This article is more than 1 year old

Spies would need superpowers to tap undersea cables

Why mess with armoured 10kV cables when land-based, and legal, snoop tools are easier?

The Register has found itself subject to a certain amount of criticism for this author's scepticism regarding whether the NSA has been snooping on optical fibre cables by cutting them.

Glenn Greenwald's recent “NSA cut New Zealand's cables” story is illustrative of credibility problems that surround the ongoing Edward Snowden leak stories: everybody is too willing to accept that “if it's classified, it must be because it's true”, and along the way, attribute super-powers to spy agencies.

In running the line that undersea cables were cut, Greenwald is straying far enough from what's feasible and credible that his judgement on other claims needs to be questioned.

It seems to The Register almost certain that neither Glenn Greenwald nor Edward Snowden have actually held a submarine fibre cable in their hands.

If all you think of is the fibre itself, it probably seems trivial: dive down, snip the fibre, put in a splitter, let people scratch their heads about a ten-minute outage, what's the problem?

The fibre is the easy part.

Image: Kokusai Cable Ship Ltd

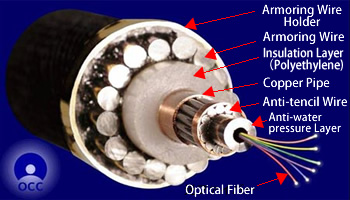

To get into the fibre is far beyond trivial. You have to remove a metre or so of sheath, then the steel armour – 16 or so wires of quarter-inch steel – then a hard poly layer, a copper pipe, and yet more steel wire before you get to the fibres.

Once you've cut off all the stuff protecting the fibre, you're not cutting one bit of glass. It's more typical for each cable to have six pairs – twelve individual fibres – each of which (in the case of Southern Cross, which Greenwald singled out) is carrying hundreds of megabits per second.

Some of those hundreds of megabits per second of traffic will still get through, because some of Southern Cross' customers will be buying “protected” traffic, so in the event of a failure on one route, their communications go over the other route.

Others, with shallower pockets and an eye to the long-term reliability of submarine cables, won't have bothered. The instant you cut the fibre, it won't just be Southern Cross that notices, because dozens of unprotected customers will also be yelling at them (not to mention all routes that suddenly become unreachable on the BGP table).

10kV of 'ouch'

But you won't get as far as cutting the fibres, because on the way into the cable you will have had to cut into a chunk of metal that's carrying power to the repeaters all the way along the cable. At the head end of the cable, it's fed by kit like this Alca-Lu box, at 10 kV dc or more.

So when our hypothetical diver gets through the steel and plastic, and before he gets to the fibre, two things will happen: the whole cable will go dark because the power to the repeaters disappeared, and the diver will be near a kilovolt discharge to earth via seawater.

“We've got rubber, the diver will be okay”. Yeah, right.

You have to do that without even knowing exactly where the fibre is. Yes, there are maps, and if you were in spooksville you can get your hands on the GPS that tells you where the cable-laying ship was within a few metres.

And the fibre is down on the sea bed below the ship; some drift is inevitable in the laying operation, and when it's close to the shore, the fibre is buried using robot ploughs - at depths up to three metres.

Cable plough

Image: Kokusai Cable Ship Ltd

So the plot to tap the optical fibre doesn't involve a quick dip with scissors; it starts with a long project to locate and dig out the fibre (one reason why a fibre break takes a while to fix, even for the owner who knows where it should be).

Fibre splicing

If you haven't been paying attention to debate around Australia's National Broadband Network (NBN), you don't know that fibre splicing is a fairly exacting operation.

Sure, it's gone a long way since the late 1980s when every bit of the operation had to happen by hand, but the operation remains the same: perfectly polish the bits of fibre that have to be spliced, perfectly align them, and get them sealed.

Splices don't even like dust, let alone seawater.

What about repeaters?

Surely, then, there's a spot where it's safer and easier to tap the signals: the repeaters?

The problem is for any practical operation, there aren't so many repeaters that are reachable in a way that humans can deal with the fibre. The minimum repeater spacing on Southern Cross is 45 km; at each end of the cable, there's only one or two that are practical to reach.

By the time you're at the third repeater or so, the cable will typically be far too deep to be easily accessed.

Submarines

The “NSA cut the cables” story is older than we think: in fact, it's been around since at least 2001, when ZDNet carried this piece.

It makes an interesting point: if you have a submarine with a cable jointing room, say the USS Jimmy Carter (says the story), then you'd have an environment that could work on cables. Moreover, if you went for the deepwater-style cable with less armour, that's also not buried but laid on the sea floor, it wouldn't be hard to find.

The only problem is that the old ZDNet piece fails to connect the submarine specs with the cable specs. According to this entry in Naval Technology, Seawolf-class subs have a dive depth of 610 metres; while this item at Cryptome.org gives the dive at a more conservative 800 feet.

At 600 metres, the submarine typically wouldn't be dealing with the light cables: heavy armour is recommended for use down to 1,000 metres.

And all the problems of outages – cut the cable, send the world mad – and handling kilovolt power still remain.

Finally, we would remark that cutting a fibre is an awful lot of effort to go to when:

- Providers have to comply with lawful intercept requests;

- An unknown amount of traffic will be encrypted – not just by the end user, but by the carrier; and

- Even if you need your operation to be covert – that is, secret even from the submarine cable owner – it's far easier to work on land than under the ocean.

It is also worth considering that a document can be classified for no other reason than it was authored by someone within the NSA. The internal documents might be aspirational (a bid for budget to try something), self-aggrandising (exaggerating capabilities to get employment), blue-sky, or even a misdirection.

Assuming that all leaked documents is a revelation is therefore dangerous. And treating every spy and spook as some kind of superhero is a dangerous distraction from their real capabilities and their everyday activities, and the invasions of privacy we can demonstrate and act upon. ®