This article is more than 1 year old

UK micro pioneer Chris Shelton: The mind behind the Nascom 1

...and Clive Sinclair's PgC Intel-beating wonder chip

Designing the Nascom 1

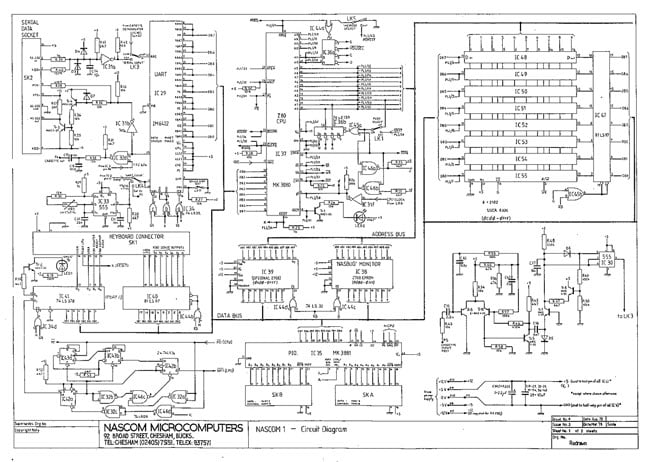

The Nascom 1 design process was straightforward, Shelton says. The only trouble arose from Marshall’s choice of PCB layout contractor. The task of converting Shelton’s schematics into a circuit board layout was handled by an Irish firm selected because it could do the job using an early Computer Aided Design (CAD) system, which Marshall insisted upon. Unfortunately, the process was time consuming and costly. When the design came through and was found to be unnecessarily large, it was too expensive to change.

The result, says Shelton, is that the Nascom’s board was much larger than it needed to be. “It could have been a lot smaller,” he recalls.

Shelton’s design work was outlined in a series of articles published in 1977 and 1978 by Wireless World magazine, though today he doesn’t remember writing the articles that went out under his byline. The series had presumably been pitched by Marshall or Borland having seen how successful a similar article in the January 1975 issue of Popular Electronics had been in pushing the MITS Altair 8800 kit computer to forefront of the US micro enthusiast scene.

Marshall and Borland also devised a series of events called the Home Microcomputer Seminar, the first of which was held in the Wembley Conference Centre on 26 November, 1977. The prototype Nascom 1 now complete, Chris Shelton was on hand to give the new British micro its public demo.

The unveiling was an unequivocal success. The seminar attracted about 500 paying visitors - tickets cost £3.50; more if you wanted lunch included - and many of them immediately placed orders for the new machine. Kerr Borland claimed early in 1978 that some 400 had been ordered in the two weeks after the seminar and some 2,000 enquiries for more information had been received. Individuals placed orders, and “20 or so colleges have ordered one or more computers”, Borland wrote.

Shelton says John Marshall’s sales forecast predicted that roughly a thousand units would ship in the first year, “but sales were an order of magnitude greater than that”. Demand for the Nascom 1 was massive, and both Nasco and the subsidiary Marshall set up to make and sell the computer, Nascom, were entirely unprepared for it. With a clear success on his hands, Marshall raced to hire technical, sales and support staff - more, Shelton reckons, than was entirely necessary. The expansion certainly increased Nascom’s costs, making cash flow precarious and hindering the company’s ability to ramp up production to meet demand.

Britain’s most popular micro

The Nascom 1 was offered as both a self-assemble kit and as a fully built system that was slightly more expensive. The cost of bundling a high-quality Qwerty keyboard had already nudged the base price past £200 to £239.76 including eight per cent VAT; it only came in under £200 if you bought it without a power supply. The kit version - “a board and a load of chips in a bag” is how Shelton describes it - caused no end of tech support calls. Shelton says he got a look at the units that had been returned and almost none could be salvaged and re-used, such were their users’ poor soldering and assembly skills.

By the summer of 1978, Nascom staff were claiming the Nascom 1 had become the UK’s fastest selling microcomputer, with orders by then approaching £2m in total. That’s fewer than 10,000 units at just over £200 a pop, but still much more than the 300 to 400 Marshall had anticipated would be sold. Three quarters of the Nascom orders were coming in from the rest of Europe. As Your Computer noted a few years later, the Nascom 1 and Nascom 2 were “at the end of 1979, the most popular range of single-board computers” - more popular than Science of Cambridge’s MK-14, more popular than Acorn’s System 1 microcomputer. And £200 was considerably less than the prices the first few Apple IIs, Commodore Pets and Tandy TRS-80s only now starting to appear in the UK were commanding.

Shelton’s association with the Nascom 1 now largely came to an end. He briefly travelled to Munich to help a former colleague of John Marshall launch the Nascom 1 in Germany, but that was it. Shelton Instruments had other projects on the go, and he returned to London to oversee them as he had before. Among them: selling a series of graphics cards for a then little-known Canadian hardware company called Matrox.

Nascom itself created the Nasbus peripheral connectivity systems later in 1978 and, the following year, introduced the Nascom 2, a Nascom 1 with a higher clock speed, more RAM and ROM capacity, and a higher price at a time when other micros were getting cheaper. “The Nascom 2 makes extensive use of ROMs for on-board control decoding. This reduces the chip count and allows easy changes for specialised industrial use of the board,” said the firm’s ads. “We think no other board has quite so much in it for £295 plus eight per cent VAT. If you find us a board that has more, buy one for us too!”

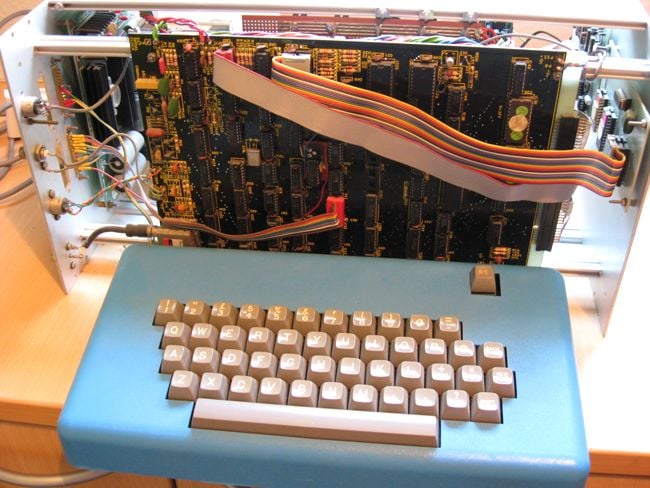

The most popular board micro - still working

Source: Howard Smith

While Nascom was struggling to cope with high demand and, from 1980 onwards, declining sales - it would eventually be acquired by car part maker Lucas’ technology division - Chris Shelton found himself working on a variety of projects designing, and in some cases producing, microprocessor-based industrial controllers. Among them, controllers for Gestetner copiers and printers, and for the broaching tools used in the construction of jet engines. This led him to work increasingly with Programmable Logic Controller (PLC) units, devices for which he holds a number of patents.

During the late 1970s, Shelton was joined by Neil Harrison, who had briefly worked for Nascom but by now was a co-director of Shelton Instruments. SI’s business had expanded, with half of the company’s turnover now coming from consultancy and the rest from manufacturing, much of it off the back of the consultancy work. Harrison now suggested that some PLCs could be replaced with modules based on a general-purpose CPU, such as the Z80.

PLCs emerged in the late 1960s as a replacement for the complex relay systems, timers and sequencers used in complex manufacturing machinery, particularly in the car industry, explains Shelton today. Early PLCs were programmed using “ladder logic”, so named because it replicated the sequential structure of relay logic diagrams. A bus replaced the connecting wires of the old relay linkages.