This article is more than 1 year old

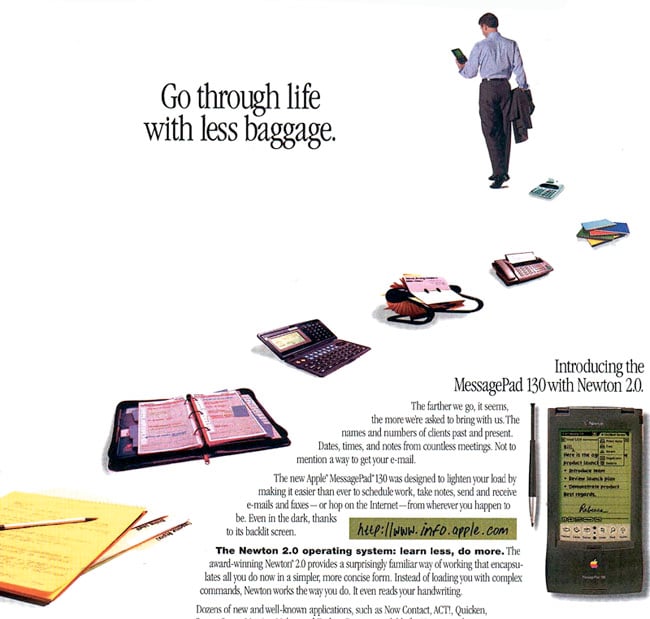

Stylus counsel: The rise and fall of the Apple Newton MessagePad

20 years on, the story of the handheld that might have changed the world

From pocket Mac to Pocket Newt

Sculley might have gone with Mercer’s machine had he not just given a keynote at the 1992 Consumer Electronics Show (CES) promising that Apple would ship a new category of device which he coined a “personal digital assistant” - the first use of a term that would become widely used through the 1990s and beyond.

It would be a gadget capable of allowing the user to communicate through email and handle all their personal information: diary appointments, to-do lists, their address books and such, all the while smartly spotting connections between them. Lunch with dad on the fifth? Sculley’s PDA would automatically load dad’s contact details so they were there if you needed to email or call and cancel. It would learn that you went swimming every Wednesday at 6pm and remind you accordingly.

The PDA business would be worth a then-staggering $3.5 trillion by 2003, Sculley predicted. Even today, that’s a colossal figure. Smartphone sales are in the billions, not trillions, even if you add app sales and service fees. Voice calling aside, what Sculley was predicting was indeed the smartphone market, had he but known it.

But it would take companies like IBM, Symbian, Nokia and Ericsson many years to create the first true smartphones. Even without the phone component, Newton just wasn’t going to come close to the vision Sculley outlined in his speech.

Still, the potential Sculley had outlined was enough to pique the curiosity of US telecoms giant AT&T. Its bosses could see, if Sculley and his engineers perhaps hadn’t, that a Newton-like device with access to the phone network – and by this point in time analogue mobile phones were widely available, and digital ones not very far off – could be big business in the years to come.

AT&T put out feelers, found Sculley receptive and, by early 1993, the two companies were meeting to discuss turning Apple into an AT&T subsidiary. They came close to an agreement, but AT&T’s earlier, unsuccessful acquisition of NCR and its already in play purchase of a mobile comms company, McCaw Cellular, gave AT&T bosses’ cold feet, and in April 1993, the Apple buyout talks were off.

And soon so was Sculley, forced to step down from the CEO job in June that year in part because of the delays getting Newton to market, though he stayed on as chairman until October when he resigned and left the company.

Back in 1990, as Larry Tesler was taking over the Newton project, that seemed a very unlikely outcome. And no one would have bet that a scheme set in motion by Tesler would eventually yield the world’s most widespread microprocessor platform, but that’s what happened.

Advancing ARM

Casting around for a chip that could sit inside a battery-powered handheld device and render a (for the time) high-resolution display without hammering the battery, Tesler got wind of Britain’s Acorn and its Acorn Risc Machine chip.

