This article is more than 1 year old

Sinclair’s 1984 big shot at business: The QL is 30 years old

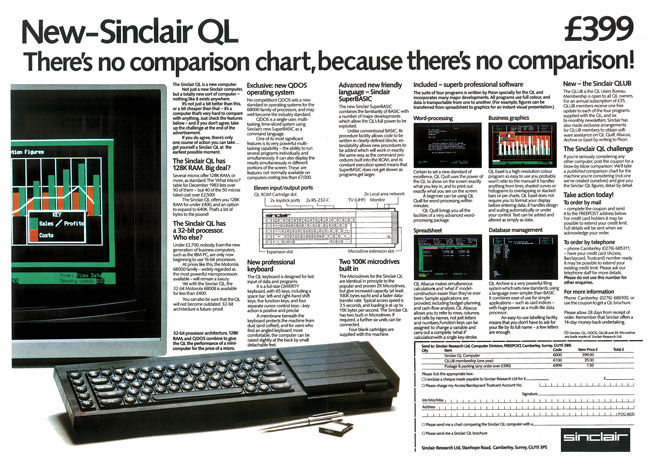

Quantum Leap micro leapt too early

Delay after delay

That the QL subsequently failed to appear as promised was bad enough, but worse, customers were out of pocket. In an attempt to cap the growing flow of bad publicity, not to mention the growing interest in the saga of the Advertising Standards Authority, Sinclair promised to put the money into a “trust fund” and pledged not to touch the cash pile until the first QLs were despatched.

That didn’t come as much relief to waiting buyers, who quickly calculated how much interest the account would generate for Sinclair while they were left waiting. Sinclair at least allowed them to cancel their orders and get their money back. But very few seem to have taken the company up on its offer.

By the middle of March, eight weeks after Sinclair began taking orders, no QL had shipped. Officially, QDOS was taking longer to finish than expected and one of the QL’s two ULAs required further modifications. The latter claim is probably true, but Tony Tebby insists QDOS was ready to go and able to be committed to Rom along with SuperBasic in March 1984.

And they would not, he adds, have required the infamous QL dongle.

According to a Sinclair spokesman, the QL’s firmware was too big for the Rom. The QL could take 32KB of Rom internally, and QDOS and SuperBasic now took up 40KB, mandating a 48KB Rom chip.

Rubbish, says Tony Tebby. The QL was always specced for 64KB of Rom and, from January 1984, the PCB design incorporated two Rom slots, each able to take 8, 16 or 32KB Rom chips. The machine ought to be able to have a 16KB and a 32KB Rom chip fitted. Why, then, bother with the dongle, an inherent admission that the machine was flawed?

Because Sinclair felt it better to send out QLs that worked, sort of, than to delay the product even further in order to await fully working ones. It was easier to blame failures on software than it was to confess that the hardware still wasn’t ready. Duff software tacitly implied a better version in the works. Not wanting to accept that they’d coughed up for duff hardware, punters naturally believed the white lie and didn’t bat an eyelid when Sinclair did in fact replace their machines in due course.

‘White lie’? It seems that way, because the first QLs shipped with an early, pre-release, test version of the OS, ‘FB’, even though a working version, ‘JM’ had already been completed by this point. The dongle conveniently indicated which returned machines should be replaced rather than repaired.

Sinclair Radionics and now Sinclair Research had been adhering to a theory that it was better to ship and fix problems by sending out replacement products, than by delaying a product to get it right. Sinclair companies had never gone in for much in the way of pre-shipment production development; once a devices was out of the labs it was considered ready to build and ship. Only then would production improvements be sought.

Driving toward completion

March 1984 came and went and with it Sinclair’s second, revised deadline for getting the QL into buyers’ hands. By now punters were being told they would receive their machines by the end of April. Sinclair made it - just. It was claimed only a few dozen QLs shipped on Monday, 30 April, every one delivered to their new owners by taxi or Sinclair staff driving hire cars. Buyers who had had to wait were given a £15 RS232 printer cable for free.

