This article is more than 1 year old

Why is that idiot Osbo continuing with austerity when we know it doesn't work?

No one told us we could do that!

Look at Blighty in the '30s – we were just dandy!

The super-secret little clue is in something Wren Lewis said:

The models used by pretty well all central banks would therefore imply that temporary cuts in government spending were contractionary, absent any monetary policy offset.

“Absent monetary policy offset” is really a rather strong qualification there. For, as I pointed out last week, we are pretty sure that the unconventional monetary policy of the past few years has worked.

For, recall what the basic Keynesian contention is: monetary policy first, then we hit that zero lower bound for interest rates and we can do no more monetary policy. Therefore we've got to turn on the spending taps (or at least not close them off) as fiscal policy is the only thing we've got that works.

But our recent experience is that this isn't in fact true.

We have monetary policy that works at the zero lower bound. Of course, that's something that we've only just found out. Or so the conventional (read: Keynesian) wisdom has it. But that's not really true, for we tested this model in the UK in the 1930s, and it worked.

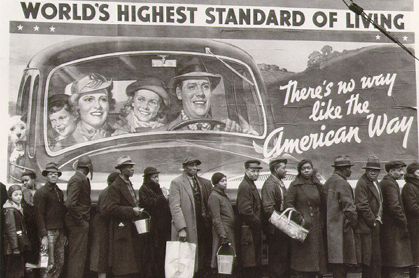

The experience of the UK in that Depression was very different indeed from that of the US. Our really horrible economic problems were in the 1920s, by the early '30s we were doing OK. Not great, but OK. Then along comes that Great Depression and of course we're not doing so OK again.

So, what did the government do?

Well, actually, there's a startling number of coincidences here. The National Government (including Ramsay MacDonald and the first experience in government of the Labour Party) got turfed out in favour of the Tories, who then proceeded to cut spending.

Sure, it wasn't really vicious cutting: total spending went from £1.4bn to £1.32bn the next year, for example. But this is real cuts in real budgets, not just a dialling back of former plans to expand it.

But the economy also boomed: by 1934 we were back above earlier GDP peaks and we continued to have good growth up to the war. In fact, we also had the largest house building boom in the history of the country, at least as far as the private sector was concerned.

In the absence of any serious planning controls 300,000 houses a year were being thrown up: we wouldn't mind having that today.

So, austerity leading to growth. But of course that's not the whole story: there's that monetary offset to consider. What the Conservative Party also did was come off the gold standard. Being on it meant that you didn't have any control over the exchange rate nor could you run an independent monetary policy. Dropping it meant you had some control over both.

So, off they came (and prompted the immortal line from a National Government Minister, lamenting that “No one told us we could do that!”), sterling fell 25 per cent in value, interest rates were lowered and we had exactly that monetary offset that allowed the austerity to also, at the very least, coincide with growth.

And what was done this time around?

Well, quantitative easing increased the money supply, the cut in interest rates meant that sterling fell around 25 per cent and we have indeed had economic growth, even while the government has been reasonably sober in its budgeting – if not practising full blown austerity.

As before, none of this means that fiscal stimulus wouldn't have worked better. I might not think it would, those who want a smaller state might not think it would, and it also doesn't mean that that “confidence” idea put forward as a reason for “expansionary austerity” has any value to it.

But it is a good example of what I regard as the flaw in that Keynesian case. Sure, if you've got no monetary policy left possible, than fiscal policy is all you've got. Or else you suffer the recession some more, of course.

That said, recent experience tells us that we've got a lot more monetary policy possible than we thought. And that experience of the 1930s also tells us that it does work.

Got a recession? Devaluation of sterling is monetary policy just as much as changing interest rates is. And we've robust evidence that it worked once and I would argue that the past few years have shown it working again.

It's still open to everyone to squabble over the idea that fiscal policy, turning on the spending taps, will work better. But it's not really viable to insist that it's the necessary response, the only one available to us.

Simply on the grounds that we've at least one historical instance of that not being the case. ®