This article is more than 1 year old

Meet the man building an AI that mimics our neocortex – and could kill off neural networks

Palm founder Jeff Hawkins on his life's work

How it works: Six easy pieces and the one true algorithm

Hawkins' work has "popularized the hypothesis that much of intelligence might be due to one learning algorithm," said Google's Professor Ng.

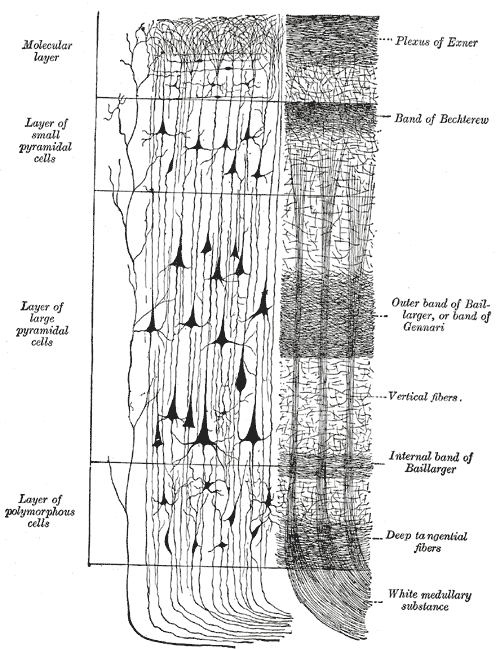

Part of why Hawkins' approach is so controversial is that rather than assembling a set of advanced software components for specific computing functions and lashing them together via ever more complex collections of software, Hawkins has dedicated his research to figuring out an implementation of a single, fundamental biological structure.

This approach stems from an observation that our brain doesn't appear to come preloaded with any specific instructions or routines, but rather is an architecture that is able to take in, process, and store an endless stream of information and develop higher-order understandings out of that.

The manifestation of Hawkins' approach is the Cortical Learning Algorithm, or CLA.

"People used to think the neocortex was divided into sensory regions and motor regions," he said. "We know now that is not true – the whole neocortex is sensory and motor."

Ultimately, the CLA will be a single system that involves both sensory processing and motor control – brain functions that Hawkins believes must be fused together to create the possibility of consciousness. For now, most work has been done on the sensory layer, though he has recently made some breakthroughs on the motor integration as well.

To build his Cortical Learning Algorithm system, Hawkins said, he has developed six principles that define a cortical-like processor. These traits are "online learning from streaming data", "hierarchy of memory regions", "sequence memory", "sparse distributed representations", "all regions are sensory and motor", and "attention".

These principles are based on his own study of the work being done by neuroscientists around the world.

Now, Hawkins says, Numenta is on the verge of a breakthrough that could see the small company birth a framework for building intelligent machines. And unlike the hysteria that greeted AI in the 1970s and 1980s as the defense industry pumped money into AI, this time may not be a false dawn.

"I am thrilled at the progress we're making," he told El Reg during a sunny afternoon at Numenta's whiteboard-crammed offices in Redwood City, California. "It's accelerating. These things are compounding, and it feels like these things are all coming together very rapidly."

The approach Numenta has been developing is producing better and better results, he said, and the CLA is gaining broader capabilities. In the past months, Hawkins has gone through a period of fecund creativity, and has solved one of the main problems that have bedeviled his system – temporal pooling, or (to put it very simply) the grouping together of coincidences to understand a pattern of input from the world. He sees 2014 as a critical year for the company.

He is confident that he has bet correctly – but it's been a hard road to get here.

That long, hard road

Hawkins' interest in the brain dates back to his childhood, as does his frustration with how it is studied.

Growing up, Hawkins spent time with his father in an old shipyard on the north shore of Long Island, inventing all manner of boats with his father, an inventor with the enthusiasm for creativity of a Dr Seuss character. In high school, the young Hawkins developed an interest in biophysics and, as he recounts in his book On Intelligence, tried to find out more about the brain at a local library.

"My search for a satisfying brain book turned up empty. I came to realize that no one had any idea how the brain actually worked. There weren't even any bad or unproven theories; there simply were none," he wrote.

