This article is more than 1 year old

Loki, LC3 and Pandora: The great Sinclair might-have-beens

The ‘Super-Spectrum Entertainment Engine’ and more

Pandora

Sir Clive Sinclair had wanted to build a portable computer for years, and Sinclair Research had engineers looking into the notion of an untethered machine as far back as 1981. It even steered his thinking about the Sinclair Radionics micro, which (eventually) became the NewBrain. Sinclair would eventually release a portable, Cambridge Computer’s Z88, in 1988 - essentially his take on one of the earliest mobile computers, the slab-like Epson HX-20.

The Pandora was entirely different: a clamshell machine with not an LCD screen like the HX-20 or the Z88 but one of Sinclair’s two-inch flat cathode ray tubes. Based on the Z80 processor, Pandora would be compatible with the Spectrum, early rumours leaking out of the company indicated, and would include a Microdrive. It would, like the QL, come bundled with productivity software, stored on ROM.

It would, in Clive Sinclair’s mind, entirely replace the owner’s current computer: “We have to come up with a portable which people will be happy to use as their only machine - so that they won’t have need of any other,” he said in an interview with Popular Computing Weekly in February 1985. “Swapping files from one machine to another is just not on - the data has to be there all the time.”

It would, he hoped, be a true first for Sinclair Research: a computer that was not only genuinely portable – as the HX-20 was but the Osborne 1 certainly was not – but also usable. It had a decent-sized display, which, again, machines like the Epson and the Osborne lacked. It would ensure that the Sinclair reputation for innovation, bruised by the QL, would be seen to be as healthy and as active as it had once been.

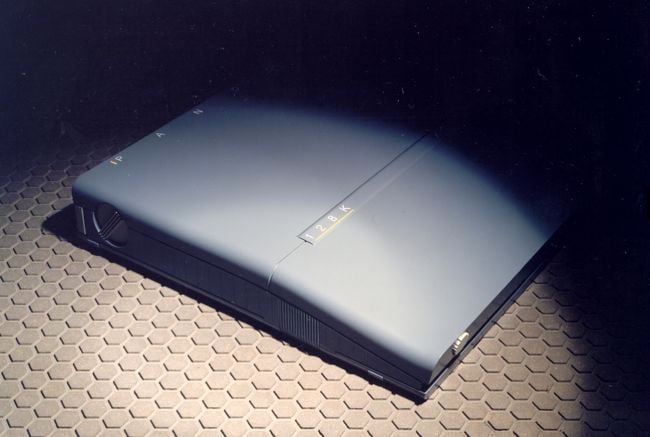

One of the first Pandora mock-ups, built to demonstrate the optics, not as a working computer

Source: Rick Dickinson

“The resultant virtual image has a residual curve which the eye interprets as a 3D surface reminiscent of a Cinemascope screen,” Perran Newman is said to have written in a Pandora progress report in January 1986.

That sounds impressive. The Pandora’s display was a Sinclair flat tube fitted into the lid. It was, of course, far too small to make a usable text display on its own, so Sinclair engineers contrived an arrangement of mirrors and lenses which folded out as the computer’s lid was lifted. The notion, says Stephen Berry, who worked on the computer’s software, was that, the tube’s image was reflected and magnified into a “floating” image placed where a modern laptop’s screen would be.

Stephen says one problem was that in order to see the virtual image, the user needed to focus his or her eyes at infinity, even though the screen appeared close up. It was like trying to see those 1980s ‘magic’ pictures, which embedded pictures inside repeating patterns. Only by trying to focus your eyes ‘behind’ the picture could you see the hidden object. It wasn’t easy to do; distracted, your eyes didn’t automatically focus on the image but rather on the poster itself. The Pandora screen was much the same.

Rupert Goodwins said of it: “I did the screen driving software and designed some fonts – the screen was so weird that if you didn’t have fonts explicitly matched to it, the chances of reading stuff was minimal – all tested on an old Zenith green monitor I’d jimmied to match the aspect ratio of the final screen.”