A Sinclair spokesman called this a “goodwill gesture”, but irate buyers felt it was the least the company could have done given not only the delays but how buggy the new machine now appeared to be - thanks to early draft hardware and the aforementioned inclusion of a test version of the OS. “Shoddy finish and unloadable software seems to be the least of their problems,” wrote Your Computer in its June 1984 issue (published in May 1984). “The Screen Editor can make the system crash and the promised real-time clock is missing - along with the manuals.”

The RTC would never appear: the ZX8302 chip, one of the QL’s two ULAs, would have had to be modified to cope with a 68008 bus access bug which manifested itself during resets. It was easier to drop the battery and stop mentioning that the QL had a real-time clock.

David Karlin is tactfully restrained when it comes to discussing his personal feelings about the QL development process - except in his criticism of the Microdrive, which is the part of the system that caused the most headaches and, for him, ultimately sank the machine. He has a point. Most of the complaints raised by reviewers and users centred on the unreliability of Sinclair’s tape-loop system. The Spectrum version was finally released a year late, in August 1983. The version in the QL would need much improvement if it was to be seen as a viable alternative to floppy disks.

The back of the QL: (L-R) 3.5mm audio jack-style networking ports; power; monitor; TV; original, phone-style serial and joystick connectors; Rom slot. Click for a larger image

Source: Ewx

According to Rick Dickinson, “the Sinclair way” of doing things meant that rather than redesign the Microdrive internal chassis for the new computer, the Spectrum drives were simply put into the QL case.

“With different materials it would have been more reliable,” he says. “I wanted to start off with a brand new chassis in a different material and build the two microdrives on that, but they insisted that now we’d already tooled up a chassis, we’d just have to use that. And of course what would happen is that, because you’re going into a whole new case with a whole new set of parameters, you’d screw the microdrive chassis in and the torque reaction from the screws would twist all the boxes slightly and just slew the whole chassis - both of them - off at one degree.”

And with the mechanical design set in stone, all Sinclair engineers could do to enhance the Microdrives for the QL was to devise a new way to arrange data on the tape, up the speed and adjust the electronics.

“We needed to design a Phase Lock Loop (PLL) circuit to decode the magnetic signal that’s coming off microdrive and track speed variations and such,” recalls David Karlin. “Mixed analogue stuff was difficult and expensive and didn’t mix with some of the other gate-count requirements of CMOS technology, so I opted to go for a digital PLL. I had a conversation with Ben Cheese, the analogue engineer doing the Microdrive, and I asked what’s the duty cycle of the waveform how far away from 50 per cent will it be, and Ben said it’ll be very close to 50. So I went and designed a digital PLL which would work fine if the duty cycle was between 45 and 65 per cent.

“But that wasn’t right. The duty cycle could actually vary between 10 and 15 per cent rather than just five per cent. So apart from the mechanical problems inherent in the Microdrive anyway, the duty cycle was not matched to the PLL and the only thing that could be done by the time this was to try and really sort out the analogue electronics to get the duty cycle to 50 per cent. Ben did a heroic job, but it was a losing battle, so we ended up with an unreliable mass storage system and in my view that’s what killed the product.”

Reaching ‘QL 1.0’

The other issues were largely solved during the first six months of 1984, either with hardware updates – production specs were changing on a monthly basis, though the PCB was updated only a few times, up to Issue 5 – or through software workarounds. Not every fix was successful: beating a glitch on the ZX8301 which emerged when it got hot minimised the bug’s impact on Microdrive usage but at the cost of killing network compatibility with the Spectrum’s Interface 1.

By July, Sinclair was no longer having to bundle a Rom dongle – the QL’s now coming off the Datatech production line were build ‘D06’. Come the end of the month, Sinclair said it would soon begin asking for original, dongle-supplied QLs to be returned, free of charge for a Rom swap. The old machines were junked and simply replaced with D06 or later QLs.

“Our intention is to stagger the recall of machines, and as yet we do not know how long customers will be without their QLs when recalled,” a spokesman admitted. The ‘Rom-swap’ recall process began in August, by which time the company reckoned the turnaround time would be ten days.

