This article is more than 1 year old

CSIRO unveils new bushfire software and knowledge base

User feedback to help refine models

With Australia already embroiled in the earliest-starting fire season in memory, it's pertinent that the CSIRO is working on improving our ability to model and predict bushfire behaviour.

This week, the science agency presented a new tool at its Bushfire Behaviour Symposium in Canberra: Amicus, a decision support tool designed to give users access to both a knowledge base of fire behaviour, and 60 years' worth of cumulative refinement of fire behaviour modelling within CSIRO.

As Dr Andrew Sullivan (CSIRO's team leader in the Bushfire Dynamics and Applications Group) explained to Vulture South, fire is simply too complex a beast to fully model or predict inside any computer.

“Fire is a huge and chaotic chemical process”, he said, with parameters that extend “from the micron scale up to the tens of kilometres”. The best science can offer is to simplify this down into models that take a smaller number of inputs – fuel load, windspeed and topography, for example – and predict an expected forward rate of spread of a fire.

The alghorithms are well-known in the fire community: they've been published, they're accessible, and even today, it's relatively easy to apply the models using nothing more than a circular slide rule, which Sullivan noted is “still useful, because it's quite graphical and easy to use … but it's too slow if you have to make lots of predictions”. There also exist a host of spreadsheets implementing bushfire model algorithms, with “varying degrees of success, reliability and support.”

So one of Amicus' aims is to give people access to a consistent set of models and knowledge repositories; another, to make that data available to the modern user who's just as likely to be carrying a smartphone or tablet as using a PC in a control centre.

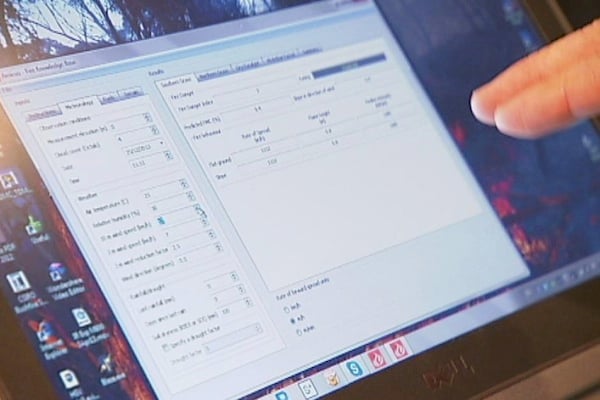

Amicus: fire modelling and knowledge for the future. Image: ABC, CSIRO

Another was simply to upgrade CSIRO's previous bushfire modelling software: built back in the days of Windows NT, Sullivan said, it's pretty much obsolete. So his team was able to get the internal funding to rewrite the software, providing an interface to bushfire data and models that works in today's environment.

In the long-term, however, the most important characteristic of Amicus will be the way it enables and encourages users to feed back their real-world experience against the models the software presents.

It's important to identify how the real world experience differs from the predictions of models, Sullivan said. As well as the chaotic complexity of a fire, he noted that there are still many fuel types in Australia for which no model exists.

Amicus users will be encouraged to help “crowd-source” their real-world experience back into the National Fire Behaviour Knowledge Base behind Amicus. For example, the information that the model's prediction ran two hours ahead of when a fire-front actually arrived will be a vital input to model refinement.

Images and videos taken by fire crews will also be a useful tool for researchers: they'll be able to compare time and location of an image to a model's predictions, and can also make estimates of things like fire intensity from the characteristics they see in user-generated content.

“That expands our knowledge of what to expect, based on real data”, Sullivan explained.

Interestingly, a lot of the programming talent behind implementing fire predictions in software came from people with flood modelling backgrounds – except, Sullivan said, the software writers complained about how different fire is from water. Water only flows downhill, and in a flood, there's no feedback loop between the water and the atmosphere, whereas high-intensity fires create their own localised weather, making modelling extremely difficult.

This is pertinent, given the current debate in Tasmania, where a government inquiry has criticised fire authorities for “ignoring” computer models in deciding how to deploy resources, during serious bushfires in January 2013. The report says that computer models predicted the fire would head towards the town of Dunalley, which it later did, destroying 63 homes, several businesses and a primary school.

While declining to comment on this directly, Sullivan said accuracy is a big challenge in fire modelling: the best models have as much as a 35 per cent error rate, so there's a big chance that any model prediction is going to be proven wrong.

Right now, he said, a model is “just one source of information. You can't just rely on a single prediction.” And that, he added, is what makes the user feedback role of Amicus so important for the future. ®