This article is more than 1 year old

CSIRO scales up solar cell printing

Five yards of electricity, please

One of the big problems in the world of printed solar cells is scale: it's much easier to print a cell the size of a fingernail than one of useful size. Australia's Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) believes a process announced last week changes all that.

Doing the hard work is a $AUD200,000 printer that CSIRO is operating on behalf of the VICOSC (Victorian Organic Solar Cell Consortium) of which it's a member, along with the University of Melbourne, Monash University and industry.

Instead of fingernail-sized cells, the new machine produces solar cells 30 cm wide – a key step in making ink-printed solar cells compete on price with conventional technologies.

CSIRO's Dr Scott Watkins told The Register that to get the large-sized cells, the consortium focussed on developing materials that could be dissolved and coated onto a substrate. An organic compound called P3HT – a polythiophene – as the positive charge carrier, and a fullerene called PCBM as the negative charge carrier.

“We're working on developing new polymers to replace each of these, to capture more light and deliver higher voltages,” Watkins said.

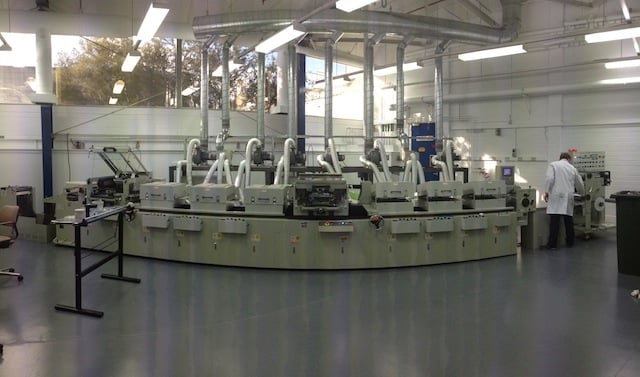

The large-scale solar cell printer. Source: CSIRO

Because these organic semiconducting polymers are very thin, they capture a large amount of light relative to the surface area.

At small scale, these polymers can easily be printed using spin coating – the dissolved polymer is deposited onto a spinning surface. This doesn't scale up, however, and wastes a lot of the material you want to use. The processes CSIRO developed focussed on developing the right ink, choosing the right type of rollers, and controlling the speed of the rollers to deposit the ink on the target material.

The result is a combination of screen printing, slot-dye coating and reverse-gravure printing. “The combination of those give us he best coating of the different materials.” Commercial partner Innovia, which produces printed plastic banknotes, was a significant contributor to developing the technology, he added.

As well as improving the materials, Dr Watkins told The Register that the group will also work on ways to order the positive and negative charge carriers to improve energy extraction.

“We don't have a lot of control over ordering – the positive and negative carrying materials are deposited very randomly.”

The only reason the process works at all, he said, is because the material is so thin, which means that charges don't have to travel very far – in-film distances are in the order of 10 to 50 nanometres, he said.

“There will be places where charges are blocked or lost,” he said – reducing those with more regular ordering will improve performance, and a long-term development goal is to create self-ordering materials.

The process currently delivers between 10 and 50 Watts per square metre, with lab-scale devices tested at as much as 80 Watts per square metre. When they scale up their materials purchases, the researchers believe they can achieve costs of $1 per Watt. ®