This article is more than 1 year old

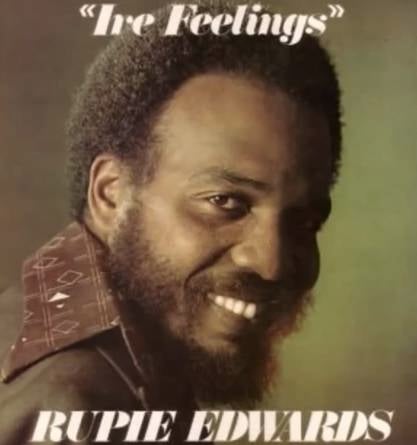

Dub pioneer Rupie Edwards' Ire Feelings – 40 years on

Fusing culture and tech together with echoing reggae sound

Trackback Phil Strongman reveals the bizarre true story of how the first real musical fusion of technology and culture ended up coming from the Third World.

In late 1974, out of nowhere, the first dub hit anywhere in the world leapt into the UK Top Ten.

Upon its release that autumn, Rupie Edwards’ innovatory Ire Feelings had received virtually no airtime on London's Capital Radio and even less on BBC Radio One – the country’s biggest stations – but the demand from kids in discos and clubs made the haunting, echoing reggae 45 into a massive hit.

And it wasn’t just a "new" artist they were hearing – Edwards, a Jamaican, had never been anywhere near the British charts before – but an entire new genre, perhaps the first that genuinely fused both modern culture and the latest technology.

"I’d actually booked the studio that day to record Shorty The President," says Edwards now, "and Shorty was late and I had this song in my head to do. So I dropped it. 'Feeling High' – and trust me, I was – and Errol Thompson, the mixer from Studio One was then working for me. And we had this big copper pipe I’d dragged in off the street and I whacked it, recorded it, just for the sound. And Errol said 'I like working with you, you’re always trying new things'.

"So we recorded the song and the next day we mixed it and at one point Errol said, 'Hang on, it’s different, it’s changed, we should start again'. And I said 'no, no', ‘cos I knew that if we started mixing again we’d never get it back. So we finished it and Pat Kelly mastered it, then I left a copy with my partner in the shop I had on West Parade, downtown Kingston. And she rang me that same evening saying, 'Every time I play it the street block up!'”

Within weeks, those crowds on the streets were buying up copies of Ire Feelings, which became a best-selling Jamaican hit and Edwards had started the journey that would lead to the British charts.

Dub, similarly, was swiftly picked up by the early punk bands – noticeably The Clash and then the poppier Police. And, right up to the present day, dub remains a method that still has great influence with everyone from Krewella to the Imagine Dragons and Justin Bieber.

We had this big copper pipe I’d dragged in off the street and I whacked it, recorded it, just for the sound.

Of course, popular music had always utilised the latest tech gadgets and effects but the 3- and 4-track recorders that had captured some of the rock’n’roll of the late 1950s were still in use in 1967 when much of the defining sound of the Sixties was captured; Jimi Hendrix, The Who, The Byrds, The Doors, The Kinks and The Beatles all recorded on decks with barely a handful of channels. Much of Sergeant Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band was famously cut on a 4-track.

And, from ’67 on, a whole herd of "hairy" prog bands used an array of the new moog synths and mellotrons in their work. But these instruments were usually just replacing, or emulating, the role of Hammond organ, piano or electric guitar.

By the start of the '70s, there were 8- and 16-track decks across the UK and US, as well as some that could potentially take 24 channels and proto-types that promised even more.

There was also a flood of new studio hardware – echo machines, reverbs, compressors and tape delays. Which meant that older outboard, as well as 8 track decks, began to trickle down to Third World studios including those in Jamaica where producers such as Lee "Scratch" Perry, King Tubby, Bunny "Striker" Lee and Rupie Edwards began to use the recording console, not as a mere pathway, but as an instrument in itself – adding sound effects, boosting rhythm sections, throwing in lines or melodies from other recordings and dropping vocals in and out, while inserting rhythmic layers of echo, reverb or delay to them.

Every time I play Ire Feelings the street block up!

Such experiments had been going on there since the late '60s – partly because it was economical, a way of re-using backing tracks – but the real flowering of dub occurred in the early '70s. And its first chart star was Rupie Edwards, a reggae veteran who’d been singing and recording since late 1962.

Ultimately, Edwards’ pioneering role in dub was not that well rewarded.

That’s the wickedest part about it … I’ve not really been paid for the work … Cos I got a call in Jamaica from the late Tony Cousins [of Creole Music], saying, "Come on over, come and do Top of The Pops etc …" I flew over here in 1974 and Tony and Bruce White met me at the airport with a contract in their hands. I signed.

I trusted Tony and I was glad just to be there – because, in those days, to be in the British Top Ten hit [parade] was everything – almost every country in the world wanted to licence that material once you were in the UK Top Ten.

After I’d signed, all the new copies of the single just had Creole Music printed there but the original pressings of the single had had MCPS on it … [the MCPS – now the MCPS-PRS – being the Mechanical Copy Protection Society, an organisation dedicated to making sure artists get paid every time their tracks are aired on TV, local and national radio etc.]

And despite the chart success of Ire Feelings, and its more prosaic follow-up Leggo Skanga, Radio One still refused to give him much airtime.

"John Peel and Emperor Rosko were the only [radio] DJs that would play it much. Radio One wouldn’t playlist it," Edwards' tells us.

It was a decision which, he says, "cost me over £30,000 in PRS payments" – over one quarter of a million pounds in today’s money.

These days, Rupie Edwards continues to run a small record shop in Ridley Road Market, Dalston, London – like the one he had in Kingston near Bob Marley’s music stall – where the trailblazer still plays reggae tunes to a passing crowd of local housewives, older Jamaicans and some blissfully unaware hipsters. ®