By this point, many different versions of the language had shipped, internally dubbed ‘FB’, ‘PM’ and ‘AH’. ‘FB’ was the version that went out on the first QLs. ‘AH’ was, a spokesman said in July 1984, the “final version”. It wasn’t, says Tony Tebby, though it was the point at which there would be no new additions made to SuperBasic, only bug fixes. The true ‘final’ version of the firmware was ‘JM’, which was tested and ready by March 1984, Tebby says, though it wasn’t used in shipping machines until July 1984.

‘JM’ was followed after a few weeks by ‘TB’ and soon a new development version, ‘JS’, was established, after which Tony Tebby finally left Sinclair. It wasn’t ready for release, yet it formed the basis for US QLs because, claims Tebby, Sinclair staffers couldn’t find the ‘TB’ source code. ‘JS’ was ultimately followed by ‘MG’, which formed the basis for the first non-English QLs, in 1985.

In the Autumn of 1984, Sinclair began releasing the QL to its retail partners. By now the production spec was at build ’D14‘, featuring the latest motherboard, Issue 6, which added an extra TTL chip to cope with issues found in the ZX8301 ULA. The QL hardware was at last in a ‘1.0’ state. Future build updates were made to improve yields not tweak the basic design. The manual, largely written by Roy Atherton of Bullmershe College Computer Centre, but incorporating material by Sinclair staff programmer Steve Berry and Psion’s Dick de Grandis-Harnson, was now complete too.

The TV output’s high-frequency oscillator had been moved away from the left-hand Microdrive’s head amplifier to stop interference causing read problems that could, at worst, render the drive inoperative. On the drive itself, a capacitor had been placed in parallel with the head to block noise induced by the drive’s motor. The 1980s phone-style connector used for the joystick and serial ports was replaced with a nine-pin D-Sub: male for the joystick ports, female for the serials.

Getting the QL into shops allowed Sinclair the luxury of essentially relaunching the QL. It began booking television ad space for a commercial designed to establish the QL as a much more economical alternative to its key rivals: the IBM PC, the Mac and the BBC Model B, the latter priced up from £399 to £1632 by adding a pair of 5.25-inch floppy drives, a monitor and more. By contrast, the QL, pitched with the colour monitor David Karlin always wanted it to have came to £698.

The Microdrive mistake

And yet, there were still issues with the machine - most, but not all, due to its storage system. “The manager of the local branch of Dixons told me that out of 1000 machines delivered to their warehouse, only 190 worked properly,” claimed a Sinclair User journalist in November 1984. “Further rumbles from Spectrum distributors seem to indicate similar troubles, with one hapless dealer spending a whole morning with six QLs and six sets of Psion software trying to find a combination that allowed all the Psion wares to be loaded.”

One of the QL’s two ULAs, the ZX8301, contained the display generator but no buffering on the lines to the RGB monitor output. Yanking the screen cable while the computer was powered up could damage the chip, which then had to be replaced. Not so much a bug, this, more a product of keeping costs low. And was it unreasonable to assume that most users would leave their displays connected? That said, the TV output’s timings were off, causing overscan issues.

“The one really bad bit of cost-cutting I did was trying to squeeze two serial ports out of one,” David Karlin concedes. “That was not a sensible thing to do, and we should have just said it had one serial port. It was only one serial port, so the two we claimed had to be multiplexed and that was seriously not a good idea.

“Because you’ve only got an 8-bit bus - pin count issues again - you have to slow the main processor in order to allow the graphics [circuitry] to get at the memory... But if you put your extra memory in, then the memory that wasn’t shared with the video bus was suitably fast. It was really only if you had the version with just the one bank of memory chips that the video slowed the computing down to a disappointing degree.

“It was undoubtedly the case that the 68008, by the time you’d doubled up one the bus cycles and you’d taken a whole load of cycles away to run the memory, it was slower than we’d have liked. But those are tiny issues - what really mattered was that we didn’t have a reliable mass-storage method.”

There was no shortage of QL add-ons - especially for storage

CST (right) went on to make its own QL. Click for larger image

Or one that software developers were keen on. In May 1984, Nigel Searle talked to the press about a Sinclair charm offensive aimed at persuading software developers to support the QL. Psion was already on board, of course, and Searle said he was now talking to Quicksilva, Melbourne House, Ultimate and Picturesque in the UK, Digital Research, Microsoft, Lotus, Ashton Tate and Software Arts in the States. He said he wanted 50 titles out by the end of 1984. When that date came round, there were actually fewer than ten.

