This article is more than 1 year old

Delia and the Doctor: How to cook up a tune for a Time Lord

Making music from broadcast test equipment the Radiophonic Workshop way

The basis of basses

No doubt the precise definition of ‘electronic music’ will be the subject of debate long after the lights go out and the amps are silenced, but not all the sound sources were electronic. Even so, how they were handled was completely different to any conventional performance. Moreover, manipulation by electronic means – either by filtering, modulation or magnetic tape recording techniques – produced unique sounds that couldn’t be recreated by musicians alone.

Delia Derbyshire edits on a Philips EL3503, meanwhile

Desmond Briscoe checks the script

A case in point is the source of the distinctive tum-pet-ti-tum bass line which turns out to be a plucked string. Just how this initial tone was created appears to have been subject to misinterpretation.

One report mentions Derbyshire’s assistant, Dick Mills, as saying she used a blanking panel from a 19in rack unit. It seems plausible as this flexible metal strip could easily be twanged like a ruler on a desk to make a sound that could be varied in pitch. But we shouldn’t jump to conclusions.

Radiophonic archivist Mark Ayres apparently asked Delia personally and she said a plucked string and a rubber band. Incidentally, there are two bass lines – less noticeable is softer more electronic tone that’s somewhat plodding, having longer, sustained notes. That aside, other sources suggest that both the plucked string and the blanking panel were used but not in the way imagined. Apparently a string was tightened across the slightly bendy metal strip, then plucked and the sound recorded.

Breege Brennan’s thesis on Delia Derbyshire’s life and work highlights this method. By contrast, the BBC’s own reporting on the Radiophonic Workshop’s historic sound effects is somewhat ambiguous at first. At the end of the article is a video with Dick Mills pulling out a broken guitar and saying, “People might think we did Doctor Who on this, but we didn’t...”

In the presence of Ayres he then goes on to describe the technique: “It was just one of these strings on a piece of metal channelling that Delia twanged.”

Sampling, Sixties style

One way or another, that’s the initial bassline sound source taken care of, but it was the rudimentary sampling process that followed that really made it distinctive. There are pages and pages online going into the extraordinary detail but in short, the sound was recorded at various pitches. From this, tape loops were created and played to duplicate these tuned sections on another recorder. So Dick and Delia had lengths of tape with different tunings of the plucked notes to draw upon to compile the bass line.

Using well-worn tape splicing techniques – razor blade, edit block, chinagraph pencil and adhesive tape – these bass notes were, in effect, cut and pasted together.

In studios of the time and for years thereafter, tape editing this way was commonplace, but this would typically be on much longer sections. I recall putting together extended mixes by copying off instrumental sections to double the intro, extend a middle eight and or create a percussion break. At 30ips (inches per second), you get a lot of tape to play with as you rock and roll the reels to move the tape slowly over the playback head, listening out for the attack portion of a note or beat to chalk up as the edit point.

Editing on a tape recorder was the closest thing to a sampler in those days. Here, Delia Derbyshire plays a tape loop on a Philips EL3503. There were three available that were modified to all play in sync

Judging by the Radiophonic Workshop equipment list that Derbyshire had compiled from her early days there (which appears in her papers here), it seems the fastest they’d have been working at was 15ips and most likely on the Philips EL3503 machines that were favoured. It’s just as well really, as she took to chopping out the notes of the bassline, deliberately truncating them to give a more punchy sound.

Slower speeds would have been more of a challenge and the sections of tape would have been shorter too. Hence greater precision is required when marking up the edits and the smaller pieces of tape can be very fiddly, with sticking tape sometimes overlapping onto the sticking tape of neighbouring edits. Yet for all we know, the Beeb had her run the lot at 3.75ips to save tape.

Tape your time

Anyone can create sounds – whether they’re any good or not is another matter. That said, some sounds only really start to sound interesting when they’re treated with effects. Imagine hearing U2 guitarist The Edge without those dotted ⅛ note delays on his riffs, they’d sound extremely dull if those cascading echoes weren’t there to busy things up. In this YouTube clip he demonstrates his technique.</p?

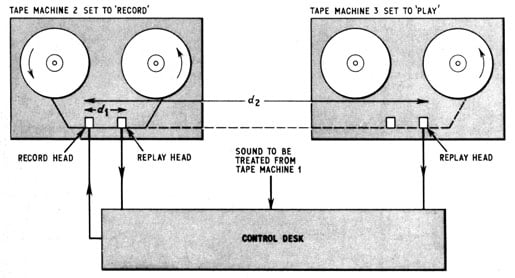

Tape loop echo configuration with two machines

Likewise, the whooping synth noises in the Doctor Who theme would lack atmosphere without those supporting echoes that repeat its strange electronic tones, adding a sense of spaciousness to the melody line’s impact. With no sampling to create digital delay lines, the effect was created using a tape loop that could be fed through several tape machines. The initial recording would then be replayed over multiple tape heads, the spacing between them creating the delay time. The timing of the echoes could be varied by simply changing the tape speed.

Dedicated tape loop echo units did exist at the time, such as the Watkins Copicat, but the Radiophonic Workshop’s grow-your-own method and almost certainly delivered a higher fidelity effect. Moreover, the tape machines were frequently used as an effect, with simple changes such as reversing a tape or changing its speed producing useful results.