This article is more than 1 year old

Inside Intel's Haswell: What do 1.4 BEELLION transistors get you?

The brains and the brawn of the next Windows 8 slabs

Feature Intel’s Haswell processor architecture - formally called the fourth-generation Intel Core architecture, which is what the chip giant prefers we call it - has been in development for at least five years. Here's everything you need to know right now.

It first appeared on the company’s product roadmap in the summer of 2008 merely as a codename and a process size, 22nm, but you can bet early work began before that time.

In 2008, Haswell chips were scheduled to ship in the second half of 2012. Chip design is never straightforward, of course, and engineers need time to build on lessons learned when previous generations get a commercial release and are truly market-tested. So it has taken Intel’s engineers a little longer to get Haswell out of the door than they first thought would be the case, though, to be fair, by 2011 Intel was saying Haswell wouldn’t arrive until 2013.

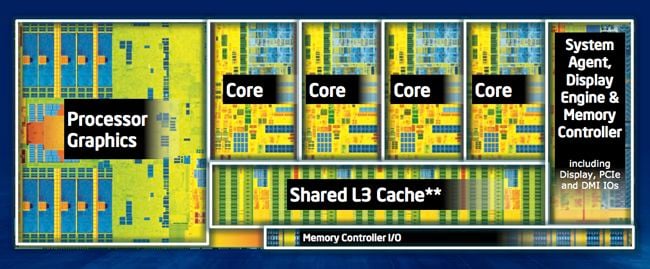

Inside the quad-core Haswell

And here, less than a month before the forecast first half of the year launch window is up, is Haswell. Intel unveiled mainstream and performance-enhanced mobile-aimed quad-core processors on its Core i5 and i7 lines, all with the customary accompanying IO chip, though more of its system logic than ever before now resides on the processor die itself.

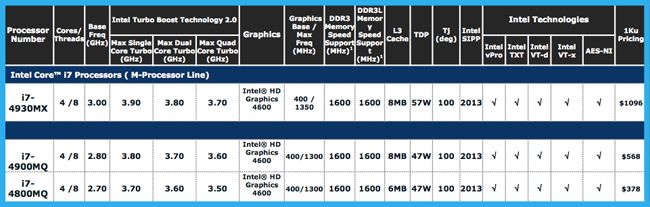

Intel says it will have about 19 Haswell-based mainstream mobile processors out during the remainder of 2013, but it’s kicking off with five of them, all branded Core i7, and all four-core, eight-thread parts.

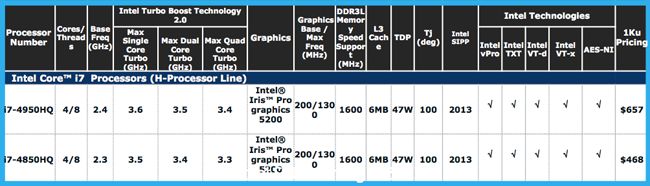

Lining them up in model number order, we have the 4800MQ, the 4850HQ, the 4900MQ, the 4930MX and the 4950HQ. The HQ’s have slower cores - 2.3GHz and 2.4GHz - but faster graphics, hence higher model numbers than the higher-clocked MQs sport. TurboBoost technology allows one or more cores to be clocked higher if that’s achievable within the chip’s thermal envelope.

The HQ chips come with Intel’s Iris Pro 5200 integrated graphics core, the MQs with the HD Graphic 4600 GPU. Different branding, yes, but the same basic core design, Intel engineers say, just with more execution units in the higher-numbered core.

Speeds and feeds

The MX has the 4600 GPU too, but its dynamic clocking can go a little higher than it can in the others. Like the 4900MQ, the 4930MX has 8MB of shared L3 cache - all the other debut mobile Haswells have 6MB - and it has a TDP of 57W. The others consume up to 47W. Prices run from $378 to $1096.

It’s broadly the same story with the quad-core CPUs that make up Intel’s debut desktop Haswell line-up. TDPs range from 35W to 84W among the i7s, with base clock speeds running from 2.0GHz to 3.5GHz, again able to go higher using TurboBoost. Most have HD 4600 graphics, but one, the 4770R, uses the Iris Pro 5200, though it only has 6MB of L3. All the others have 8MB.

Running up line, we have the the 4765T, 4770T, the 4770S, the 4770, the 4770K and the 4770R. The K is unlocked - the R, S and T suffixes relate to... well, who can say? Intel uses the codes to indicate TDP and thus the form-factors these might be best slotted into: T is 45W; even though they come sooner in the alpahbet, S and R are both 65W, but R has better graphics; and K is 84W. Ditto the suffix-less 4770, so the K actually indicates the chip is unlocked, not its TDP. Clearly though, the higher the letter, the lower the TDP.

Debut mobile Haswells: M series (top) and H-class CPUs

The R’s price has yet to be revealed but the top-performing K costs $339 and all the others are priced at $303 which really does indicate the suffixes are more about indicating form-factor suitability than anything else.

All the quad-core Haswell Core i5s have 6MB of L3 and all include the 4600 GPU. They run from 2.3GHz to 3.4GHz, each going higher still, if possible, using TurboBoost. But none of them support HyperThreading. They’re all 4670s too, again separated by an T (45W), S (65W), K or no suffix (84W).

The desktop chips are, perhaps, something of a sideshow - a box to tick. Intel is far more interested in the mobile side of the story, not surprisingly given the fact that notebooks now outsell desktops by a fair margin and may well do so to an even greater degree if the Haswell’s architectural benefits deliver the battery life boost Intel claims they will. Reducing power draw benefits desktop computers too - or, rather, the folk who pay for the electricity that powers them - but it’s not as important to desktop users as increasing battery life is to laptop owners.