This article is more than 1 year old

KEEP CALM and Carry On: PRISM itself is not a big deal

But yes, Skype's no longer safe ... and keep an eye on GCHQ

Content usually isn't king, when you're a spook

Most of these requests were for what Microsoft calls “noncontent data”, such as account holders’ names and addresses, gender, e-mail addresses, IP addresses used, and dates and times of message or data transmissions, while 2 per cent of the requests were for the contents of e-mails or of files stored on SkyDrive.

Where did the guys who did the Olympics 2012 logo go next?

Skype, owned by Microsoft, has admitted disclosing administrative details of 4,713 Skype accounts during 2012, including Skype user IDs, supplied names, e-mail address and billing information, as well as call detail records if a person subscribes to Skype In or Skype Out services that connect to the normal telephone network.

According to the New York Times, Microsoft released no content from Skype transmissions during 2012, allegedly because “the peer-to-peer nature of Skype’s Internet conversations means the company does not store and has no access to past conversations.”

This and more recent and carefully worded statements from Microsoft fail to deny that if a Skype ID is targeted for interception, VOIP call content can then be copied to an interception centre and recorded.

But Microsoft’s statement is irrelevant because precisely the same situation applies as for normal telephony; there is no automatic recording of calls, so past conversations that were not intercepted at the time can never be accessed. But once an electronic tap is in place, everything can be rerouted, monitored and stored by the requesting agency. Many privacy activists suspect that when Microsoft re-engineered Skype supernodes to be exclusively under company control in 2012, the interception gateways were opened up.

Google’s 2012 transparency report says that it received and processed 47,479 US law enforcement requests for information – about double the total number of NSA PRISM reports produced in the same year.

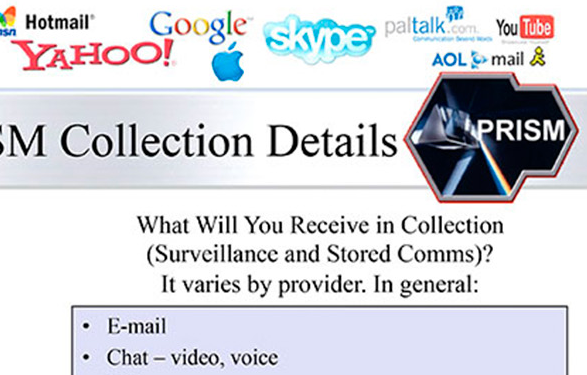

All nine US companies are reported to have stated they had never heard of PRISM before The Guardian report came out. From material published to date, there is no reason to disbelieve this, as PRISM appears to be no more than the internal, secret NSA name for intelligence sources that provide an internal web page to authorised analysts, from which users can choose from a shopping list of which company to go to and what each company has agreed to supply. Why should the companies have known the secret internal name?

What all of them have done, and some like Google and Microsoft been moderately open about describing in disclosure statements and pages, is to set up offices and rooms and systems which service authorised law enforcement (including intelligence agency) requests, and have them extracted from their record base by bespoke systems.

This is very different from wholesale access, downloading, and general trawling and data mining. The Guardian scoop the day before PRISM revealed a secret warrant directed to communications provider Verizon requiring wholesale delivery of all call data records from their entire system. That, and doubtless a flood of identical orders to other communications companies, is unambiguous data mining and warrantless surveillance.

PRISM thus also appears little different from what goes on in over a hundred SPOC (Single Point of Contact) offices in UK police and other agencies, where specially trained officers receive signed authorities under the 2000 Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (RIPA) to go collect communications data. All major UK telcos now provide secure web interfaces through which SPOCs can give their IDs and passwords, insert the authorised requests and then receive web or e-mail downloads of the requested data.

In contrast to the US, no UK CSP or telco publishes figures as to the number or type of law enforcement or intelligence agency requests they receive. They are not permitted to reject requests, US companies can inspect the requests and say no – and tell the public how much is asked, and how much rejected.

PRISM appears only to differ from what is now in place for both US and UK telcos in that it accesses web based services. Britain has no equivalent companies, as they are all US based, so and requests would have to be routed there.

The Guardian has quoted a figure of 187 requests processed by NSA for GCHQ during 2012. This too is a small number. GCHQ’s requests could easily be compliant with British law, provided that normal RIPA requests were made, and then passed to GCHQ analysts with online access to NSA’s PRISM page.

Significantly, when GCHQ recently gave evidence to the Intelligence and Security Committee in support of the Communications Data Bill, they may have forgotten to mention that they already had access to Hotmail and Gmail and many of the other services which they said were “black holes” requiring new systems and powers. We do not know for sure, as some of their evidence was redacted. It will have to be checked again by those in the know.

Ironically, the PRISM disclosure may, when more carefully considered, buttress the continuing British campaign against the re-introduction of the CDB – not because PRISM surveillance was unlawful, but because, being lawful, it shows that GCHQ and the Home Office were having Parliament on when they demanded new powers and systems for Internet intrusion.

The picture of PRISM that emerges from this analysis leaves me uncomfortably comfortable with the claims made by Barack Obama and William Hague alike: that PRISM complies with applicable law, and may be stature or warrant based - and need not be disproportionate, despite the alarm engendered by NSA’s boasting.

The opposite is the case with the wholesale copying of call data records from Verizon and, in all probability, from other US carriers. Whether the same happens between GCHQ and O2, EE, Vodafone, BT and Three is not known.

The bottom line on PRISM in particular may be that NSA doesn’t just bug us big time, all the time. They also do braggadocio, big time. ®

Duncan Campbell trained in physics and has worked as an investigative journalist and television reporter and producer since 1975, specializing in investigating sensitive political topics, including defense, policing, intelligence services and electronic surveillance. His scoops include revealing many aspects of international espionage, including telephone tapping and the Echelon satellite interception network.