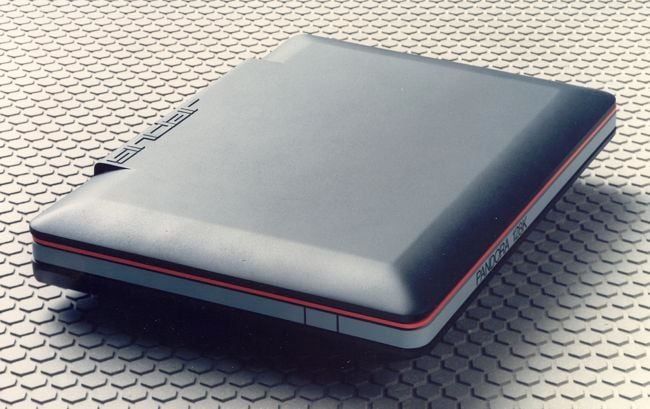

Pandora’s industrial design when through a number of iterations, first as sketches made by Sinclair’s designer, Rick Dickinson, which led to a final design that was modelled as a physical reproduction. This was subsequently revised, at least once if not twice.

Box clever

“Only a couple of prototypes got made,” recalled Goodwins. “The circuit never got further than a collection of breadboards, and the models were there to test the optics and screen details. People were understandably nervous about things like the extra-hight tension supply to the overdriven tube, and even more nervous about whether the whole thing would either work or be manufacturable.

“I can’t remember too much about the video modes, although I think there was one that had 64 x 24 characters. That was going to be the main one, because Pandora was seen as a productivity tool rather than a games box. It also had a 6 or 8MHz Z80 - I think it was the Hitachi variant with some extra instructions - and everything else bar the memory in one ULA.

“I also seem to remember that it wasn’t going to have Microdrives: the flat screen was seen as quite enough nonsense to be getting on with, thank you very much, Clive.

“Journalist Guy Kewney asked Alan Sugar whether he’d bought the rights to Pandora. ‘Have you seen it?’ asked Sugar. ‘Yes,’ said Guy. ‘Well then.’ said Sugar.”

Amstrad would, just a few years, release the Notepad NC100, a rather less sophisticated Z88-alike.

A later Pandora design revision

Source: Rick Dickinson

Clive Sinclair never lost his vision for a workable portable computer, and almost immediately assembled a team to work on a machine without Spectrum compatibility. Goodwins was asked to participate, but chose to work for Amstrad instead; he was one of very few Sinclair people to be hired by Sugar’s firm. No Spectrum support, then for the Z88, and no flat tube, either. Sir Clive was persuaded that perhaps LCD - a technology he detested, says Stephen Berry, because of the of carcinogenic chemicals used in its production - had to be adopted after all.

The architecture remained as it had in Pandora: Z80 CPU plus ROM plus RAM plus one ULA. Ditto the use of disposable rather than rechargeable batteries, Sinclair long having averred that you could always buy fresh batteries but rarely find a power outlet to feed a charger.

The ROM contained a new OS, OZ, plus PipeDream, an integrated word processing, spreadsheet and database program. It also contained a version of... BBC Basic. At long last, Sir Clive had laid a very specific ghost to rest.

QL 2.0: Enigma, Tyche, Proteus and Janus

During the latter part of 1985, Sinclair Research seems to have been awash with ideas about how the QL line could be extended - or, given the QL’s blemished reputation, caused by announcing the original far too early - another brand but one also aimed at a more sophisticated audience than the Spectrum.

