This article is more than 1 year old

Apple’s Mac turns 30: How Steve Jobs’ baby took its first steps

Part 1: Love it or loathe it, the Mac shapes every nook and cranny of your computing life

Feature Thirty years ago this Friday, at approximately 9:45am on Tuesday, 24 January, 1984, the Macintosh introduced itself after Steve Jobs unveiled it at an Apple shareholders' meeting in Cupertino's Flint Center for the Performing Arts.

"Hello. I'm Macintosh. It sure is great to get out of that bag," the odd-looking 16.5-pound box said in its robotic text-to-speech voice, based on the Apple II's Software Automatic Mouth, the precursor to MacInTalk.

History is made of such moments – identifiable points in time before which something wasn't, and after which something was.

On the afternoon of Sunday, 20 March, 1983, for example, Jobs famously said to then–PepsiCo headman John Scully, "Do you want to spend the rest of your life selling sugared water or do you want a chance to change the world?" In one moment, Apple changed direction – as did not only the future of the Mac but also the career of Steve Jobs.

A few months later came another pivotal moment: at 10pm on an August Sunday, Mac programmer Steve Capps hoisted a pirate flag painted by Mac icon-designer Susan Kare onto the roof of the Bandley 3 building on Apple's Cupertino campus.

Before that night-time roof raid, the Macintosh division was essentially indistinguishable from other Apple workgroups in an increasingly bureaucratic company, one that was struggling to deliver on its commitment to the costly Apple Lisa and its game-changing GUI, the Mac's precursor. After the Jolly Roger flew, however, it was clear to all onlookers that the team was guided by one of Jobs' maxims: "It's better to be a pirate than join the navy."

The original Macintosh team, the original pirate flag, and the original Steve Jobs (lower right)

The thirty years since have seen many memorable moments in Mac history, some which brought good news to the Apple faithful – think System 7's introduction on the morning of 13 May, 1991 – and some which led in the opposite direction, such as the board meeting called hastily at 7am on 17 June, 1993, during which Apple CEO Scully was ousted and replaced by the arguably disastrous Michael Spindler, who nearly flushed the Mac maker down the toilet.

The Mac's ten-thousand, nine-hundred, and fifty-nine days have seen many decisive moments, but we've selected a mere 10 that we think are especially noteworthy. You'll likely disagree with some of our choices and have some alternate suggestions of your own – we'd love to read about them in the comments.

There can be no argument, however, about the Mac's significance in the history of personal computing. Supporter or detractor, you must admit that Apple's pioneering mass-market point-and-click PC has indisputably changed how we all interact with the digital world during the Mac's first 30 years.

As for the next three decades, well, your guess is as good as ours – but here's our countdown of the 10 most influential moments that have shaped the past 30 years. Happy Birthday, Apple Macintosh.

9am Friday, 16 May, 1997 – Steve Jobs seduces Mac developers

Steve Ballmer can rightly be faulted for his stumbles during his tenure as Microsoft CEO, but in perhaps his most famous performance in that role, he was spot on: when it comes to a platform's success, it all boils down to "Developers! Developers! Developers! Developers!"

But for Jobs, the focus was not on coddling developers by giving them exactly what they wanted. That wasn't Jobs' style. He could pull the rug right out from underneath them, destroy years of their work, and still manage to seduce them into The Macintosh Way.

Case in point: how he handled developers' outrage when Apple killed off OpenDoc, the document-centric software technology that asked developers to write small "parts" that could be pulled into documents to add bits of functionality. OpenDoc was part of a major, seven-year OS-redesign effort into which Apple – and scads of developers – had poured tremendous blood, sweat, tears, and resources.

Shortly after Jobs returned to Apple in early 1997, he strangled OpenDoc in its sleep – or, more specifically, he convinced then–Apple CEO Gil Amelio to do so.

On the morning of 16 May, 1997, during the closing keynote of Apple's Worldwide Developers Conference, Jobs entertained questions from the assembled developers. Apple's stock had closed that day at $4.31, down from $7.10 one year before and $10.94 the year before that. Apple was sinking; developers were bailing.

The first question was about the demise of OpenDoc. "I know a lot of you spent a lot of time working on stuff that we put a bullet in the head of," he answered. "I apologize. I feel your pain. But Apple suffered for several years from lousy engineering management. I have to say it."

The developers applauded.

