This article is more than 1 year old

Love in an elevator.... testing mast: The National Lift Tower

El Reg shows where you can go and get truly shafted

Column inches

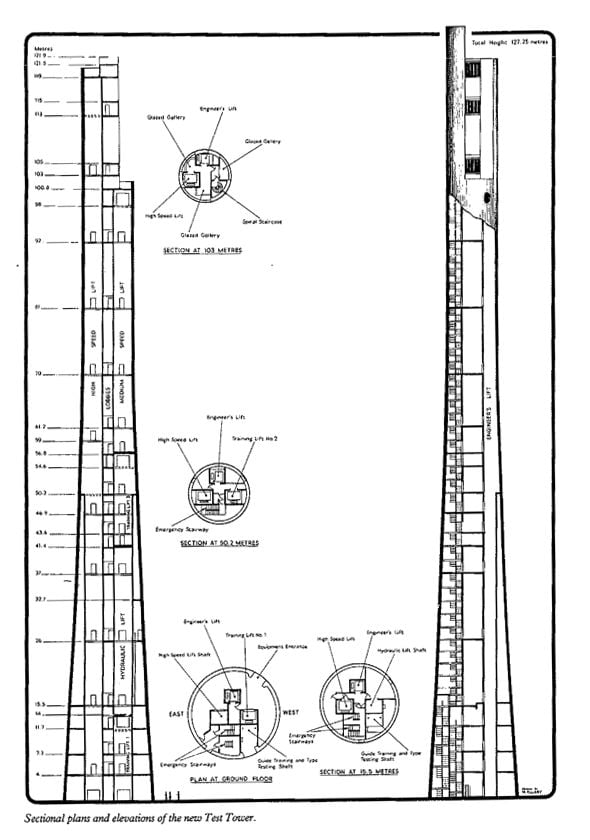

Planned with an operational life of 25-40 years, the new tower would contain not only test shafts each running at various speeds, but service lifts and training rigs for maintenance crews and rescue personnel. Should the power be lost, workers could ascend and descend the Tower using a staircase running up the full, 20-storey height of the building, lit by daylight, and zigg-zagging its way up through the structure.

Source: Express Lift Company/The National Lift Tower

The Tower’s design, by architects Stimpson and Walton of Northampton, was finalised in 1980 and work began shortly afterward, with London-based Tileman and Co handling the construction work. Raising the tower took just over two weeks, with concrete being poured into a series of moulds which would rise up on the dry concrete below as the tower’s height increased. The peak rate of growth: 300mm an hour, or 7.2 metres a day.

Pausing only to curse Windows 8’s Modern UI - once an IT pro, always an IT pro - Ed shows me the company’s collection of photos taken during the Tower’s construction.

The Tower was built on a 24-metre wide, three-metre thick concrete "raft", set down in two separate pourings. The raft allows the 4,000-tonne Tower to float on the soggy soil prevalent in these parts. Ed describes the set-up as a “pencil balancing on an aspirin”. From the raft, the tower tapers through roughly half of its height before rising as a cylinder from then on, its diameter shrinking from 14.6 metres at the base to 8.5 metres. The tapering helps the Tower withstand the buffeting of the wind.

Britain’s lift capital, once

The Tower’s unusual peak helps too, acting to dampen lateral movement in high winds. The trick was to leave the concrete outer cover off the upper section, exposing the lift shafts and walkways to “reduce the suction force on the leeward side by virtue of the through-holes and irregular shape breaking up the vortex effect”, as Express Lifts’ own description of the facility puts it.

Above and below are glass-sealed decks, but the top level is open to the elements. It provides a splendid view of Northamptonshire and surrounding counties, but most of the folk who go up there these days immediately go sliding down the outer skin on ropes after climbing out over a gantry that originally held a BT point-to-point microwave transceiver. A second dish, aiming south, is still there, but unused.

On completion, the Tower was “one of the tallest lift testing towers in the world” and one of only two of its kind in Europe, was formally opened by the Queen on 12 November 1982.

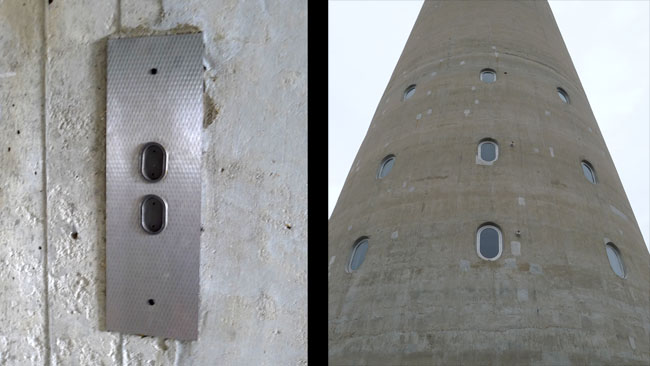

Lozenge lounge: the Tower’s windows were designed to match Express’ lift controls

Express Lifts itself was formed in 1928 through the merger of Smith Major & Stevens (SMS), GEC Elevators and Easton Lifts, though the firm could trace its history back to the 1770s thanks to SMS’ long history as a maker of hoisting gear.

In the early 1990s, Express merged again, this time with fellow UK lift company Evans, but the partnership was not successful and the combined company soon went bust. It was acquired by US elevator giant Otis, which still uses the Express & Evans brand in some installations.

Otis may have been keen to keep the brand, but it wasn’t interested in the Tower. The American company quickly sought to capitalise upon its acquisition by selling off the land on which the Abbey Works was situated. The area was soon in the hands of property developers, who wanted to pull the Tower down. The building’s safety was called into question, and scare stories appeared in which it was claimed it was suffering from “concrete cancer”.

Local protest saved the Tower from demolition, even though Express’ Abbey Works was razed to the ground to make way for the housing estate in which the Tower sits more or less in the centre. Clearing the factory site at least finally allowed, in 1999, for a proper excavation of the Abbey by Northamptonshire Archaeology.

Mind your step

The Tower is now a Grade II listed building. As for the “concrete cancer”, it’s true, there were some parts of the building with a high level of ironstone in the mix, leading to rust staining on the exterior, but Ed and his colleagues were able to have them cut out and refilled, so that key modern building regulations could be met.

There’s no reason, then, that the National Lift Tower - not merely a monument to Britain’s modern industrial heritage but also, pleasingly, a working building once more - won’t gaze out across the Nene valley for many, many years to come. It can now continue to do its bit for the British light industry renaissance, at once defining Northampton’s skyline and giving the thousands who pass by on the M1 motorway something to ponder: “What the bloody heck is that for?” ®

GPS

52.238627, -0.922070

Post code

NN5 5FH

Source: Google

Getting there

From Junction 15A of the M1, take the A5123 North and then the A5076. Turn right onto the Weedon Road (A4500) toward Northampton Town Centre. Turn right onto The Approach, which runs right up to Tower Square.

Northampton can be reached by train from London Euston or Birmingham New Street.

Entry

The Tower is not generally open to the public, but the exterior is readily accessible for exterior photography.