This article is more than 1 year old

Government report: average Oz user will want 15 Mbps by 2023

Looking behind the Vertigan report

Updated with reply from Communications Chambers With the launch of the report, communications minister Malcolm Turnbull seems to have taken a more generous view of the predictability of the future.

In April 2013, Turnbull scorned predictions five to ten years in the future were uncertain, adding that he was ““knowledgeable enough and modest enough to know that you can't predict the future with great certainty”.

The Vertigan panel's report, which says the best decision would be to do nothing and leave broadband to the market, and that FTTP is $AU16 billion more expensive than the government's multi-technology model, is an evaluation not over five or ten years, but out to 2040, and includes a bandwidth demand forecast for the Australian household of 2023.

The minister has, unsurprisingly, welcomed the report, since it supports both the key characteristics of his preferred multi-technology model, that it's cheaper and should be rolled out faster than the former government's fibre-to-the-premises model.

One part of the Vertigan review - that rural subsidies cost $AU7,000 per premises connected over and above net benefits - have been waved aside, with Turnbull maintaining the government's commitment to wireless and satellite rollouts in the NBN.

Selling slower services

The unpalatable part of the whole thing is the same as it has always been: the government is essentially deciding policy on the basis that "you don't need 100 Mbps", which echoes Tony Abbot's 2013 claim that 25 Mbps is enough for most people.

The Communication Chambers bandwidth forecast claims such accuracy that it can even predict what Australian households will use in their most intensive four minutes of each month in 2023.

Since the bandwidth forecast, made by UK-based Communications Chambers, is one of the cornerstones of the review, it deserves a closer look.

Key assumptions

The first problem Vulture South has with the Communications Chambers report is its handling of the question of peaks.

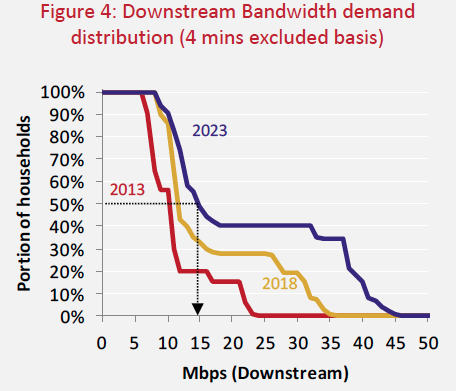

The report offers a median download requirement of 15 Mbps for Australians by 2023, something which seems nearly-obsolete even today. Let's take a look at the chart:

Communication Chambers' median bandwidth forecast

Over the next eight years, the report says, the median household bandwidth demand will rise by less than 50 per cent – a CAGR of just 4.14 per cent.

That represents a significant slowdown in bandwidth demand growth. The Cisco Visual Network Index prediction for just half of the same period – 2013 to 2018 – is for consumer, fixed-line Internet bandwidth consumption to grow at a CAGR of 30 per cent.

Predictions can be discounted – the report specifically dismisses the VNI because it doesn't talk about the edge of the network – but history tells us that consumer-level consumption is rising at more than double the VNI prediction. The ABS records of download volumes show that from 2009 to 2013, CAGR ran at more than 64 per cent.

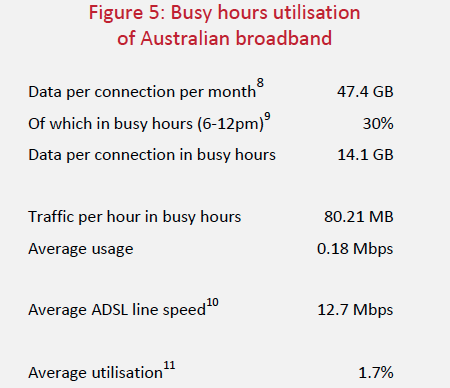

The report correctly assesses that access network utilisation at peak periods is just 1.7 per cent of its total capacity. This, however, is completely un-testable:

Communication Chambers' access network utilisation calculation

The other howler in this assumption – one that will fuel accusations that the whole Vertigan process represents a political report to serve a political end – is that Australia's average ADSL line speed is above 12 Mbps, citing the government's MyBroadband data cube as its source.

There's no such data in the MyBroadband cube. It provides median performance for each distribution area (even the average of the medians, a plainly silly measure, doesn't line up with the report's average of 12.7 Mbps).

