This article is more than 1 year old

Ground control to 2014: A year in Space

Four-legged landings and history-making comet-chasers

Review of 2014 The year 2014 belonged, without question, to the comet-chasing Rosetta mission, which moved humanity’s space exploration programme forward by landing on a moving space rock out in the depths of the cosmos for the first time ever.

The first step in the epic journey this year was accomplished in January, when boffins at the European Space Agency managed to awaken the probe from its three year slumber.

"We got it!" roared Rosetta project scientist Matt Taylor, punching the air with glee on the ESA's live feed of the event. "I can speak on behalf of everyone in saying that that was rather stressful," he added, with a bit more reserve.

"Now it's up to us to do everything that we've promised we can do. The work begins now, and it looks like it's going to be a very fun-filled next two years."

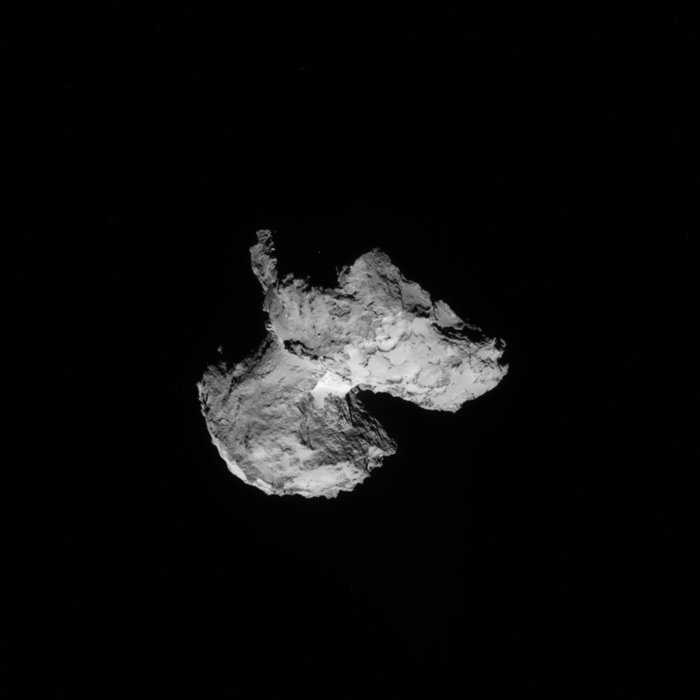

A couple of months later, the Rosetta spacecraft sent back the first images of the comet it had been chasing for 10 years and nearly 800 million kilometres – 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

Those first pics were just a speck in an ocean of specks five million kilometres away from the spacecraft, but soon, we would all become familiar with the duck-shaped rock 524 million kilometres from the Sun.

As Rosetta crept closer, it started to find out more and more about its comet target. The probe found that 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko was sweating the equivalent of “two small glasses of water into space every second”.

The craft also discovered that the space rock wasn’t as icy as some of the scientists were expecting. Within 5,000km of the comet, Rosetta could tell that it was at a relatively balmy -70 degrees Celsius, 20 or 30 degrees warmer than the boffins thought it would be.

Comet 67P/Churyumov Gerasimenko. Credit: NASA

But all that was just to whet the appetite as ESA prepped Rosetta to become the first space probe to drop into orbit around a comet. To get there, the craft needed to complete a six and a half minute burn to insert into a looping orbit. It was a task that sounded pretty simple, but needed orbital mechanics that took years to formulate and massive amounts of computer processing to check.

Then, in August this year, Rosetta became the first manmade craft to successfully chase down a comet.

“After 10 years, five months and four days travelling towards our destination, looping around the Sun five times and clocking up 6.4 billion kilometres, we are delighted to announce finally ‘we are here’,” says Jean-Jacques Dordain, ESA’s Director General.

“Europe’s Rosetta is now the first spacecraft in history to rendezvous with a comet, a major highlight in exploring our origins. Discoveries can start.”

Once Rosetta had started circling its comet prey, the fun really began. The probe needed to perform triangular orbits to get even closer to the space rock, so it could nab scientific data like the mass of the 10 billion tonne comet and pick a landing spot for the Philae lander.

ESA eventually settled on a region known as Site J, which was at the top of the rock and measured about 4km across at its widest point. The agency was keen to stress that there was no perfect landing spot on the rocky, widely uneven surface of the comet, but the boffins fancied their chances with this spot.

Rosetta wasn't neglecting the science as it prepped for Philae's landing either, before the attempt there was just time to snap a selfie or two at the comet and figure out that 67P is trailing a horrific stench through space. According to Rosetta's Orbiter Sensor for Ion and Neutral Analysis (ROSINA), the comet has all the great chemicals for the pongiest smells - hydrogen sulphide, the odour of rotting eggs, whiffy ammonia and formaldehyde.