This article is more than 1 year old

Finns, roamers, Nokia: So long, and thanks for all the phones

The rise and fall of the great Finnish phonemaker

Special Report Finns are in mourning this week after Nokia has sold its mobile phones unit to Microsoft: a decision that weirdly seems both inevitable and shocking at the same time.

But they should be proud, for Nokia had an incredible 15-year run at the top of an entirely new industry, making stalwarts like Motorola and neighbours Ericsson look clumsy and slow. It outlasted both, and gave the world Nordic design and simplicity and top-notch engineering: all influenced by Finland’s world-class education system.

The company also reflected Finland’s outward-looking nature, even if not everyone knew where Finland was. I recall signing a lease with a Californian in 1999 who told me how much he loved Japanese technology products: “Sony – but most of all Nokia,” he said.

The affection the Nokia brand retains owes much to creating simple usable technology products in the 1990s and well into the noughties.

The rise

Surely everyone now knows by now that Nokia began life as a cable and rubber boot manufacturer in the 19th century. Nokia Ab, Finnish Cable Works and Finnish Rubber Works made it official in 1967, merging into the Nokia Corporation. By the late '70s Nokia created the radio telephone company Mobira Oy as a joint venture with Finnish TV-making firm Salora in 1979.

But Nokia only really became a recognisable name in 1982 when Nokia introduced a hefty (nearly 10kg) car phone called the Mobira Senator one year after the first international cellular network, the Nordic Mobile Telephone (NMT) service was up and running in Finland.

Back then, Nokia resembled an obscure Korean chaebol. The company was owned by the banks, and many of its buyers were the state or state agencies. It decided to adopt a new, optimistic and quite fearless business strategy.

Nokia examined its products where it led the market and where it followed a market leader with a "me-too" offering, and decided it had too many of the latter and not enough of the former.

Yet it could change that, by capitalising on Finland’s human capital, its engineering and language resources. Nokia had only 907 staff (out of 23,000) working in R&D in 1983 when the sea change began. Nokia briefly became the market leader for analogue carphones in the late 1980s but the success threatened to be buried by the company’s other poorly performing units.

In the late '80s, the Finnish economy started to liberalise and sweeping changes were seen across the country's business landscape.

Between 1989 and 1993 the company was a mess: it sold TVs and PCs among many other products, as the results of acquisitions. When in January 1992 the new CEO Jorma Ollila took over, mobile phone revenue accounted for just 1.1bn Finnish Marka, out of £6bn FIM total sales – with “cables and machinery” accounting for 1.67bn FIM.

Olilla’s plan was to become the leader in mobile phones, and the Nokia board considered it so risky they put their caution on the record, and demanded Ollila produce a "Plan B": in his strategy, Nokia would have to get much smaller before it got bigger.

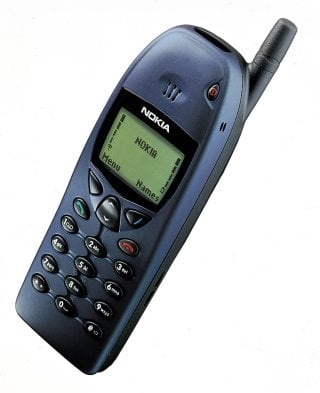

The Nokia 6110 from 1997. The first with icons and Snake.

Aimed at what Nokia called the 'Controllers' segment: business users

In fact, Ollila’s decision to "bet the company" on mobiles was spectacularly prescient. The airwaves were becoming deregulated, and it was no longer viable for one (or two) operators – one of which was state-owned – to enjoy the privilege.

More operators meant more customers for Nokia, and it also meant ordinary consumers could join the market. Which in turn meant manufacturers would have to market mobile phones in an entirely new way. Rather than taking the CIO out for lunch, they had to be easy to use, feel personal and even fun.

Ollila anticipated all of this. As the boss of the mobile division, he was confident that a single digital standard would also lower costs and drive adoption. In 1983, McKinsey had predicted that the global market for mobile phones would by the year 2000 be around 1 million subscribers.

The company soon become intricately involved with the development of cellphone networks.

It’s Nokia’s confidence, ambition and international outlook that really stand out in these years. By 1994 Nokia was publishing its board minutes in English. Meanwhile Motorola's annual company report that year finds a $22bn giant keen to talk about its two-way data pagers and the Iridium satellite network: "The first operational global wireless telecommunication network enabling subscribers to make or receive telephone calls over handheld subscriber equipment worldwide".(PDF)

By 1998 Nokia was shipping more mobile phones than anyone else.

As well as targeting simplicity, Nokia was doing things rivals didn’t dare contemplate: such as removable fascia for personalising the device. Nokia’s neighbour and swankier rival, LM Ericsson, also employed superb designers – but by the end of the 1990s had made a marketing virtue out of the distinctive stubby antennas on its mobiles. Nokia simply made the external antenna disappear, into the phone. Ericsson was the first of the three GSM giants to sell off its mobile phones division, in 2001.