This article is more than 1 year old

Ding-dong, Cthulu calling: Infogrames’ 1992 Alone in the Dark

Crawling chaos in the classic classic house of horrors

Antique Code Show There was a time when you were considered a bit of a sissy if a computer game scared you. Yet along with the numerous innovations Alone in the Dark brought to the gaming world, it was one of the first titles to genuinely put the shits up anyone brave enough to play it.

Creaky floorboards, distant howls, Hitchcock camera angles, and an intriguing, hideous, unraveling plotline gave this title the power to spook like nothing before.

Behind you!

And if that’s not enough boundary pushing for one game, in time it would be seen as a key forefather for a distinctive gaming genre.

The brainchild of French developer Frédérick Raynal, Alone in the Dark’s characters and storyline took a great deal of inspiration from the work of American horror auteur HP Lovecraft, though the game itself was driven by Raynal’s love of 1980s horror movies. But the Lovecraft link was so overt that the original game box features a strap-line proclaiming the connection – presumably to reel in the horror fans while warding off know-it-all shouts of “rip-off!”

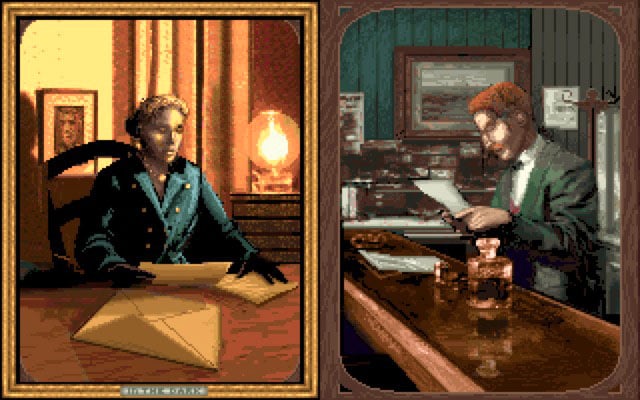

We start with the premise that the Louisiana manor of Derceto needs a thorough investigation after its owner, Jeremy Hartwood, dies in what is first presumed to be suicide. Choose between his niece, Emily Hartwood, or private investigator Edward Carnby – there’s no major difference in how the game plays, which I guess is a missed opportunity. But Alone in the Dark was released back in 1992 so it can probably be forgiven.

Pick your character: Emily Hartwood or Edward Carnby

While the quest begins as an investigation into the paranormal events of the manor, it rapidly turns into a struggle to retain your character’s own life. The story unfolds through discovered clues and letters, which is somewhat more interesting than the standard approach of breaking to a cut-scene whenever the story needs to be move on a tad. Undoubtedly, it also heightens the intrigue and scariness.

Alone’s development team were fully aware that PCs of the early 1990s were incapable of delivering a fully rendered horror house of visuals using nothing but polygons. The ingenious solution was to model characters and enemies in single colour-filled polygons entirely, while using digitised hand-drawn visuals for backdrops and a good deal of the room furniture.

Rooms were created in a specially written 3D tool which output a rendered image as the basis for the background art, and a data structure used for character collision detection.

Kick the ghoulies in the goolies

Fixed camera positions ensured that scenes remained technically feasible - and suitably realistic - with the camera frame switching as your character moved through each room or corridor.

The approach was a utilitarian case of working within technical limitations, but it gave the title extra spook value, with dramatic, film-like viewpoints – as though really being watched – aiding the atmosphere well.

Yes, it could be a little irritating when the frame changed in mid-fight or flight – making your controls re-orientate to the new camera angle – but it was a small price to pay for such accomplished visuals.

Relive the first level here, en Français, and alone in the dark if you dare…

Furthermore, Raynal’s bespoke 3D engine allowed polygons to be bent and warped, not simply repositioned, so more realistic movement and expressions for characters were possible. Limited in effect compared to today’s textured, bump-mapped and anisotropically filtered efforts, yet there’s still something quite suitably unsettling about those low polygon-count characters and their maniacal expressions.

Of course, Alone in the Dark’s unsettling atmosphere would have minimal impact were it not for the grandiose gothic musical interludes and spot sound effects, given enough importance by Raynal to be outsourced to an external sound agency, Sequence Coda.