This article is more than 1 year old

The toy of tech: The Mattel Aquarius 30 years on

'A machine so cheesy, they should have supplied rubber gloves to wear while using it.'

Game on

ECS was formally launched in January 1983 at the winter Consumer Electronics Show (CES) in Las Vegas, but it came too late for Intellivision. By then the console market was already being superseded by home microcomputers. In the US, Commodore was selling hundreds of thousands of Vic-20s - some 800,000 in 1982 alone - and had begun shipping (slowly) the 64 that summer. Atari’s own 400 and 800 micros were doing well too, as was Tandy’s Color Computer, and Texas Instruments’ TI-99/4 and TI-99/4A. The Intellivision, even with the ECS alongside it and a library of 100-odd games cartridges, was going to struggle to compete. Worse, it was now being out-performed by a newer home games entrant, the Colecovision, which arrived during 1982.

At CES, Mattel showed select retailers the Intellivision III, a much more sophisticated device with six sound channels, built-in voice synthesis, “nearly infinitely programmable colours“, 320 x 192 pixel graphics and “remote battery-operated hand controllers”, all rushed in to beat the Colecovision. But the III never made it past the prototype stage even though Mattel announced publicly that this “revolutionary video game system” would ship later in 1983. A more compact, cost-reduced version of the original, called the Intellivision II, arrived instead.

But Mattel decided it still needed a new, more up-to-date machine to sell to punters more eager to buy a computer than a console. It’s not clear whether it considered developing a true home computer in-house, though its experience with the Keyboard Component may have dissuaded it from doing so. Ditto the time it might take its engineers to design and produce a computer from scratch. Mattel executives now knew that a short time to market was essential.

What is certain is that Mattel approached third-party hardware companies in search of a machine that could be created quickly, which didn’t need to be compatible with the Intellivision and could be released under the Mattel brand. Among them was Hong Kong-based Radofin Electronics, which happened to have a couple of machines in the pipeline nearly ready to go and conveniently was a firm Mattel already knew well: Radofin manufactured some of the Intellivision units Mattel was still pumping out.

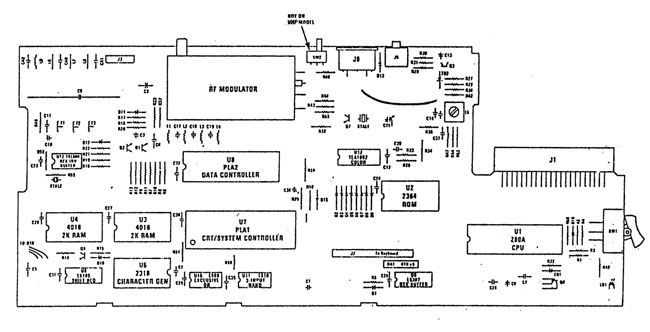

Codenamed Checkers, the new Mattel home computer would eventually be announced, in early 1983, as the Aquarius. Radofin’s machine, like most early 1980s home computers from Asia, was build from off-the-shelf components, in particular the well-established Zilog Z80A processor - in the Aquarius clocked at 3.5MHz and made under licence by NEC - and Microsoft Color BASIC. It would ship in the US in June 1983, and arrive in the UK the following September, Mattel said.

The home computer

The Aquarius was specced up with 8KB of ROM, a 48-key rubber calculator-style keyboard, video output via a TV modulator, plus printer and cassette ports - Mattel would offer suitably branded devices to plug into these. The machine was able to take ROM cartridges. The power brick was built into the casing. The machine would ship with a clip-on keyboard overlay for folk who preferred to enter BASIC keywords with single-key presses rather than typing them in.

Yet it was behind the curve in many respects. “The standard computer contains 4KB of memory,” wrote Chris Palmer in Personal Computing Today, “but after the operating system has taken memory for its own workings and for the screen and colour memory, you are left with 1731 bytes for your own programs.”

There was no way to program graphics, a shortcoming Mattel engineers sought to overcome by imposing a new character set on Radofin, this one with a host of glyphs from which more complex and games-friendly graphics could be formed. Running people, aircraft, stars, aliens and explosions were added.

It’s said that Mattel Designer Bob Del Principe, scoffing at the Aquarius’ poor graphics capabilities, suggested the following slogan for the new computer: “Aquarius - the system for the Seventies.”

The Aquarius could display 16 colours on its 40 x 24-character text screen, but it was officially capable of only 80 x 72 pixel graphics, and it had a single audio channel. A promised "expander" unit would up that to three channels, provide an extra slot for a memory cartridge of up to 16KB in size, and add a pair of ports for the two Intellivision-style games controllers that would be bundled with it. Since the expander was designed to clip into the Aquarius’ own cartridge slot, it would also incorporate a second such slot for game ROMs rather than memory. Both slots were protected with spring-loaded doors.

“Other peripherals will follow in 1984 - floppy disc drive, modem and a Master Expansion Module giving Extended Microsoft Basic,” wrote Popular Computing Weekly at the time. The Master Module - or Maxi-Expander, as it became known later - would allow the Aquarius’ RAM to rise to 52KB.