini machines last December when Intel got the Centerton Atoms out the door. That would have meant a spring-ish launch for other x86 and ARM processors, which is right about now.

A Gemini server node based on Intel's Atom S1200

The Atom-based Gemini server node has an Atom S1260 processor running at 2GHz with 1MB of L2 cache memory. That chip has 64-bit processing and memory addressing, plus VT support for hypervisors, ECC memory scrubbing, and HyperThreading to give you two threads per core. The S1200 also has a PCI-Express 2.0 peripheral controller and a DDR3 memory controller that allows up to 8GB to be configured to the node. The node has one memory slot and one 2.5-inch drive bay.

HP says that the Moonshot design will hold up to 1,800 unique server nodes per rack, and if you do the math that means ten of the Moonshot 1500 enclosures and four server nodes per cartridge.

HP is shipping the Moonshot machines in the US and Canada right now, and will be rolling them out to the rest of the world and through the HP server channel next month. A chassis loaded up with 45 Atom S1200 nodes, each with 8GB of memory and a 500GB SATA drive, plus one switch module, costs $61,875. HP is not breaking down the prices for the chassis, nodes, and switch.

HP is trying to get its beleaguered employees and channel partners to fired up about Moonshot, as if this is something that can transform HP and its systems business. That's what Donatelli, who is in charge of HP's systems, wants to believe, and so does his boss CEO Whitman.

"If you look at the history here," explained Donatelli, "when HP invented the x86 server, most people back in that time – which was 24 years ago – said 'Who the heck would use this to go run their business on?' Now we know it is the predominant way that people do their computing. We think today is one of those historic days. We're going to look back ten years from now and say that this was the day, again, that the server market changed. They'll look at a picture of this, and they will laugh at our suits and ties, and say we are out of style, but this is the day it changed."

HP, of course, did not invent the x86 server business. And neither did it invent the hyperscale server business – Google did. But this time around, at least HP is trying to build the new systems business itself, not waiting to buy a company that has already done the work. That's encouraging, even if it should have been done years ago.

Change is difficult and risky, which is why big public companies resist it as long as they can. ®