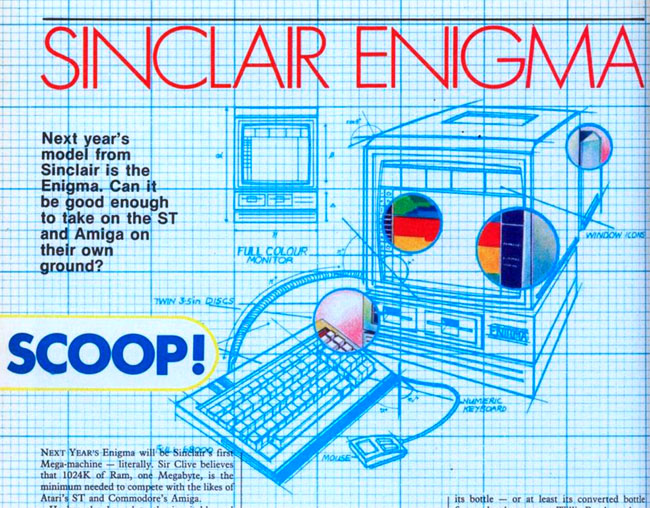

"Enigma" emerged in the Autumn of 1985: a system with one or two 3.5-inch floppy disks in a system unit which would come with a bundled colour monitor, printer and a separate keyboard. It would, claimed Your Computer, feature 1MB of RAM and bundle versions of the Psion-produced QL productivity applications in a “full Window, Icon, Mouse environment”, perhaps Digital Research’s Gem, which had been released in the UK the previous April.

Your Computer lauds ‘Enigma‘

In many ways, Enigma can be seen as Sinclair’s response to the PCW 8256, Amstrad’s Z80-based "word processor" launched in September 1985 and quickly becoming hugely popular. The QL’s hardware designer, David Karlin, had wanted the QL to be a machine along the lines of the QL. Perhaps Enigma was his suggestion for a way for Sinclair to release not only a PCW rival but a machine closer to the one he’d wanted to make in the first place.

Enigma was rumoured to be set to ship toward the end of the first half of 1986. Was it ever a runner? It was rumoured that the creator of the Archimedes casing had designed the box for Sinclair but sold the design to Acorn when Sinclair changed its mind. If not Enigma, then the case might have found a home as an IBM PC clone, which company executives were also pondering as the money began to run out during the latter part of 1985 and the situation at Sinclair Research began to look increasingly untenable. Stephen Berry says the PC clone was "Dylan".

"Tyche" is another QL successor and perhaps has more weight than Enigma because it eventually made it outside Sinclair, at least in the form of an updated ROM image developed by Jonathan Oakley and made public many years later. Thanks to the Amstrad takeover, the Tyche code became Sinclair’s final version of QDOS, though it was never released at the time.

It is said to have been prepared not for the QL but for a successor that has been described by QDOS creator Tony Tebby - though he had been long gone from Sinclair by then - in terms that sound a lot like the Enigma description.

“There was a program internally to do a QL-type machine, that’s to say based on the same chips, but with disc drives,” said Sir Clive in 1986. “It wasn’t really a QL, though, and it was a much more expensive machine.” That sounds a lot like Enigma/Tyche.

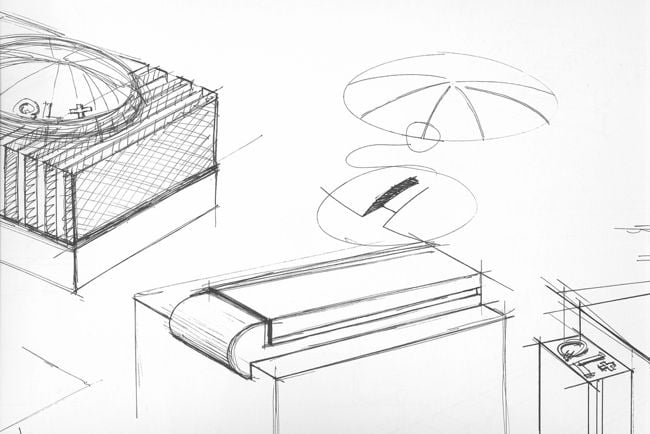

How a second- or third-generation QL might have looked

Source: Rick Dickinson

Janus remains something of a mystery. The god Janus had two faces, to look two ways at once, and it’s tempting to see that reflected in a concept machine able to succeed in both the business and the games markets - perhaps the way it had once been thought that the QL might go. Equally, and perhaps more likely, it reflects looking both forward and backward: the latter in its support for QL technology, but forward to a new world of computing based on Sinclair’s wafer-scale integration ideas.

Certainly designer Rick Dickinson sketched and produced mock-ups of a number of wafer-scale machines, some in upright towers, others in squat, domed units. Many are marked “QL+”. Was Janus and the QL+ one and the same thing, and if so were they ever more than a concept for a future? We shall probably never know. ®

The author invites anyone with anecdotal or documentary evidence of these and/or other Sinclair "might have beens" to drop him a line.