"There were people going off in 18 different directions, doing arguably interesting things in each one of them," Jobs said. "Good engineers. Lousy management."

The Cyberdog browser, one of the few fruits of Apple's aborted OpenDoc effort

Jobs told the developers that he knew that he was going to "piss off people" by killing some longstanding projects such as OpenDoc, but that Apple had "had its head in the sand for the past many years."

One developer was having none of the kumbaya happy talk. When his turn at the microphone came, he quietly tore into Jobs. "It's sad and clear that ... you don't know what you're talking about," he told the Apple co-founder.

Jobs' five-minute response was a textbook case of using self-deprecation as an argumentative strategy, admitting ignorance without giving an inch, and winning the hearts and minds of an audience while doing so.

"Some mistakes will be made, by the way, some mistakes will be made along the way," Jobs said. "That's good, because at least some decisions will be made along the way. And we'll find the mistakes, and we'll fix them." Again, the developers applauded.

"Some people will be pissed off. Some people won't know what they're talking about. But I think it is so much better than where things were not very long ago."

He had 'em. They stayed – and some of them became very rich. Eventually.

Monday morning, 2 March, 1987 – The Mac II reverses Apple's fortunes

The original Mac 128K, 512K, and 512Ke were closed systems. Not only were they not the type of computers that would attract a business clientele – the IBM PC, released years before on 12 August, 1981, had that market sewn up – but they were also failing in the broader market.

Simply put, Jobs had been wrong: his idealized "toaster" of a closed, expensive-but-limited computer was not catching on among the general public, and the failure of the Macintosh Office, announced in January 1985, did nothing to move the Mac into the business world.

Too bad, Steve. Ater a power struggle with CEO John Sculley, Jobs was removed from the leadership of the Macintosh division. He soon resigned.

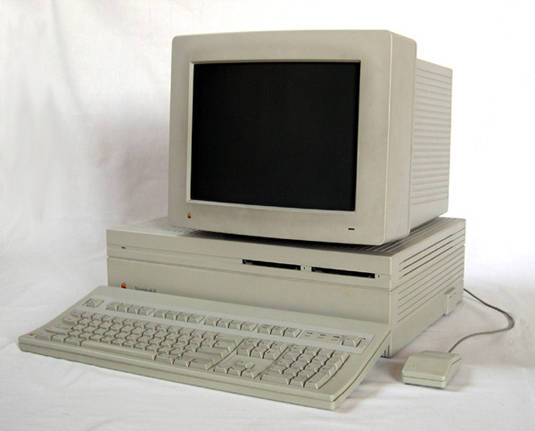

The keyboard, by the way, wasn't included in the $5,498 price for the 1MB RAM, 40MB hard-drive model

In January 1986, the Mac Plus was introduced. It added limited expandability through the addition of a SCSI port, but it was hobbled by the same 8MHz 68000 chip as were its predecessors. To be sure, it attracted more market acceptance than did its forebears, but not sufficiently in business – or, for that matter, in what would become the Mac's saviour, desktop publishing, despite the introduction of the LaserWriter on 1 March, 1985 and Aldus PageMaker for the Mac, also in 1985.

On 2 March, 1987, Apple released the Macintosh II (along with the Macintosh SE), and everything changed. Saying that the Mac II was a volte-face would be putting it mildly.

Most notable, perhaps, was the fact that the Macintosh II was expandable, thanks to its inclusion of six NuBus slots, a system developed at MIT and implemented in the Mac II in a 32-bit, 10MHz configuration. NuBus, by the way, remained the Mac's expansion slot of choice until Apple released the PowerPC 604–powered PowerMac 9500 in May 1995, which brought the industry-standard PCI bus into the Cupertinian fold.

But it was also the Mac II's processor that moved the Mac beyond its "sure it's innovative, cute, and easy to use, but what can I do with it?" status. Instead of that 8MHz 68000, the Mac II had a comparatively speedy 16MHz 68020 coupled with a Motorola 68881 floating point unit (FPU).

Although the Mac II is often referred to as the first colour Mac, it really wasn't, per se. It was merely "colour capable", with Color QuickDraw (PDF) in ROM. There was no graphics chippery on its motherboard – it needed a graphics card installed in one of its NuBus slots to drive its display, which Apple was happy to supply.

Development of the Mac II, it has been reported, was begun before Jobs left and without his knowledge. If true, that skunkworks project proved that there were still Apple engineers who lived by Jobs' earlier renegade credo.