This article is more than 1 year old

Sord drawn: The story of the M5 micro

The 1983 Japanese home computer that tried to cut it in the UK

Sord in a gunfight

Not buying British became even easier in July when Sord knocked £40 off the M5's price, taking the cost of the new micro back to the originally promised £149.95. Peeved punters who’d already spent £189.95 would be sent a copy of the games-oriented Basic G Rom cartridge in compensation, said Sord. It had had little choice but to make the M5 cheaper. In previous months, Sinclair, Commodore and Oric had cut their prices - a major battle was brewing.

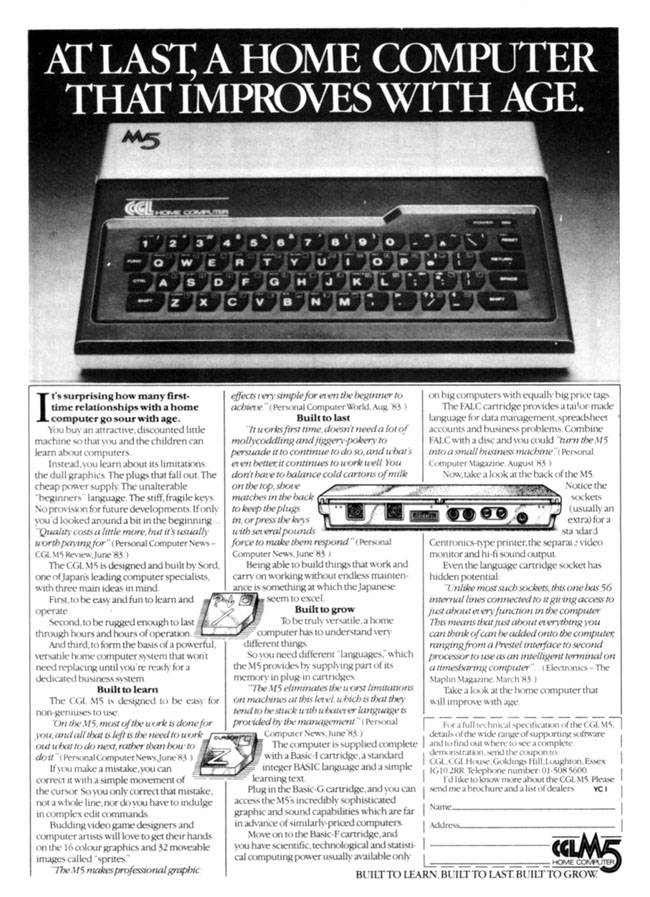

One, it seems, that Sord was no longer quite so keen to fight. By November 1983, and possibly much earlier, the M5 was being released not under the Sord brand but as the ‘CGL M5’, the machine’s first UK distributor now handling all aspects of its sale and support in Britain. As CGL had suggested before, Sord wanted to focus its attention on other, more business-centric machines, and it appears to have decided to step away from the M5 when it released its $2000 M23P business luggable in the US in August 1983, along with a $5000 Motorola 68000- and Z80A-equipped desktop, the M68.

The truth was that its small headline memory size made the M5 less appealing than the 16KB, 32KB and 48KB computers it was being sold against. True, they too had less usable memory than their totals suggested, a lot of Ram being reserved for the video buffer and system usage, but in buyers’ minds it made the 4KB M5 less attractive. No wonder CGL’s adverts played down the M5’s spec. More experienced users scoffed at the cut-down Basic I bundled with the machine and the extra £35 needed for the graphically rich, but still lacking floating maths alternative, Basic G. If you wanted floating point maths, you’d be needing the Basic F cartridge, sir.

As Max Phillips, writing in Personal Computer News put it: “There is only one major complaint: Basic G should come with the M5. You can’t disguise the price of the machine just by packaging it with a crude Basic and hoping people won’t notice the extra £35.”

That was the situation in the UK. In Japan, Sord now faced the emergence of the MSX standard, a Microsoft-led scheme that was backed by the major Japanese electronics companies and which defined a home micro specification designed to ensure software compatibility between hardware from different suppliers - a home version of what later transpired in the business PC market. The M5 Turbo and the M2 mentioned at the UK launch do appear to have been released in Japan - as the M5 Pro and the M5 Junior, respectively - but they never made it over here.

Meanwhile, Sord was suffering what co-founder and President Takayoshi Shiina would later call an “an orchestrated smear campaign” which, he alleged, involved the deliberate spread of rumours claiming the company was financially sick. Shiina denies that was the case, and told Computing Japan magazine in 1994 that the it all began in February 1983 after “the president of a famous company called me and asked me to sell him my company”. Despite the unnamed executive’s “persistence”, Shiina refused to throw in the towel.

“Then, in the following months, some really strange things started happening,” he said. “Suddenly, for no reason I could track down, the delivery of parts would stop. And the leasing companies decided not to extend credit to our customers any more.”

Sord never brought to the UK the other machines it promised would ship after the M5. Back home in Japan, the company became increasingly interested in mobile computing, having released the 4MHz Z80A-based, 9kg M23P that Summer. Sord followed it up a year later with the handheld machine it had previously promised would ship in September 1983. The IS-11 - aka “The Consultant” - was a $995 A4-sized machine based on a 3.5MHz Z80A and equipped with a 40-character, eight-line monochrome LCD of the type seen on the Tandy 100 and other handhelds of the time. Like Epson’s pioneering HX-20, the Sord portable had a built-in microcassette recorder for program and data storage.

Sord advertises the M5 Pro and M5 Jr - aka the M5 Turbo and M2 - in Japan. They never made it to the UK

In 1985, Sord later upgraded the IS-11 with a larger display, in the process converting the machine into a clamshell format and naming it the IS-11C. By then the company had come to the attention of Toshiba, which was eager to establish itself as a major manufacturer of portable personal computers. Toshiba acquired Sord that year, eventually turning Shiina’s firm into its Personal Computer System Corporation division, though it was undoubtedly working closely with it beforehand.

Shiina was adamant in his 1994 interview that it wasn’t Toshiba that was behind the 1983 smear campaign. It’s said that the deal with Toshiba was struck to prevent Sord’s collapse into bankruptcy, a result of failing confidence in Sord, a result of the rumourmongering. Shiina stayed with the firm for two more years, then quit to establish Asian PC maker Proside in 1987.

By then, in the UK, the M5 was a distant memory, or a box some folk pulled out of the cupboard during moments of nostalgia. It’s not known how long CGL continued to offer its own-brand M5. During 1983 it never rose higher than 15th place in the chart of best-selling micros under £1000 - lower even than the likes of the Mattel Aquarius, the Tandy Color Computer and the Colour Genie, and a peak reached in late October/early November. A year later, it was still on sale, but CGL has been forced to drop the price to below £50 to shift it.

You know the story: too little third-party software and so too few buyers to encourage further independent software development. ®