This article is more than 1 year old

Love in an elevator.... testing mast: The National Lift Tower

El Reg shows where you can go and get truly shafted

Geek's Guide to Britain The Tower rises above the flat plain of the Nene valley near Northampton - for centuries home of Britain’s shoe industry, but these days better known as the home town of 11th Doctor Matt Smith, comics auteur Alan Moore and El Reg operations manager Matt Proud - like some kind of latter-day Barad Dûr or Orthanc.

The sinister cylinder, reaching 128 metres up from the ground, isn’t cut from black stone, but formed from concrete as grey as the Midlands sky. Its smooth surface is punctuated only by a series of viewports, black against the smokey wall - they hardly warrant the word "window", with its connotations of illumination. The peak is terminated with a series of jutting steps and gaping maws like some massive crenelation from which a Dark Lord might gaze forth across his domain.

Concrete and steel

In fact, this monument to 1970s design and 1980s construction was built for far more mundane purposes. Now called the National Lift Tower, it was originally raised by the Express Lift Company for testing elevators prior to installation, and for training the engineers who would tackle the lifts’ maintenance.

Express had been manufacturing lifts in Northampton since 1909 when one of its founding firms, Smith Major & Stevens, moved out of London and established the Abbey Works, so called because it was constructed on the site of a Medieval monastery. Construction work on the factory was frequently interrupted by the unplanned exhumation of many a cenobite’s skeletal remains.

Like the monks of the Augustinian Abbey of St James, Express has long since shuffled off its mortal coil. Its original owner having gone to the great winching room in the sky in the mid 1990s, the NLT is now no longer used for testing elevator rigs before they go into buildings, but rather for R&D across industry and academe. These days it’s as likely to welcome a group of weekend abseilers as a team of elevator maintenance trainees.

Shaft!

Located just a conversion kick from Northampton Rugby Football Club’s Franklin’s Gardens ground - go, Saints! - the Tower’s facilities include six lift shafts of varying heights and speeds, one of which is a high-speed tube with a travel of 100 metres and a theoretical maximum speed of ten metres per second. The Tower also has a drop-test facility with a height of 30 metres and a lifting capacity of 10 tonnes. The building also encompasses what the current operators sinisterly describe as a “void used for research” - it’s 77 metres deep.

I peered through the foot-diameter hole used to send smaller objects on their way down, and it’s not a view for those with a fear of heights. The tower isn’t generally open to the public, but I was kindly shown around by Ed Wright, one of the three-man team that now runs the NLT. In a former life, Ed was a server wrangler, and one of his many tasks as the Tower’s administrator and factotum is implementing the facility’s IT network and AV set-up.

When the NLT partnership took over the Tower five years ago, there were almost no facilities remaining within the concrete shell. The building wasn’t derelict, but in the years since Express Elevators’ collapse, the firm’s subsequent acquisition by US lift colossus Otis and the eventual sale of the land on which the Abbey Works had been established, the Tower saw little use.

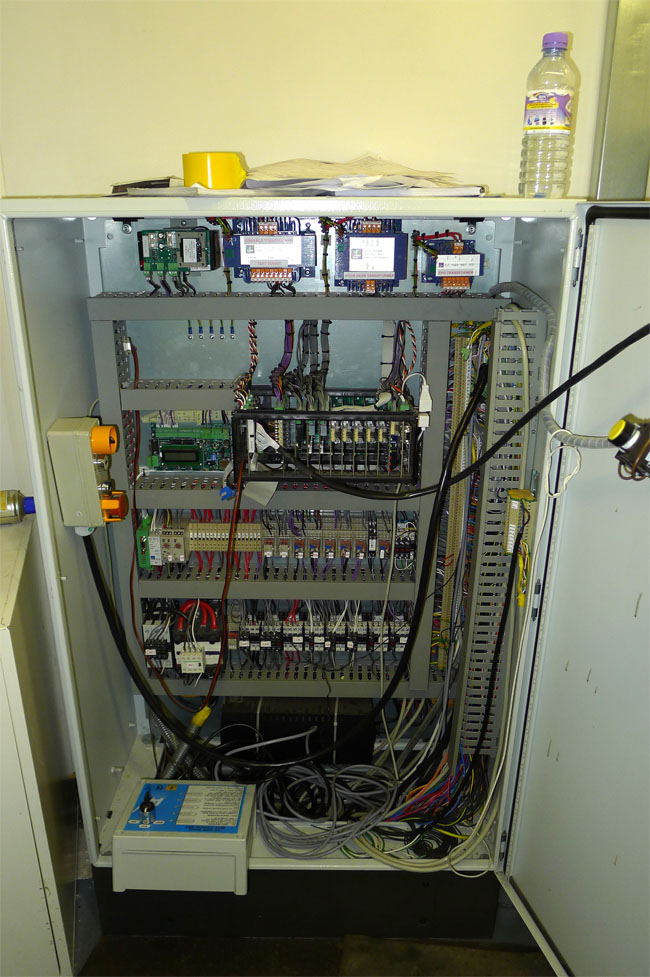

Winch control de nos jours: to upgrade your motor, just download a firmware update

Not so now. Ed and partners Pete Sullivan - the building’s owner - and Matthew Fenn had the Tower reconnected to the grid and other key utilities, fitted out workshops and training rooms, and began to pitch the building to the elevator world as a unique research and development facility in the UK. The NLT is currently being rigged with the latest in winching systems - one of which will allow ascent speeds of 17 metres per second or more, using a gearless magnetic mechanism and microprocessor control - and the buffers used to arrest carriages descending at such high speeds. It’s getting a hi-tech hydraulic lift system too.

And it’s not just the lift industry that has expressed an interest in the old Express tower, says Ed. Boffins and engineering companies from across Europe now use the Tower to test and evaluate safety systems for technicians working at great heights - and miners working at great depths, since the Tower’s voids can simulate shafts descending into the Earth’s crust just as well as they can the side of a mast supporting a power-generation turbine.

If it’s dangled or dropped from a great height, or has to move up and down the space in between, the Tower has room to test it.

And its cheaper, says Ed, briefly donning his sales hat, than specially rigging up a tower crane to do it.

The gaps at the top prevent the Tower swaying in high winds

This is today - back in the mid 1930s, elevator people had to make do with Express Lifts’ first tower, an 18-metre job rising up through the roof of the Abbey Works plant. This erection satisfied Express engineers’ needs for the following 40 years, but in the late 1970s it was decided they had to have something rather larger - a building tall enough, in point of fact, to give high-speed lifts the space not only to accelerate up to speed but to run for a suitable distance and then decelerate and come safely to a stop.