This realization sparked a lifelong passion to try to understand the grand, intricate system that makes people who they are, and to eventually model the brain and create machines built in the same manner.

Hawkins graduated from Cornell in 1979 with a Bachelor of Science in Electronic Engineering. After a stint at Intel, he applied to MIT to study artificial intelligence, but had his application rejected because he wanted to understand how brains work, rather than build artificial intelligence. After this he worked at laptop startup GRiD Systems, but during this time he couldn't get his curiosity about the brain and intelligent machines out of his head – so he did a correspondence course in physiology and ultimately applied to and was accepted in the biophysics program at the University of California, Berkeley.

When Hawkins started at Berkeley in 1986, his ambition to study a theory of the brain collided with the university administration, which disagreed with his direction of study. Though Berkeley was not able to give him a course of study, Hawkins spent almost two years ensconced in the school's many libraries reading as much of the literature available on neuroscience as possible.

This deep immersion in neuroscience became the lens through which Hawkins viewed the world, with his later business accomplishments – Palm, Handspring – all leading to valuable insights on how the brain works and why the brain behaves as it does.

The way Hawkins recounts his past makes it seem as if the creation of a billion-dollar business in Palm, and arguably the prototype of the modern smartphone in Handspring, was a footnote along his journey to understand the brain.

This makes more sense when viewed against what he did in 2002, when he founded the Redwood Neuroscience Institute (now a part of the University of California at Berkeley and an epicenter of cutting-edge neuroscience research in its own right), and in 2005 founded Numenta with Palm/Handspring collaborator Donna Dubinsky and cofounder Dileep George.

These decades gave Hawkins the business acumen, money, and perspective needed to make a go at crafting his foundation for machine intelligence.

The controversy

His media-savvy, confident approach appears to have stirred up some ill feeling among other academics who point out, correctly, that Hawkins hasn't published widely, nor has he invented many ideas on his own.

Numenta has also had troubles, partly due to Hawkins' idiosyncratic view on how the brain works.

In 2010, for example, Numenta cofounder Dileep George left to found his own company, Vicarious, to pick some of the more low-hanging fruit in the promising field of AI. From what we understand, this amicable separation stemmed from a difference of opinion between George and Hawkins, as George tended towards a more mathematical approach, and Hawkins to a more biological one.

Hawkins has also come in for a bit of a drubbing from the intelligentsia, with NYU psychology professor Gary Marcus dismissing Numenta's approach in a New Yorker article headlined Steamrolled by Big Data.

Other academics El Reg interviewed for this article did not want to be quoted, as they felt Hawkins' lack of peer-reviewed papers combined with his entrepreneurial persona reduced the credibility of his entire approach.

Hawkins brushes off these criticisms and believes they come down to a difference of opinion between him and the AI intelligentsia.

"These are complex biological systems that were not designed by mathematical principles [that are] very difficult to formalize completely," he told us.

"This reminds me a bit of the beginning of the computer era," he said. "If you go back to the 1930s and early 1940s, when people first started thinking about computers they were really interested in whether an algorithm would complete, and they were looking for mathematical completeness, a mathematical proof. If you today build a computer, no one sits around saying 'let's look at the mathematical formalism of this computer.' It reminds me a little about that. We still have people saying 'You don't have enough math here!' There's some people that just don't like that."

Hawkins' confidence stems from the way Numenta has built its technology, which far from merely taking inspiration from the brain – as many other startups claim to do – is actively built as a digital implementation of everything Hawkins has learned about how the dense, napkin-sized sheet of cells that is our neocortex works.

"I know of no other cortical theories or models that incorporate any of the following: active dendrites, differences between proximal and distal dendrites, synapse growth and decay, potential synapses, dendrite growth, depolarization as a mode of prediction, mini-columns, multiple types of inhibition and their corresponding inhibitory neurons, etcetera. The new temporal pooling mechanism we are working on requires metabotropic receptors in the locations they are, and are not, found. Again, I don't know of any theories that have been reduced to practice that incorporate any, let alone all of these concepts," he wrote in a post to the discussion mailing list for NuPic, an open source implementation of Numenta's CLA, in February.