Even had the Microdrives been reliable, only Sinclair could produce them, and they were proving far less robust than cassettes when it came to high-speed duplication. Making them wasn’t easy - in a May 1984 interview Searle said Sinclair was then punching out 100,000 a month with an eye to ramping up to 40 million a month at some undefined point in the future. It almost certainly never achieved that.

Software scarcity didn’t help sales any, and nor did the reputation for fragility and instability gained by those early, prematurely released models. A WHSmith spokeswoman said at the end of 1984 that sales had been “very slow” thus far; “disappointing” was the word used by a Boots spokesman. Estimates in the press put the number of QLs in users’ hands at just 40,000, a fraction of the machine’s potential audience. None of Sinclair’s promised add-ons, among them a 512KB memory expansion module, a hard drive interface and a modem, had yet materialised.

Moving on

At the start of 1985, David Karlin decided to leave Sinclair Research. Tony Tebby had made good on his promise to leave when the QL was in what he regarded as a fit state to ship to customers. Jan Jones, by then expecting her first child, left soon after.

Having build a micro from the ground up, Karlin now wanted a fresh challenge and a more commercially oriented one. He wanted to go into business for himself, he says, but was persuaded to stay by Nigel Searle, who put him in charge of manufacturing. He found it in a poor state, he says. The company owed money to its key contract manufacturers, Timex and Thorn-EMI Datatech - the latter, with Samsung, was also producing QLs, and its cashflow was precarious. Karlin spent the next 12 months making sure the bills got paid and the right number of orders placed.

Karlin replaced Production Director Dave Chatten who, in March 1985, was made joint MD with Bill Jeffrey. Chatten was a long-time Sinclair man, but Jeffrey was an outsider, having joined the company from Mars Electronics at the start of the month. Nigel Searle was sent to the States to run Sinclair’s US wing, which he had himself established in 1980 before being brought back to the UK in 1982 to take over day-to-day operations here.

But Searle didn’t take the QL with him straight away – Sinclair formally announced it was again delaying the machine’s US debut, originally planned for the previous Autumn. The management reshuffle had been prompted by Sinclair Research’s ailing finances. Its income had been hit hard by the slowdown in home computer sales and the costs of Sir Clive’s Wafer Scale Integration and C5 projects. By the summer of 1985 it looked like media tycoon Robert Maxwell might buy Sinclair for £12 million. The deal fell through: thanks to a massive product order commitment from Dixons, Sinclair’s desperate need for cash was postponed.

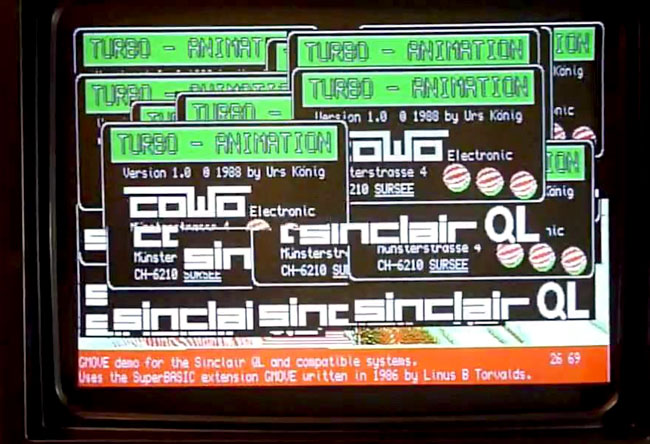

Demo software from one of the QL’s most famous users: one Linus Torvalds

Now there was even talk of a new QL and the idea of a new Spectrum based on QL technology was revived, though the machine behind the rumours in the press was the upcoming Spectrum 128, an upgraded Z80A-based machine with 128KB of Ram and souped-up sound, all developed with Spanish money.

ICL’s One Per Desk had already arrived too, early in 1985, following a November 1984 launch. ICL took the core QL, complete with a pair of Microdrives, built in a modem, a phone and an answering service, and pitched it at business for £1195 a throw. But that’s another story. For now, it’s enough to say that in January 1986, the OPD won a Recognition of Information Technology Achievement award for the Systems Innovation of the Year. The win echoed the QL’s victory in the British Microcomputer Awards the previous July as Microcomputer of the Year. Some folk, at least, could look past the QL’s early problems to see its potential.