The other issue with this as the basis of policy is that it ignores the huge variation from bottom to top: 25 per cent of the areas recorded in the dataset report median speeds below 7.13 Mbps, and there are more than 2,200 distribution areas that recorded medians below 2.5 Mbps.

Take cloud backup, which the report lists as a secondary application: it's the prime example of the kind of application whose utility and value to end users is closely aligned to the speed the end user can achieve.

Even at 15 Mbps - and assuming that speeds were symmetric, which they won't be - cloud backup of a 500 GB MacBook Air is a nine-hour process that would exclude any other application; at 2.5 Mbps it's simply not feasible (more than 55 hours).

The report assumes that the kind of burst capacity that the NBN would provide over fibre has no utility to end users – and that assumes the one thing that Turnbull denied in 2013: that the future can be predicted with sufficient certainty to define a fine-grained bandwidth requirement nine years hence.

Usage != Demand

In gauging demand as a proportion of a contrived “access network capacity” number, the report assumes that user behaviour is solely a reflection of the services they want to buy.

This isn't true: Australian fixed-line broadband user behaviour is constrained by the cost structure of the industry, leading to the imposition of download caps. As a network engineer said to The Register: “With the cap, virtually all of the actual utilisation numbers you can dream up are artificially constrained.”

And why the caps? Because ISPs have to buy transit to the Internet from a relatively small pool of providers, and they want to minimise their costs. “In the absence of those charges, the pressure on ISPs to constrain utilisation would largely evaporate, and usage would consequently increase far in excess of Vertigan’s estimates,” the engineer said. ®

Bootnote: The original version of this article, talking about cloud backups, failed to note that our figures make the optimistic assumption that speeds are symmetric.

Right of Reply

Robert Kenny, founder of consultancy Communications Chambers, which the Vertigan panel engaged to develop its future broadband consumption models, feels our story is not fair.

Here's his response to our story:

In its article about Communications Chambers’ broadband demand forecast for the Vertigan Panel, The Register accuses us of various howlers. The good news for Australian policy making is that these accusations are completely false.

There is too much in The Register’s article which is wrong to address every point, so I’ll primarily focus on one key error. Richard Chirgwin wrote:

“Over the next eight years, the [Communications Chambers] report says, the median household bandwidth demand will rise by less than 50 per cent – a CAGR of just 4.14 per cent.

That represents a significant slowdown in bandwidth demand growth. The Cisco Visual Network Index prediction for just half of the same period – 2013 to 2018 – is for consumer, fixed-line Internet bandwidth consumption to grow at a CAGR of 30 per cent.”

It’s hard to know where to begin with this. The Register is confusing our metric (a per household median peak bandwidth requirement) to Cisco’s (a national total traffic requirement). This isn’t just apples and oranges - it’s apples and orangutans.

There is simply no reason to expect these two to line up, and to suggest that we must be forecasting a slowdown is simply daft. In fact, the traffic implied by our forecasts is actually appreciable higher than Cisco’s.

Traffic can grow dramatically even if required peak bandwidth does not. The reason is simple - imagine a one person household whose peak bandwidth is set by (say) occasional HD TV viewing. If this person doubles their consumption of HD TV, the traffic they use increases dramatically, but the peak bandwidth required need not change at all.

Mr Chirgwin also accuses us of getting current available bandwidth wrong. I disagree, but the key point is that this figure has literally no impact on our forecasts - it’s not an input to our model, because we wanted to reflect ‘unconstrained’ demand - that is, demand not limited by available bandwidth.

And Mr Chirgwin worries that usage in the model is constrained by download caps, driven by transit costs. It isn’t clear why he thinks transit costs are about to go away, but again he is missing the bigger picture. The model already assumes that in 2023 the average adult will (just at home) consume 1.9 hours per day of online video services and use the web for 2.0 hours daily - and some users will do much more than this. This is certainly not a world where users are scared of data caps - and even if you assumed even higher levels of usage than this, it doesn’t make much difference to required bandwidth, for the reasons set out above.

Our model is surely not perfect. But it is time for the debate to move on from ‘there’s going to be lots more traffic, so we’ll need lots more bandwidth’ - the reality is a good deal more complicated than that.

®