This article is more than 1 year old

Are you for reel? How the Compact Cassette struck a chord for millions

From fuss-free audio tape recording to Walkmans, it's all in your head

Getting duped

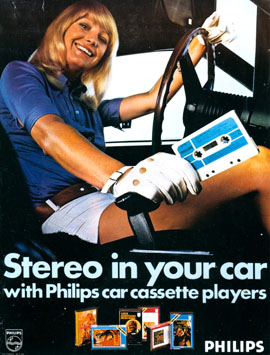

Philips in-car cassette player advertisement from 1971

Analogue cassettes in cars did a lot better than the

Digital Compact Cassette

Source: Philips Company Archives

There was a fair bit of ground to cover before the prevalence of Dolby on prerecorded cassettes became an issue. The winning combination of portable radio and compact cassette recorder emerged fairly early on when Philips produced its own model, the racily named Type 22RL962, in 1966. It followed this up in with a stereo model, the EL 3312, about a year later. In 1968 the RN582 car radio cassette made its debut. Other manufacturers were claiming firsts on various fronts as consumer audio products felt the benefit of transistorisation.

Music centres – all-in-one stereo systems with radio, turntable and cassette recorder – became commonplace in homes with audiophiles eschewing these in favour of hi-fi separates where the cassette ‘deck’ was manufactured with quality as the number-one aim, rather than affordability or portability.

With these various combinations gaining popularity through the mid-1970s and beyond, the issue of copying became a bone of contention. People were sharing their vinyl records and taping them. Records could be borrowed from public libraries and cassette copies made. It was stealing. In other territories, developing countries in particular, where the Compact Cassette was more widespread than other forms of recorded media, the sale of pirate copies was commonplace.

Friendly BPI campaign – not everyone agreed with its message

While these overseas activities were beyond the reach of Western record companies, back home in Blighty, the BPI led a campaign to bring our music-ripping nation to book in the 1980s. The slogan "Home Taping Is Killing Music" was the industry’s browbeating missive to counter its fears that record sales would suffer due as a consequence.

Yet for the consumer, taping and sharing music was a way of discovering new bands and for many artists, this was acceptable because it was a way of growing their fan base. Fans that would soon enough buy their records and probably attend concerts with their mates.

The pros and cons of copying is an argument that still rages to this day. Certainly, Philips had no idea that the introduction of a dictation machine some two decades earlier would lead to such strife.

There were other reasons for recording vinyl which many felt were perfectly legitimate. Why not have a recording of the album you bought to play in the car? What about those favourite tracks of yours? Mix tapes for parties, romance and just sheer pleasure were recordings young and old alike would painstakingly piece together from their music collections, manually taping each track. And it wasn’t just for use in the car.

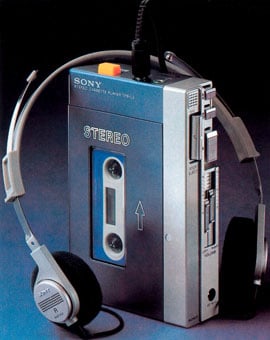

Sony's Walkman used headphones and made it all personal

The Sony Walkman was a game changer for the Compact Cassette, arriving in 1979, and sported headphones rather than a loudspeaker. Its portability triggered a craze for music on the move. A distinctive feature of Walkmans and its me-too rivals that followed was that they were playback only. Recording Walkmans were offered for more professional uses and became popular with reporters. Other brands would follow suit with some even including a radio in this portable package.

Twin cassette decks appeared too, enabling tape-to-tape copying and dubbing with some consumer models featuring a Walkman-style player that would dock in the main unit that contained the recorder. The genie was definitely out of the bottle as far as making copies of recordings was concerned.

It’s worth remembering that we’re well and truly in the analogue domain here and so tape copying would always bring with it the baggage of tape hiss. Unlike the world of digital audio that we are immersed in today, the signal would degrade markedly with repeated tape copying generations beyond the original source.

Even so, as the cassette recorder evolved, so did the media with chromium dioxide and eventually Type IV (metal) tapes offering improved dynamic range and frequency response. These new formulations required different bias frequencies which led to additions to the Compact Cassette standard. Hence, switches for ferric, chromium dioxide and metal that would adorn many Compact Cassette machines would all conform to their respective equalisation settings.

Going digital

Other improvements appeared such as Dolby C noise reduction along with HX Pro, the latter tweaked the bias for a "headroom extension" (increasing the dynamic range) but neither really took off. However, the enhancements in recording media and signal processing, together with the arrival of the Compact Disc, did mean that home recording was sounding better than ever. Another way of looking at it, though, was that this pristine digital disc format revealed the shortcomings in using cassette tape, particularly in its high-frequency range.

As vinyl took a backseat and the crackle-free fidelity of the Compact Disc made its presence felt, it was inevitable that a consumer digital recording format would emerge. Recording studios had been blessed with a number of options for some time, none affordable for the mass market.

See, I told you it was big: Philips DCC 900 digital compact cassette deck

While Sony pondered on what would become the MiniDisc, Philips hit upon the idea of the Digital Compact Cassette (DCC). It would support a resolution up to 18 bits and sample rates of 32kHz, 44.1kHz and 48kHz. The killer feature would be backwards compatibility with your existing analogue cassette library. The technical aspects of DCC are discussed in more detail here.

DCC worked, but the massive DCC 900 machine that was debuted wasn’t the in-car digital tape system that the dealers had been promised. That would come later along with the portable DCC 170 ‘walkman’. DCC failed not because it was technically lacking – it allowed track naming and sounded superior to early Sony MiniDisc models – but because the idea of fast-forward and rewinding tape was now dated in the minds of its target market.

Digital Compact Cassette (DCC) with an analogue cassette beneath it

These people were used to the instant access convenience of CD and were looking for the same in a digital recorder. Sony’s MiniDisc delivered this and won the day as a consumer digital recording format. That is until Apple’s iPod and iTunes promoted the concept of rip, mix and burn.

Fast-forward, eject

Philips claims that about three billion Compact Cassettes were sold in the 25 years between 1963 and 1988. Beyond that period, other formats ate away at sales: in the US alone, sales of Musicassettes dropped from about 450 million in 1990 to just over quarter of a million in 2007, according to Billboard. Yes, you can still buy tapes and cassette recorders remain in production too, but the choice is fairly limited.

Many of us continue to encounter cassette recorders as the equipment endures in car stereos, decades-old boom boxes that never die, and fully functioning hi-fi separates that we haven't the heart to bin. Whether this equipment is ever used to play a cassette is another matter, but I confess to owning a DCC 900 (I couldn't afford a DAT) and fire it up from time to time for both analogue and digital playback. It’s still going strong.

I’ve had the pleasure of finding out what the best of breed in the today's cassette recorder market has to offer, having just reviewed Tascam’s CD-A750. It’s a beast designed for studio use featuring balanced analogue XLR connectivity. On this model, alongside the Compact Cassette deck, is another Philips technology with Lou Ottens' fingermarks on it, the Compact Disc.

Thank you Mr Ottens, and happy birthday, Compact Cassette. ®