The ARM had been developed to power Acorn’s computers when the 6502 processor – which it had used in the Atom, BBC and Electron micros – ran out of steam. Acorn used the ARM in its desktop Archimedes computers, but its very low power draw while running and near zero power consumption when idling struck Tesler as just what the Newton needed. It was certainly better than the in-development AT&T part, codenamed "Hobbit", the Newton team had been considering thus far.

Conversely, Tesler’s Newton project must have seemed to Acorn co-founder Hermann Hauser as a dream come true: a realisation of an electronic book concept he’d been talking about since the late 1970s. Here was Apple building what was not so very far from the device he’d envisaged. Best of all, it could be powered by as Acorn chip.

The result was the creation, in November 1990, of an Acorn spin-off company, Advanced Risc Machines (ARM), part owned by Apple, part by Acorn’s majority shareholder Italian manufacturer Olivetti, and part by Hauser himself. Chipmaker VLSI had a stake too. Acorn handed over its ARM intellectual property.

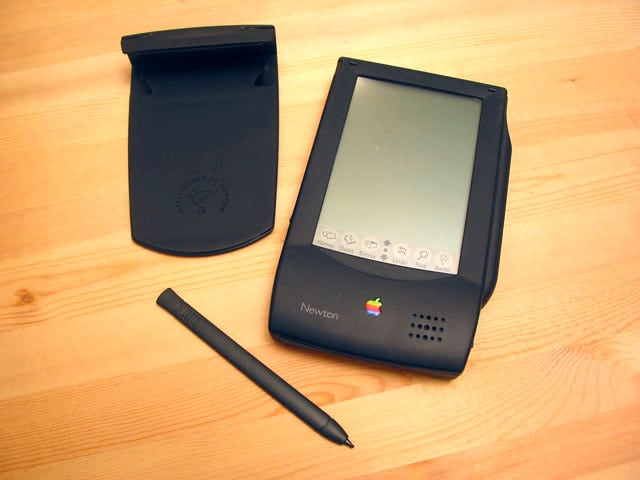

Junior cased, complete with dropped-before-launch screen cover

Source: Grant Hutchinson

Separated from Acorn, ARM would survive its parent’s collapse. Established with a plan to design and license processors for others to manufacture, ARM had the strategy that would encourage it to sign up partners who would put its chip architecture into, eventually, millions upon millions of mobile devices.

It’s fair to say that the Newton project made ARM the powerhouse it is today. Apple initially put in $2.5m in return for 43 per cent of ARM. In March 1998, it sold 18.9 per cent of a reduced stake and made $23.4m. Further sales would net it $792m in total, far more than the $100m John Sculley once said Apple had spent on the Newton project.

Apple had found a source of silicon: a 20MHz ARM 610 chip. The first product to use it would be Steve Capps’ Pocket Newt. In February 1991, Capps’ sponsor, Michael Tchao, had buttonholed Apple CEO Sculley on a flight to Tokyo. He made the case for canning Newton Plus - too big, too expensive, technically brilliant but just not sexy enough - and focusing the attention of the Newton team on the handheld. Sculley was persuaded: Pocket Newt would be the device Apple you take to market. But development of the slate would continue, to form the basis for a follow-up product. It became known as "Senior" to Pocket Newt’s "Junior".

So, in May 1992 at the Summer CES in Chicago, when the press got to see the Newton prototype for the first time, it was Junior they saw, not Senior. It wasn’t ready, of course. That summer, the Newton team became part of a new Apple division, Personal Interactive Electronics (PIE) under ex-Philips consumer electronics chief, Gaston Bastiaens. He was able to show a working Newton at the Winter 1993 CES, but wisely kept quiet about when the thing might actually be released. In fact, he had a new deadline: 29 July. To make it, that March he told the world he had frozen the Newton software. From now on the team would be tracking down and squashing bugs.