But the potential was never realised, primarily thanks to the inclusion of the flawed Microdrives. Even the much-criticised keyboard doesn’t appear to have put people off the way many an early reviewer feared it might. The QL 2 never appeared and neither did a rumoured business machine codenamed ‘Enigma’ or possibly ‘Tyche’ which was claimed to run Psion’s xChange out of a Rom that also included the Gem GUI.

If this machines ever existed as anything more than a broad concept being aired at Sinclair Research, it was cancelled in April 1986 when the company’s finances finally hit rock bottom and Sincair Research was sold to Amstrad for £5 million, less than half what it was considered worth the previous summer. One of the first things new owner Alan Sugar did was knock the QL on the head. Quite apart from the QL’s sales performance to date, Amstrad was doing very nicely thank you selling its low-cost, business-centric, highly integrated PCW 8256. Sugar also made lots of Sinclair Research people redundant, among them David Karlin.

By this point, some 139,454 QLs had been manufactured, at least 122,793 by Thorn EMI Datatech for the UK market and 16,661 by Samsung for Europe and the US.

Life after death

But the machine had its fans. One was a Stevenage-based company called CST run by David and Vic Oliver, who had set up shop making QL add-ons. With engineer Graham Priestley they devised a machine called Thor that was based on QL motherboards they found they could obtain directly from Samsung. They also tweaked QDOS to support the machine’s one or two floppy drives – configurations priced at £599 and £699, respectively. There was a 2OMB SCSI hard drive model too; it cost £1399. The Thor was quickly dubbed ‘The Son of QL’ in the press.

Citing its ownership of the QL intellectual property, Amstrad soon forbade the use of the QL name and QL components. There was briefly talk of an attempt being made to buy or license those rights from Amstrad, but there’s no sign that Amstrad was persuaded to part with them. Psion was more forgiving, and licensed Quill, Easel, Abacus and Archive to CST, its Danish sales partner Dansoft and its UK distributor Eidersoft.

The Thor went rapidly through a number of configurations before the Thor 20 appeared with an entirely new motherboard: clearly, CST was successful in persuading Samsung to produce compatible kit. However CST pulled it off, it demo’d the Thor at various computer shows in 1986 and 1987, and is believed to have even shipped a small number to buyers, all without interference from Amstrad. But too few were sold to allow CST to continue as a going concern and production appears to have ceased in 1988.

Separately, Tony Tebby designed a second-generation QL with the help of ex-Sinclair engineer Jonathan Oakley. After leaving Sinclair himself, Tebby had formed QJump, a software company dedicated to producing QL apps and utilities. He found potential backers for the project, but when it came to the crunch, they couldn’t or wouldn’t stump up the £250,000 Tebby needed to realise his design as a shipping product.

Tebby maintained his connections with the QL world, initially offering add-ons for Q-DOS and SuperBasic, and later recreating Q-DOS for the 68000-based Atari ST as SMS2. This was later re-released as SMSQ for Miracle Systems’ QXL, a 68000 add-on board for PCs. He is still a figure in the QL enthusiast scene.

After leaving Sinclair shortly after Tebby did – she was expecting her first child – SuperBasic writer Jan Jones devoted herself to raising her family. She’d always had a love of writing - she penned a book about SuperBasic – and alongside looking after the kids, she took up short story writing. She went on to become an award-winning writer of romantic fiction.

David Karlin took his redundancy money and founded the business he’d wanted to start in 1985, hardware company Alfa Systems. It created the DiskFax, a rather popular (with spooks) gadget for quickly duplicating floppy disks over phone lines. He went on to run audio company Harman International’s UK operation and was later a Managing Director at accountancy software company Sage. These days he runs Bachtrack, a global search engine for live classical music events. ®

The author would like to thank David Karlin, Tony Tebby, Jan Jones, Rick Dickinson and Jonathan Oakley for their kind help in the preparation of this article. QL aficionado Urs König has a site devoted to the machine’s 30th anniversary, here